With the Spanish invasion of Mesoamerica in the sixteenth century, indigenous societies experienced profound upheavals that permeated all facets of life. Indigenous modes of recording information and recounting the past, including pictorial traditions, oral discourses, and embodied practices were transformed under Spanish rule by the introduction of alphabetic script, giving rise to distinct forms of expression. Sometimes working in conjunction with missionaries, and other times working independently, indigenous artists and scribes drew upon pre-Columbian, colonial, and European traditions— inventing new modes of documentation in which both image and text functioned to reclaim ownership of contested territories, preserve personal lineages and collective histories, and maintain indigenous ways of life.

Curated by the students of HIAA 1151: Painting Indigenous Histories in Colonial Mexico, a course taught by Mellon Postdoctoral Research Associate (and former JCB fellow) Jessica Stair, the following exhibition centers around six colonial-era indigenous manuscripts from the John Carter Brown Library’s collection, whose dates of creation range from the sixteenth through the eighteenth century. These documents engage four key themes: The Political Force of Images, an analysis of the multifaceted uses of text and images to assert political authority in the Boban Calendar Wheel; Friars Interpret Indigenous Pasts, which considers orality, image, and text in friar Juan de Tovar’s codex; Proselytizing with Image and Text, which features three pictorial catechisms and narrates the use of pictorial and alphabetic writing in Spanish and indigenous Catholicisms; and Preserving Property and Primordial Pasts, which examines the strategic revival of iconographic conventions and materials of the pre-Columbian past in the Codex Coyoacán. Together, these themes illuminate the evolution of indigenous pictorial and scribal traditions in colonial Mexico and provide a glimpse into the complex dynamics of indigenous life under Spanish rule, where pictorial manuscripts functioned as resilient sites of negotiation, contestation, preservation, and innovation.

The Political Force of Images

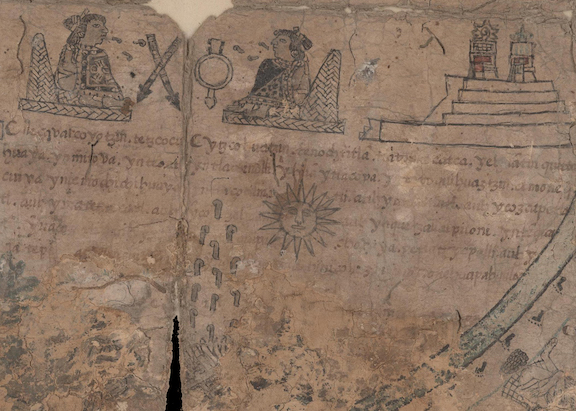

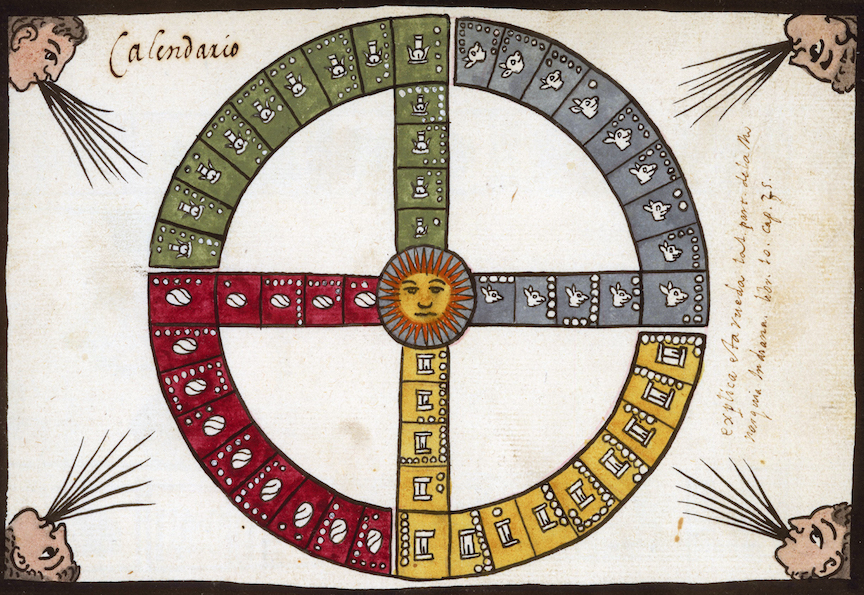

The Boban Calendar Wheel is an early colonial manuscript that likely played a role in bolstering the political and authoritative claims of an indigenous leader of Texcoco during the first decades of Spanish colonial rule. Historian Patricia Lopes Don has shed light on the historical circumstances under which the manuscript was likely made, suggesting that it was produced between 1545–46 and featured in the legal battle that occurred over the lands of the deceased ruler of Texcoco, don Carlos Ometochtli.1 Texcocan leader don Antonio Pimentel Tlahuitoltzin sought to use the manuscript, among others, to bolster his claim to royal lineage and property.2 The manuscript served both an administrative and cultural purpose, acting as a court document that functioned as a cultural intermediary between the indigenous leaders of Texcoco and the new colonial administrative architecture. The manuscript illustrates a marriage between colonial and indigenous cultural forms, featuring indigenous iconography that centers time, genealogy, and space to serve multiple functions in a culturally ambiguous milieu. By carefully utilizing image and text, the Boban Calendar Wheel tapped into multiple significations for both Spanish and indigenous readers, alike. This multifaceted object, which has received relatively little scholarly attention, presents an early perspective on colonial Mexico that allows contemporary scholars and interested readers to glimpse into the reality of law and life for indigenous colonial subjects.

Presented by Andres O’Sullivan-Comparan.

Actors and Purpose

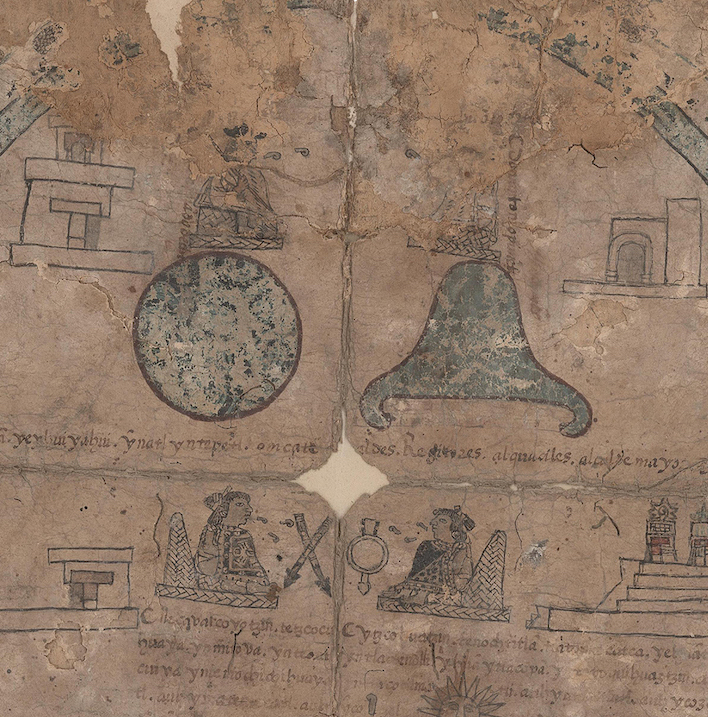

The Boban Calendar Wheel focuses mainly on dynastic claims made by don Antonio Pimentel Tlahuitoltzin during the aftermath of the death of Texcocan ruler don Carlos Ometochtli.3 Don Antonio appears prominently in the document, as the top right figure of the four that are currently visible in the manuscript. He sits to the right of don Hernando de Chávez, another indigenous leader from Texcoco and the “half brother of both [d]on Carlos and [d]on Antonio.”4 Their placement in close proximity to each other and the other figures on the page is indicative of the close relationship and importance that the creators of the manuscript were attempting to signify about the two, as they were the primary figures vying for power in the legal case. They appear in the top center of the manuscript.

The Boban Calendar Wheel focuses mainly on dynastic claims made by don Antonio Pimentel Tlahuitoltzin during the aftermath of the death of Texcocan ruler don Carlos Ometochtli.3 Don Antonio appears prominently in the document, as the top right figure of the four that are currently visible in the manuscript. He sits to the right of don Hernando de Chávez, another indigenous leader from Texcoco and the “half brother of both [d]on Carlos and [d]on Antonio.”4 Their placement in close proximity to each other and the other figures on the page is indicative of the close relationship and importance that the creators of the manuscript were attempting to signify about the two, as they were the primary figures vying for power in the legal case. They appear in the top center of the manuscript.

Directly beneath them, two additional figures are pictured, each sitting on an icpalli, a woven reed throne. These figures are Nezahualcoyotl and Itzcoatl, two leaders of the Triple Alliance, a pact between the most powerful city-states in the Basin of Mexico before the Spanish invasion. At the bottom of the manuscript, two additional figures who are no longer visible due to deterioration are depicted, representing Chichimec ancestors. Their symmetrical alignment and adjacency to don Hernando and don Antonio at the top of the manuscript visually insinuates a longstanding connection between these two indigenous leaders and the most powerful dynastic rulers of Central Mexican history.

Iconographic versus Textual Representations

Because the Boban Calendar Wheel was likely utilized by indigenous leaders in a colonial Spanish legal context, the manuscript had to appeal to both colonizers and the indigenous peoples they were representing. The Nahuatl text, as well as indigenous iconography that can be found in the manuscript demonstrate this point. Apart from the six main actors, two turquoise pictorial forms are featured prominently in the manuscript, just below don Antonio and don Hernando at the top. The images of a large circle and hill form are pictographic symbols representing water and a mountain referencing the concept of “in atl in tepetl” or altepetl, which is meant to signify the sovereignty of the city-state of Texcoco.5

Because the Boban Calendar Wheel was likely utilized by indigenous leaders in a colonial Spanish legal context, the manuscript had to appeal to both colonizers and the indigenous peoples they were representing. The Nahuatl text, as well as indigenous iconography that can be found in the manuscript demonstrate this point. Apart from the six main actors, two turquoise pictorial forms are featured prominently in the manuscript, just below don Antonio and don Hernando at the top. The images of a large circle and hill form are pictographic symbols representing water and a mountain referencing the concept of “in atl in tepetl” or altepetl, which is meant to signify the sovereignty of the city-state of Texcoco.5

In contrast to these indigenous iconographic forms is a large section of Nahuatl text, written below Nezahualcoyotl and Itzcoatl that highlights the military prestige and luster of the leaders of the Triple Alliance and lists the tributes they collected while campaigning. These two examples illustrate the different ways the Boban Calendar Wheel demonstrated the power of don Antonio in the context of a colonial environment, both pictorially and textually, through an indigenous lens as well as one that a Spanish colonial court would be able to understand.

In contrast to these indigenous iconographic forms is a large section of Nahuatl text, written below Nezahualcoyotl and Itzcoatl that highlights the military prestige and luster of the leaders of the Triple Alliance and lists the tributes they collected while campaigning. These two examples illustrate the different ways the Boban Calendar Wheel demonstrated the power of don Antonio in the context of a colonial environment, both pictorially and textually, through an indigenous lens as well as one that a Spanish colonial court would be able to understand.

Calendrical Continuity

The dynastic and political history in the center of the Boban Calendar Wheel is encircled by a representation of the Mexican solar calendar. The calendar is made up of eighteen veintenas, or periods of twenty days. Each veintena is illustrated by a picture, representing its name or aspects of associated ritual practices. For instance, on the upper left side of the circle, the veintena called Panquetzaliztli is represented with an image of a banner, pantli, and long, turquoise feathers, quetzalli, whose combined words make up part of the name. Every veintena is also labeled on the side with Nahuatl text that would have been recognizable to Spanish authorities through court translators. The manuscript’s circular design illustrates the continuity of Texcocan power over time. By framing the central argument in this legal battle with a circular and cyclical representation of time, the creators of the manuscript legitimize their claims by creating the perception that don Antonio can trace his noble lineage back to time immemorial.

The dynastic and political history in the center of the Boban Calendar Wheel is encircled by a representation of the Mexican solar calendar. The calendar is made up of eighteen veintenas, or periods of twenty days. Each veintena is illustrated by a picture, representing its name or aspects of associated ritual practices. For instance, on the upper left side of the circle, the veintena called Panquetzaliztli is represented with an image of a banner, pantli, and long, turquoise feathers, quetzalli, whose combined words make up part of the name. Every veintena is also labeled on the side with Nahuatl text that would have been recognizable to Spanish authorities through court translators. The manuscript’s circular design illustrates the continuity of Texcocan power over time. By framing the central argument in this legal battle with a circular and cyclical representation of time, the creators of the manuscript legitimize their claims by creating the perception that don Antonio can trace his noble lineage back to time immemorial.

Sources

Friars Interpret Indigenous Pasts

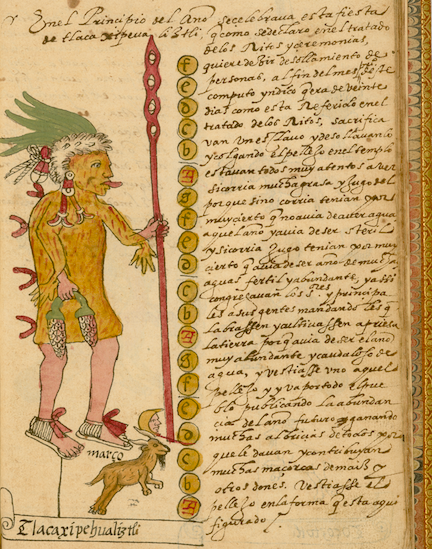

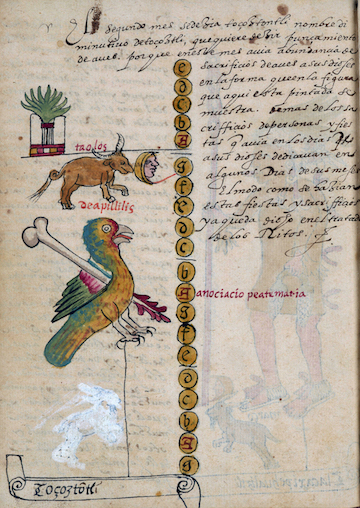

As part of their larger project of disseminating Catholicism and establishing colonialism in the Americas, friars sought to learn about various aspects of indigenous cultures and often collaborated with native artists to document indigenous histories. Jesuit Juan de Tovar, who was born in Mexico to Spanish parents, composed a manuscript known as the Tovar Codex, which provides a history of the Aztecs; a presentation of religious rites and ceremonies; and an explanation of the Mexican solar calendar in relation to the Christian calendar. The work was written in Spanish and later brought to Spain by Jesuit José de Acosta, with whom Tovar exchanged letters concerning his methods of collecting information about indigenous cultures. The first few pages of the manuscript include their correspondence, which describes how Tovar consulted the elders and lords of Mexico City, Texcoco, and Tula who orally recounted their histories from ancient pictorial manuscripts.

The Tovar Codex consists of three primary sections. The first, which is written in alphabetic script, relies heavily on the work of Dominican friar Diego de Durán and presents a history of the origins, rites and ceremonies of the Aztecs. The second section is composed of pictures relating to the preceding alphabetic section and also draws upon the work of Durán. The third portion was likely made in collaboration with an indigenous artist and overlays the Christian and Mexican calendars using both text and image. Unlike some of his Spanish contemporaries, Tovar trusted indigenous oral and pictorial modes of recounting the past, which, along with Durán’s textual history, contributed to the composition of his own history.

Presented collectively by members of the class.

Questioning Images and Orality

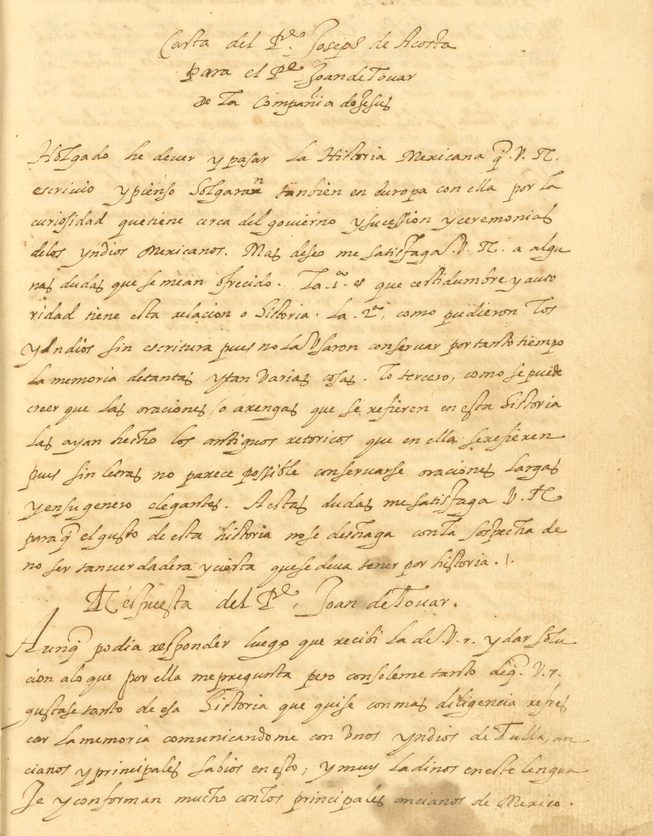

The Tovar codex begins with a written correspondence between Juan de Tovar, himself, and Spanish Jesuit José de Acosta. Their exchange provides great insight into the process of translation and consolidation of indigenous histories that informed Tovar’s work. Acosta expresses a number of concerns and questions about Tovar’s history inquiring as to the certainty and authority of indigenous modes of recounting the past, which draw not from a textual record, but from oral accounts and pictorial manuscripts. Acosta raises doubts as to the possibility of preserving such a detailed and lengthy history without the use of alphabetic script.

The Tovar codex begins with a written correspondence between Juan de Tovar, himself, and Spanish Jesuit José de Acosta. Their exchange provides great insight into the process of translation and consolidation of indigenous histories that informed Tovar’s work. Acosta expresses a number of concerns and questions about Tovar’s history inquiring as to the certainty and authority of indigenous modes of recounting the past, which draw not from a textual record, but from oral accounts and pictorial manuscripts. Acosta raises doubts as to the possibility of preserving such a detailed and lengthy history without the use of alphabetic script.

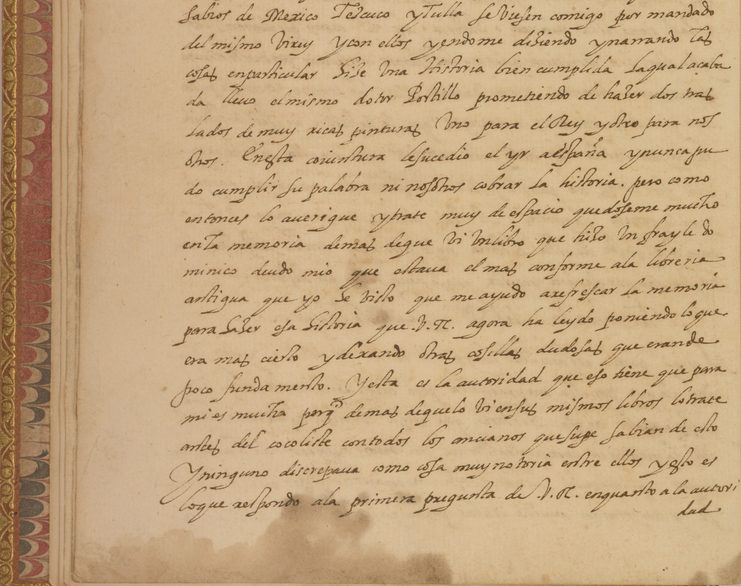

While Acosta’s misgivings shed light on the authority of the written word in Spanish culture, it is Tovar’s response that provides the greatest insight into the ways in which indigenous histories were preserved, relayed, corroborated, and eventually transcribed. In an effort to certify his own history, Tovar responds with a lengthy description of his process of acquiring information from knowledgeable elders and nobles from Mexico City, Texcoco, and Tula who consulted ancient pictorial manuscripts and recounted their histories with great precision.

Acknowledging the lack of an indigenous alphabetic history, Tovar details the other kinds of characters, hieroglyphics and calendrical forms that constituted the indigenous record—ones that he himself, admittedly, could not understand entirely. His complete history, then, considered a number of sources and intermediaries. First, Tovar drew from his own recollections of accounts that were elaborated and narrated to him by natives well-versed in their histories, who had consulted pictorial manuscripts. To substantiate and supplement these findings, Tovar then consulted the writings of Dominican friar Diego de Durán, relying heavily on Durán’s work to complete the first two sections of the Tovar Codex.

Recounting History with Both Text and Image

The Tovar Codex presents an Aztec history using multiple expressive forms that register the cultural convergence that Mexico was experiencing during the sixteenth century. Tovar relied on alphabetic script, indigenous pictorial forms, and a mixture of the two that are married in the later calendrical portions of the manuscript. The first two sections of the codex, which include both alphabetic and pictorial histories, drew upon friar Diego de Durán’s Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e islas de la tierra firme. This page from the textual history section of the codex describes the foundation of Tenochtitlan, which is referenced and pictured in the pictorial history section of the manuscript.

In the pictorial history section, Tovar illustrates a defining moment in the Aztec migration narrative: the founding of Tenochtitlan. The page features the iconic eagle standing on top of a nopal cactus growing from a stone in the middle of a lake that has become synonymous with Mexican identity. Yet, in this image the eagle is eating a bird as opposed to a serpent, which is most often depicted in the mythical foundation of Tenochtitlan. Footsteps leading up to the bottom of the nopal cactus specify the long migration these early settlers took to reach the site of what would become their capital city. Seated on either side of the cactus upon woven reed thrones are two Aztec rulers, whose names are indicated with the glyphs above them.

The rabbit glyph identifies the figure on the left at Tochtzin, and the glyph of a flowering nopal cactus and a stone indicates that the figure on the right is Tenoch. This iconography is supplemented above by a short text referencing the cactus, eagle, and the great lake of Tenochtitlan. The textual section of the manuscript briefly mentions the image in its narration of the event, but the image with its glyphic forms conveys meaning distinct from the text, further emphasizing the multifaceted communicative modes that Tovar relied upon to create his history of the Aztecs.

Merging Calendrical Systems

The Tovar Codex depicts three different kinds of calendars within the manuscript, but the most notable one appears in a section that combines the Julian calendar and the Aztec year count. The superimposition of the two calendars allows important dates to be easily convertible between the two systems, while allowing for Spanish friars to manifest their legitimacy through their own representation of time.

The Julian calendar divides the year into twelve months with a leap day every four years. Each day is given a name based on where it falls with the seven-day week. The Aztec year count divides the solar year into eighteen veintenas of twenty days each, plus five leftover days. In combining the two systems, the Tovar Calendar presents a page or two for each Aztec veintena, but labels each day with the European day name.

paper, Mexico. Digital version here.

The days are depicted as a chain going up the page, each day represented by one circle, and each group of five curiously divided with a small dash. Inscribed within each circle are the letters A through G, indicating the day of the Christian week. To the left of the days are images related to the Aztec veintena, with the name of the veintena written below it in alphabetic Nahuatl. Above the days and to the right of the chain is written information about the veintenas and associated festivities that occur with them, penned presumably by Juan de Tovar, who relied on Nahua informants for information about each veintena.

This page shows the twenty days of Toçoztontli, the second veintena in the Tovar Calendar. The Christian feast day of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary occurs on the ninth day, indicated in red by a gloss next to a letter “A.” The symbol for this veintena, a bird pierced with a bone object, appears to the left of the day count.

Compiling Histories

Barcelona: layme [Jaime] Cendrat, 1591. Digital version here.

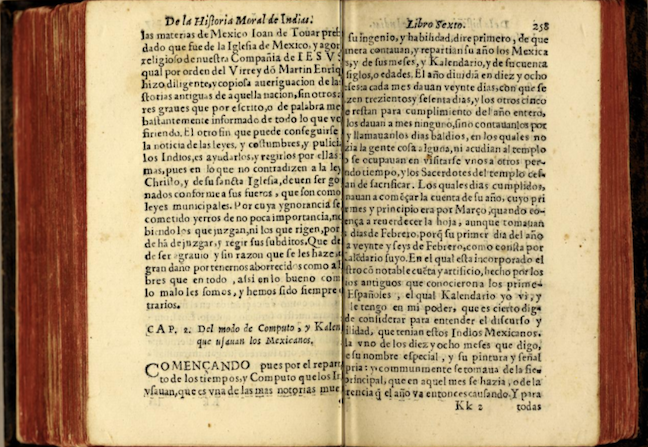

In the same way that Juan de Tovar drew upon the work of another friar to write his history, José de Acosta drew upon the work of Tovar to write his own history. Acosta’s Historia natual y moral de las Indias examines mineral, plant, and animal life, as well as the religious and political practices of indigenous peoples. Not only does Acosta mention Tovar by name as one of his sources, but he also reproduces portions of text that appear in Tovar’s manuscript in his section recounting the migration and dynastic history of the Aztecs.

1582–87, Ink on European paper, Mexico.

Digital version here.

In Book Six, Acosta provides a description of a Mexican calendar wheel that he had in his possession, which is strikingly similar to one pictured in the Tovar Codex, though it is probably not the exact calendar he was referencing. He describes the wheel as having a sun painted in the center from which four arms extend to the edge of the circle, each with its own color of green, blue, red, or yellow. Each arm was divided into thirteen sections and was associated with one of the Aztec year signs: house, rabbit, reed, or flint. He goes on to say that events that took place in each year would be painted next to the corresponding year. Though Acosta’s work is written in alphabetic script and privileges the Latin letter, he relies on both pictorial and alphabetic sources to inform his understanding of Mexican history.

Later in Book Six, Acosta questions the precision with which Mexican picture writing could preserve history, as seen in the correspondence between Tovar and Acosta at the beginning of the Tovar Codex. Yet he nonetheless praises the ways that Mexican youths learned oral discourses with exactitude and admires the ways in which indigenous parishioners wrote the general confession with pictures.

Proselytizing With Image and Text

Soon after the Spanish invasion of Mexico in the sixteenth century, missionaries attempted to convert and indoctrinate indigenous peoples in the Catholic faith. Their methods relied on adapting indigenous traditions of picture writing while also introducing new tools, such as the alphabet and oral sermons in Nahuatl for further propagating Catholicism. The forced conversion of indigenous populations was one aspect of Spain’s colonizing project in the New World, and the embrace of Catholic dogma reflects that unequal power structure. However, Nahuas were still able to maintain the use of pictured text, and they continued to reshape and innovate their cultural expressions in response. In producing syncretic expressions of faith, indigenous communities who practiced Catholicism transformed picture writing to produce new types of texts – specifically pictorial catechisms. Long considered to be a solely sixteenth century phenomenon, recent scholarship on the subject has extended their production and use to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Pictorial catechisms provided tangible material related to church doctrine, while also reclaiming and reaffirming identity by recalling an indigenous past that legitimized the documents’ creators in the contemporary moment. This section details the use of picture writing and alphabetic Nahuatl in colonial Catholic proselytizing contexts, starting with the adaptation of pictorial writing by friars, and the later adaptation by indigenous nobles. Together, these texts present a diachronic account of religious writings in colonial Mexico, establishing the complex negotiations that took place over script and pictorial form between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

Presented by Parker Zane.

Indoctrinating with Pictures

native Americans are taught their catechism.”

Perugia: Pietro Giacopo Petrucci, 1579. Digital version here.

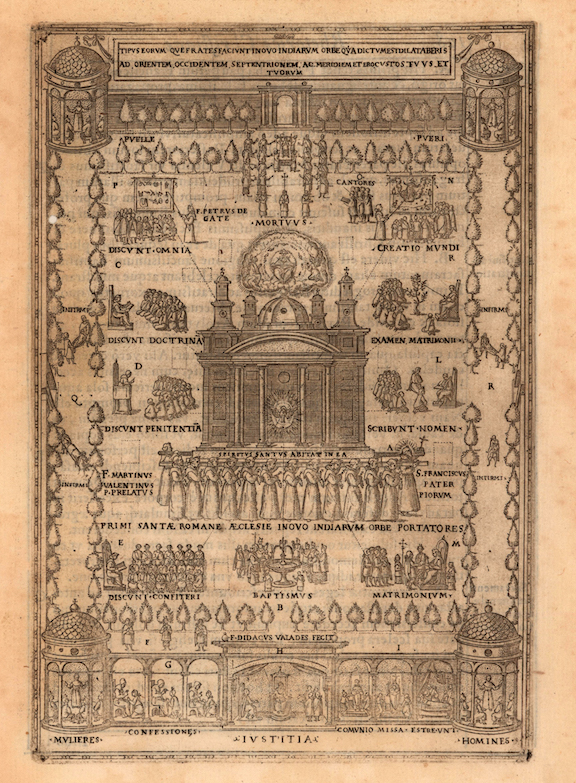

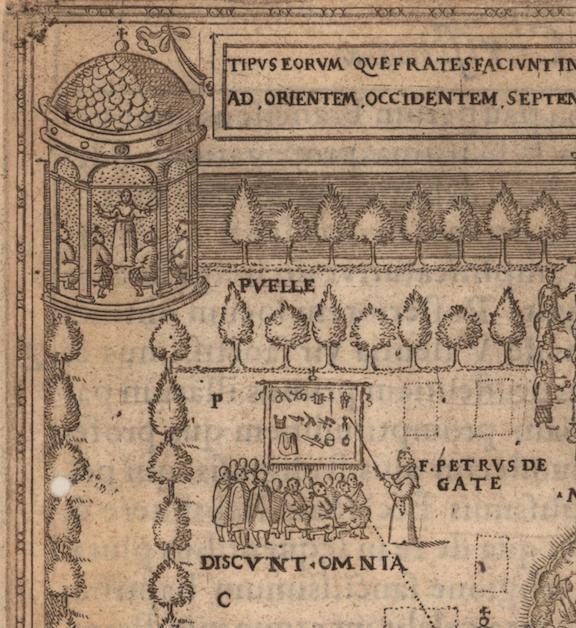

Diego de Valadés’s Rhetorica Christiana (1579) centers on the theological issues of proselytizing indigenous peoples in colonial Mexico. His engraving of a Franciscan atrium demonstrates the instructive practices of missionaries to indigenous neophytes. Friars are shown describing the creation of the world, discussing doctrine, and explaining penitence, among other depictions of sacraments and tenets of the Catholic faith. In the upper left corner of the page, a friar, Pedro de Gante, gestures towards a page covered with what appears to be pictographic writing.

Gante in “Model by which native Americans are taught

their catechism.” Perugia: Pietro Giacopo Petrucci, 1579.

Digital version here.

Pedro de Gante was one of the earliest friars to arrive in New Spain. He translated the Christian doctrine into Nahuatl and set up a school for the children of indigenous elites in Mexico City, San Jose de los Naturales, whose curriculum included fine arts and trades, as well as the liberal arts. Gante is shown before a group of native pupils. This scene has been interpreted as an early depiction of Europeans using picture writing to convey Christian doctrine to an indigenous community. While it is not clear what exact scriptural text the images in Valadés’s engraving depict, it is nonetheless an important illustration of the ways in which pictographic writing was reshaped and repurposed within a sixteenth century colonial context.

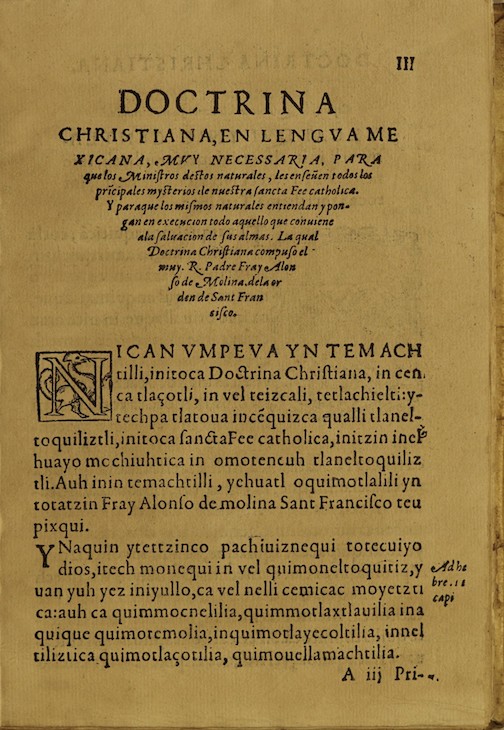

Spoken Language and the Latin Alphabet

mexicana, Mexico: En casa de Pedro Ocharte,

1578. Digital version here.

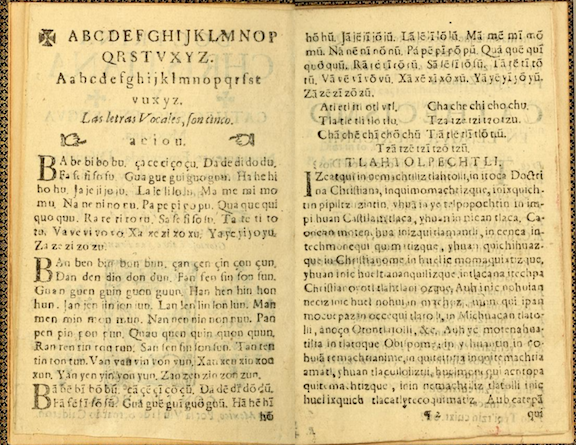

Catholic missionaries drew upon a variety of tools to indoctrinate indigenous neophytes, including the development of alphabetic Nahuatl to translate religious texts word-for-word. Alonso de Molina, a Franciscan perhaps best known for his Vocabulario en lengua castellana y Mexicana (1555/1571), a seminal Spanish-Nahuatl / Nahuatl-Spanish dictionary, also wrote an alphabetic catechism in Nahuatl. Many later editions of this catechism were printed between its original publication date in 1578 and the eighteenth century.

Because there is not a clear one-to-one correspondence between the phonetics of the Latin alphabet and the sounds of Nahuatl, complex negotiations took place in order for the Latin alphabet to functionally represent Nahuatl. Compared to pictorial writing, alphabetic writing relies on a fundamentally different mode of reading – it is purely phonetic. In this 1675 edition, the introductory pages visualize the new alphabetic script. It presents a combination of consonants and vowels – both short and long – in every consonant-vowel syllable combination that Nahuatl allows. This presentation indicates the novelty of the script to the reader and that this text was part of the beginning of a new, untested tradition.

Picturing Nahua Catholicisms

Eighteenth century, Ink on European paper, Mexico.

Digital version here.

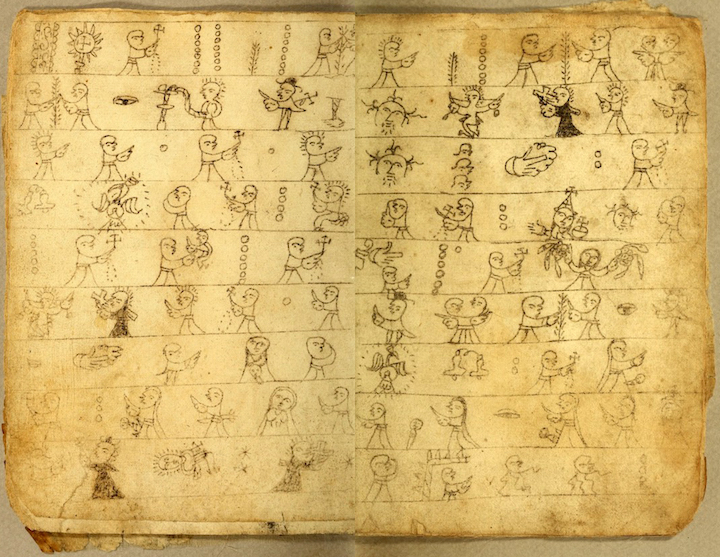

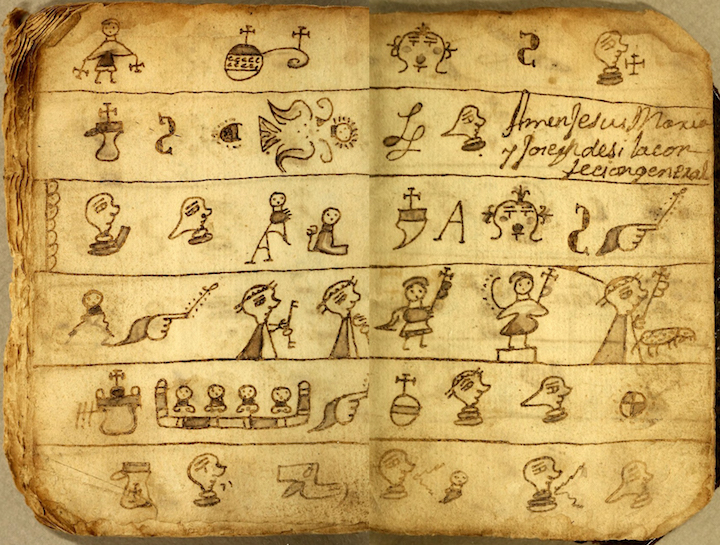

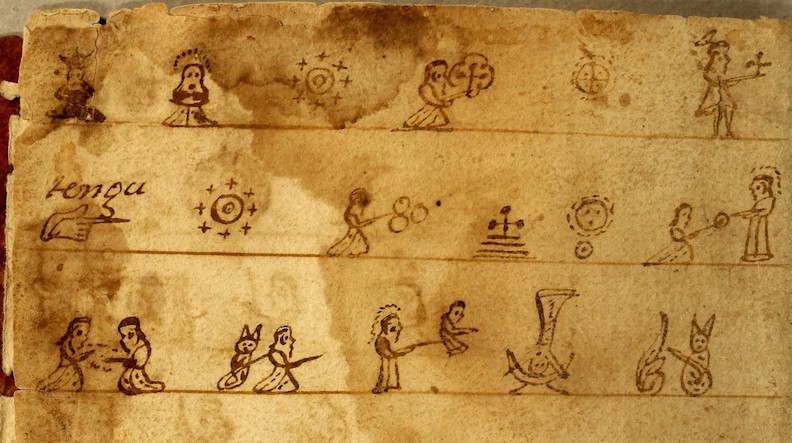

The John Carter Brown Library houses three pictorial catechisms from colonial Mexico. They summarize the Catholic doctrine using picture writing to encode Nahuatl or other indigenous languages. Importantly, this represents an innovation rather than a mere continuation of pre-Columbian picture writing into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. We see a development of a new style: pictorial signs that, while sharing some iconography with earlier manuscripts, take on new meanings and forms. The catechisms are written linearly from left to right and top to bottom across the two open pages, as opposed to the non-fixed and multidirectional forms of reading common in earlier manuscripts. As a tool for propagating and reaffirming the Catholic faith, the pictorial catechisms are extremely successful in terms of scale. The pictorial catechisms are small, portable objects intended for personal use; they can be carried around in one’s pocket, providing the reader an easily accessible opportunity to reaffirm their faith throughout the day.

Constructing a Pictorial Catechism

century, Ink on European paper, Mexico.

Digital version here.

As pictorial catechisms are generally small texts, they only contain the most essential aspects of Catholic doctrine for worshippers. This allows for a better understanding of Nahua Catholicism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as each manuscript reflects the deeply personal religious practices of their owners. The catechisms, relying on a new form of picture writing, evoke earlier indigenous practices, and subvert norms by following a linear reading order where each picture corresponds to a specific word or phrase of Catholic doctrine, allowing faith to be expressed pictorially using indigenous languages. These texts can include such material as important prayers – such as the Lord’s Prayer and Ave Maria, descriptions of the faith’s tenets, and a question and answer section.

The pictorial catechisms draw upon multiple textual traditions, occasionally excerpting portions of older catechisms. Within this manuscript, the question and answer section has been identified by ethnohistorian and anthropologist Louise Burkhart as part of the “Little Doctrine”, a specific collection of questions. These questions focus on key aspects of the Catholic faith, such as the concept of the Holy Trinity, the life of Christ, and the nature of heaven and hell, to name a few.1 This specific manuscript contains a version of the “Little Doctrine” that features nineteen questions.2 Variations on the question and answer section were propagated through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries across eleven indigenous languages in both alphabetic and pictorial texts.3

Reading a Pictorial Catechism

Ink on European paper, Mexico. Digital version here.

For a modern scholar, it can be difficult to read a pictorial catechism precisely. While it is possible to know the underlying text – such as what prayers are represented – understanding the meaning of the signs themselves can be difficult, as signs can vary across the entire corpus. However, for the scribe and owners of a catechism, reading these would likely have been much easier, as a catechism was often used as a memory aid to remember important doctrine rather than to learn it for the first time. The base text would already have been ingrained into the reader’s memory.

The catechism is read left to right across the two open pages. The first three lines of this leaf were identified by Nicolas León to contain the Lord’s Prayer, represented with pictorial writing.4 More work needs to be done with this manuscript before we can confidently recognize and interpret each sign, but some more stable signs appear throughout the corpus of pictorial catechisms, allowing us to guess a reading. The third sign of the first line is a circle of crosses inscribed with two nested circles. Compared to other similar signs in pictorial catechisms, it is possible to suggest a reading of heaven.

Sources

Preserving Property and Primordial Pasts

The Codex Coyoacán belongs to a distinct subset of indigenous manuscripts known as the Techialoyans. Although originally misidentified as sixteenth century manuscripts, the Techialoyans are now widely regarded as documents of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Due to the striking stylistic similarities in both image and text, as well as material composition across the Techialoyan corpus, scholars have suggested that they were made under the purview of a single studio or workshop for surrounding communities in Central Mexico.1

To indigenous populations, Techialoyans not only provided important pictorial and textual records of indigenous histories—often recounting the founding of local polities and delineating pre-Columbian dynastic lineages—but also acted as administrative documents to assert ownership over their native territories. Faced with the prospect of displacement and relocation, indigenous communities used the Techialoyan codices as both internal repositories of great historical and cultural importance, and as means of outward defense against Spanish attempts at land consolidation and redistribution.

Presented by Grace Wilkins.

Materials of the Past

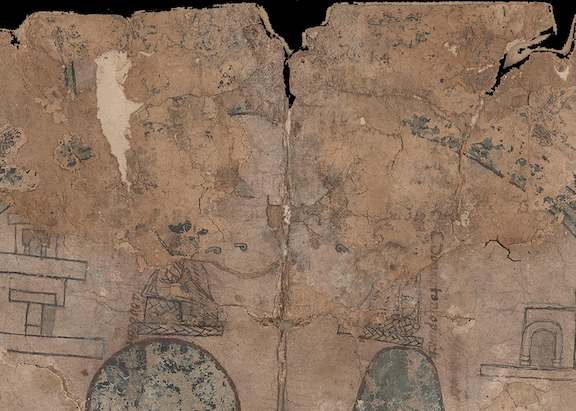

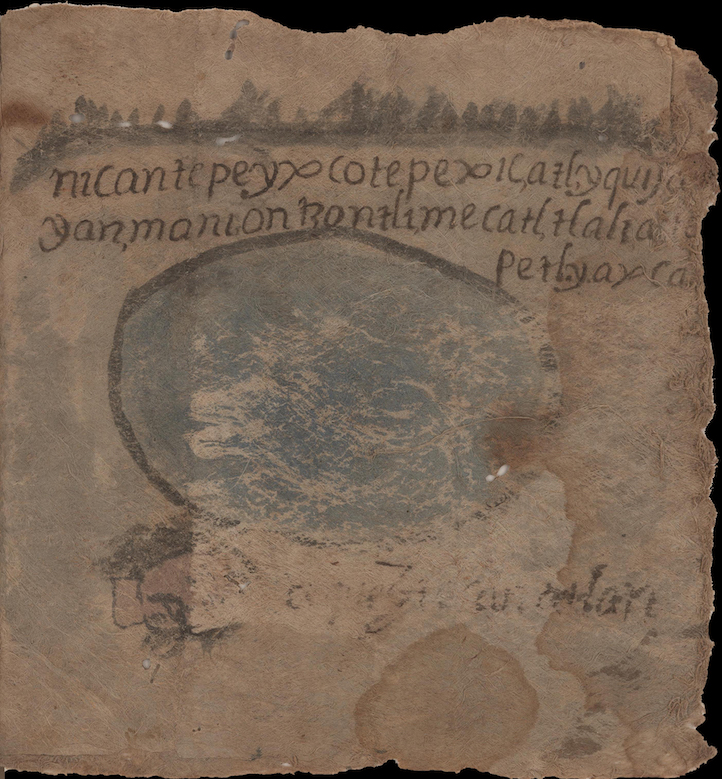

A defining characteristic of the Techialoyan codices is the use of amatl, a tree bark substrate traditionally used in the creation of indigenous pictorial manuscripts in the pre-Columbian era. Techialoyans like the Codex Coyoacán were produced by indigenous painters and scribes at a time when European paper was used commonly in Central Mexico. In fact, many Nahuatl and Spanish texts dating from the same period made use of European materials and processes of manuscript production.

It is then quite notable that the images and text of the Codex Coyoacán are presented on leaves of amatl. Each leaf of the codex is constructed from two layers of amatl, adhered together and sewn within a recto-verso book format. In the pre-Columbian period and the sixteenth century, amatl was produced in smooth, fine sheets, and was often layered with gesso, priming the surface for writing and painting in great detail. In this codex, however, the fibrous quality of the indigenous substrate is visible in the raw and frayed edges of the document and the various striations on the surface where the pigments have detached from the page. This rough material surface not only gives the pages their textured appearance but also was likely more difficult to paint and inscribe, necessitating a distinctly larger scribal handwriting.2

What, then, was the purpose of using amatl? What advantages did its use confer? Before the introduction of European paper, amatl constituted an essential means of recording information and preserving pre-Columbian pictorial histories, lineages, and territories. In the case of the Codex Coyoacán and other Techialoyans—made to solidify indigenous histories and certify claims to native lands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—returning to this traditional method of paper production lent these codices and the histories they preserved a sense of tangible historicity. The very presence of the material placed these documents within a broader lineage of earlier indigenous histories, invoking traditional processes of making and telling and resulting in a prudent and legitimizing alignment of the colonial present with a material indigenous past.

Picturing Places

amatl, Mexico. Digital version here.

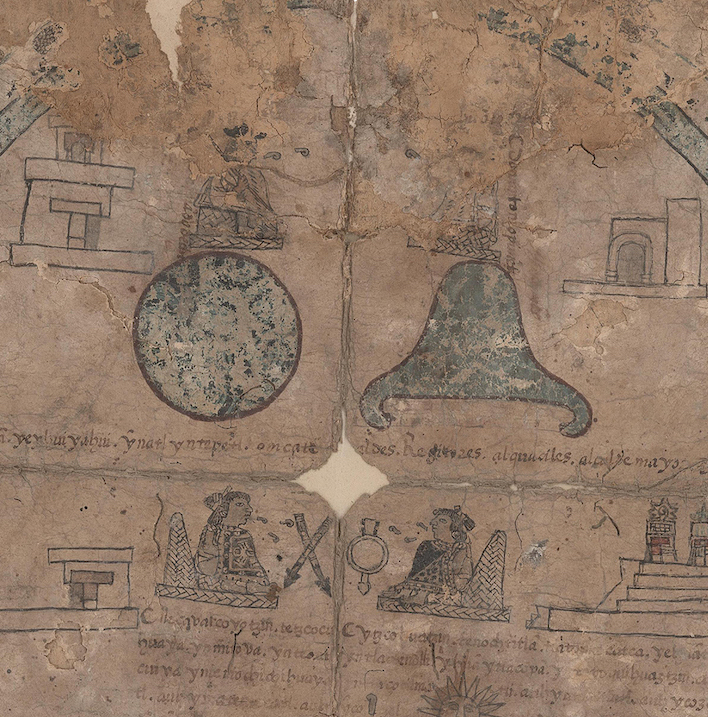

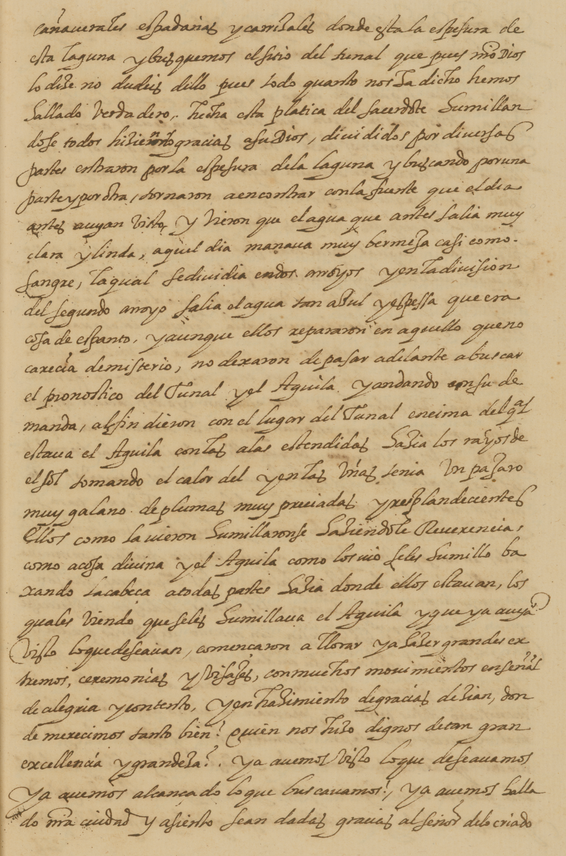

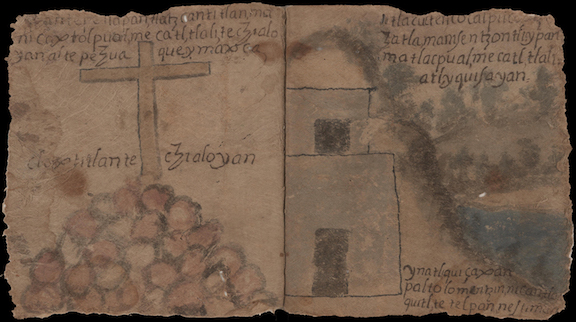

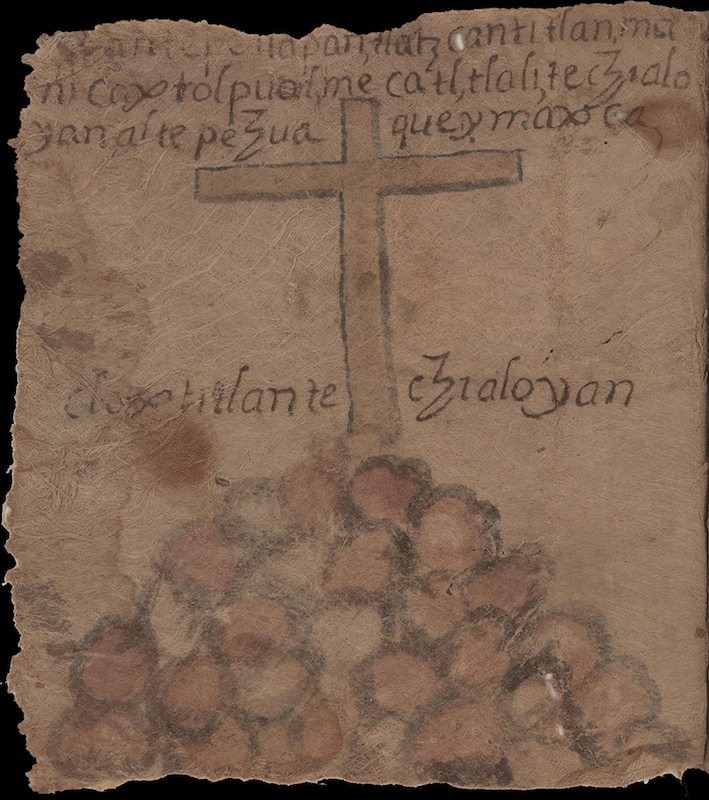

These folios of the Codex Coyoacán detail through both image and text the boundary locations pertaining to the altepeme, or indigenous pueblos, of Tetelpan and Coyoacán. On the left page, a cross stands atop a stone mound, surrounded by Nahuatl alphabetic script that names the place as Cloxtitlan and delineates the 300 mecatl—a unit of measure roughly corresponding to 120 x 120 square feet of land—as belonging to the members of the altepetl. The opposite leaf contains an image of a structure painted within the outline of a hill, accompanied by a landscape of trees and water that fills the rest of the page. These images, like the cross, are accompanied by Nahuatl text that details the amount of land at or near a spring that belongs to Tetelpan.

and ink on amatl, Mexico. Digital version here.

While these images could be read as wholly figural—merely representations of the places described in the text—they in fact call upon an enduring practice of glyphic writing established in pre-Columbian pictorial histories. The visual vocabulary of pre-Columbian codices is replete with ideograms that convey an expansive array of places, objects, and concepts. Of particular interest here is the convention of the toponym, or place-name, that encoded the name of a place with a succinct visual cue. Such toponyms frequently took the form of a hill glyph, a slightly rounded mound with a signifying image placed at the top.

It is with an understanding of this historical precedent that the images in these folios of the Codex Coyoacán should be read as both representational images and glyphic symbols—engaging in both past and present modes of encoding spatial and geographical information. The cross and the mound on the left page, for example, are not just features of the landscape that demarcate a territory, but, in fact, also act together as a symbolic cue for the name of the place itself, Cloxtitlan, which means “Beside the Cross.” In the same way that the use of amatl evoked a past pictorial tradition, these allusions to traditional visual devices perform an archaizing function, legitimating this codex within the framework of the past to serve the needs of the colonial present, and to preserve local histories for generations to come.

The Primacy of Image Over Text

Mexico. Digital version here.

The invasion of the Spaniards in the sixteenth century precipitated the widespread adoption of alphabetic text in Mexico—a marked shift from the principally oral and pictorial histories produced and performed in pre-Columbian society. The formation of a Nahuatl alphabetic script allowed for an additional type of historical record separate from the purely pictorial and oral traditions of the past. Yet by the turn of the eighteenth century, when the Techialoyans were produced, indigenous scribes still drew upon painted images to recount the past. The now preferred means of documentation and communication included a combination of both image and alphabetic text. The two, in tandem, acted as complementary vessels of information, and it was increasingly rare for images to exist independently of their associated texts.

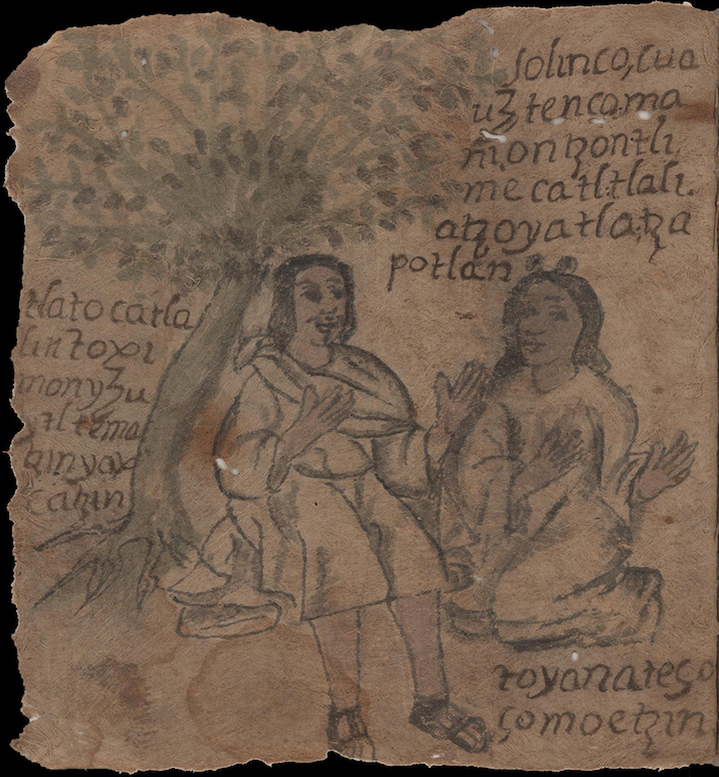

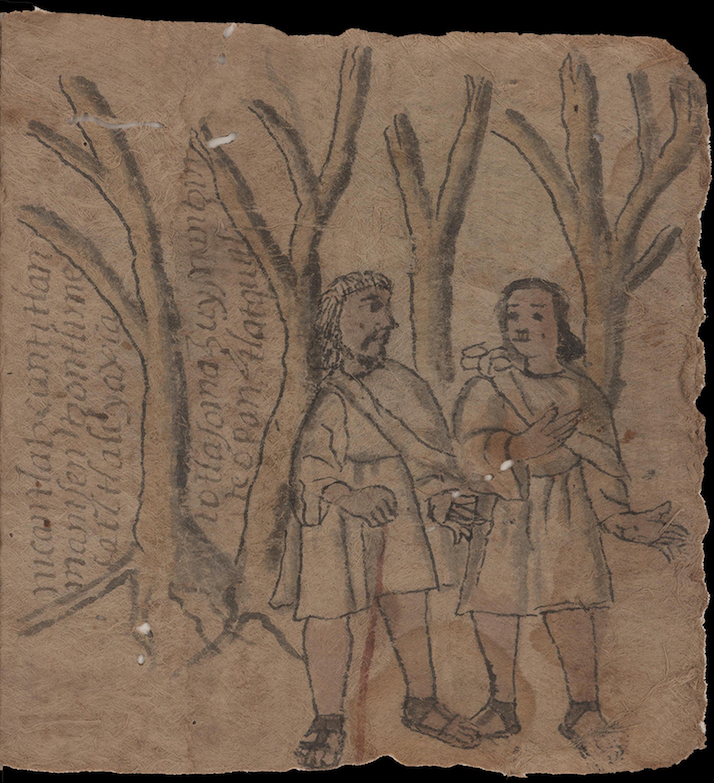

amatl, Mexico. Digital version here.

Importantly, however, there are a number of instances in the Codex Coyoacán where images take precedence over text. The relationship between text and image in this folio is particularly telling. As is especially evident in the vertical script situated between the trees on the right, the alignment and orientation of the words is determined by, and must accommodate, the space as it is delimited by the boundaries of the pictures. Such an arrangement evidences a sequence of production in which the image was executed on the amatl before the inclusion of the alphabetic text. Here, the images act as the primary point of reference with the accompanying text addressing the pictures that precede them, serving a role not unlike the explanatory oral component of the pre-Columbian pictorial histories.

Sources

Related Events

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

Credits

This exhibition was curated collectively by undergraduate students in the Spring 2020 course HIAA 1151: Painting Indigenous Histories in Colonial Mexico: Andres O’Sullivan-Comparan, Grace Wilkins, and Parker Zane. Course Instructor: Jessica Stair.