Mapping Revolution, Mapping Slavery: Recent Work by Bertie Mandelblatt, George S. Parker II ’51 Curator of Maps and Prints

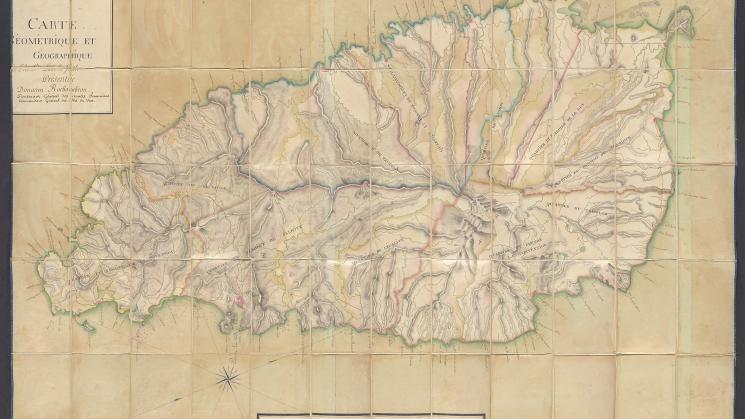

Above: Anonymous map from 1793 or 1794 labeled “Carte géométrique et géographique de l’isle Sainte Lucie la Fidèle, présentée à Donatien Rochambeau, Lieutenant Général des armées françaises, Commandant Général des Isles du Vent.”

Earlier this year, George S. Parker II ’51 Curator of Maps and Prints Bertie Mandelblatt presented a paper at the Warburg Institute’s Maps and Society Lecture titled “Mapping Revolution, Mapping Slavery: the Vicomte de Rochambeau and Cartographic Dreams of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity in the Caribbean.” In it, Bertie traces the practice of renaming locations in France’s imperial possessions in the Caribbean based on the utopian ideals of the French Revolution.

The piece is based on an anonymous hand-drawn map acquired by the John Carter Brown Library in 2022 that was part of the collection of Donatien Rochambeau, a prominent French military officer and revolutionary figure of the decades before and immediately after the turn of the 19th century. The map is exquisitely detailed, with striking watercolor and pencil renderings of the island’s topography and a bright blue silk border.

For Bertie, the map offers evidence of a practice of importing the French Revolution to the island nation of Saint Lucia in the Lesser Antilles chain of islands in the Caribbean. On this map, each jurisdiction of Saint Lucia has been renamed to reflect the ideals of the French Revolution. They include such names as Quartier de l’Égalité, Quartier du Tricolor, and Quartier de L’Union, all references to ideals and symbols that evoked the triumph of the Revolution. These revolutionary toponyms have long since disappeared, but French names remain in use in Saint Lucia, a lasting testament to the decades, and indeed centuries, of French imperial occupation and claims to the island, contested by the British until the colony was definitively ceded to Great Britain in 1814.

As she explains in her paper, “This map of Saint Lucia involved in myriad ways a panoply of political figures, events and ideas of the three so-called Atlantic Revolutions: the American Revolution commonly dated 1775 to 1783, the French Revolution that broke out 1789 and ended with the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire in 1799, and the Haitian Revolution that began in 1791 and ended in 1804. The map captures in unique manuscript form a short-lived moment in the revolutionary history of mapping imperial possession in the overseas French empire.”

Bertie plans to publish the paper that she presented in March as an article in the coming months. We look forward to reading it and to providing the link to interested community members as soon as it is available. After all, her work points to key processes and practices that we are still exploring and, importantly, questioning today. As she explains at the end of her paper, “Rochambeau’s map of Saint Lucia is an artifact that proclaims St. Lucia’s loyalty to a radical new order that reconceived the land itself in terms of the revolutionary concepts of liberty and equality, yet was still rooted in the institution of transatlantic slavery.”