Bound Images

La Condamine

by Ernesto Capello

What is a mountain? Prior to the late eighteenth-century definition of mountains as the result of geological processes, local traditions identified sites as distinct as Mont Blanc – the highest peak in Europe – and the Mountain of Reims - an escarpment of some 280 meters in the Champagne region – as ‘mountains.’ (1) Maps reflected this ambivalence, signaling changes in elevation through pictorial representations of individual peaks with minimal attention to altitudinal differences or the specific contours of individual massifs.

A novel approach to transcend these limits can be seen in Charles Marie de La Condamine’s travelogues describing the Franco-Hispanic Geodesic Mission to Quito (1736-42). Beginning with Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi, a l’equateur (1751) and continuing with Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l’hémisphere austral (1751), La Condamine deploys a mixture of textual and imagistic evidence to establish the impossibility of describing the Andes by traditional methods, and in the process establishing the need for a new form of representation. (2) This culminates in a dramatic, multi-perspectival profile of the equatorial Andes, deploying the tools of geodesic triangulation, a profile view, and mnemonic symbols such as volcanic smoke to both reinvent mountainous cartography and evoke a reader’s memory of earlier points across his narrative.

La Condamine and his partners traveled to the Spanish colony to measure the arc of the equatorial meridian and, for good measure, scientifically prove Newton’s theory of gravity. Their primary activities consisted of determining the length of a degree of latitude at the equator by means of a process called geodesic triangulation, which necessitates making precise visual measurements along a chain of imaginary triangles that delineate the contours of a portion of the curved planetary surface.

In his two travelogues, La Condamines presented an interplay of text and image (or paratext) to describe the Andes. As he notes, the double chains of the equatorial Andes “proved favorable for the measurement of the meridian,” yet excessive cloud and snow cover often obscured the very peaks he hoped to measure. This situation led him to identify two central perspectives - a geological or longitudinal view considered a boon to the expeditions and, alternately, a series of invisible, impassible, and individual points where fog, cold, and terrain interfered with his measurements. We might also consider these as an overhead projection – often referred to as a God’s eye view – and a ground-based projection, or what we might term a Man’s eye view.

La Condamine develops a dramatic distinction between these two perspectives in his travelogues. The first, Journal du voyage, could be viewed as focusing on the points. The text highlights the difficult terrain the scientists encountered while the images emphasize individual moments – La Condamine carving his name on a rock on the equatorial coast, the measuring of the geodesic baseline in the Yaruqui plains, and, especially, the building of ceremonial pyramids at the ends of this baseline. The second, Mesure de trois premiers degrés du méridien, on the other hand, focuses on the scientific results and features images of the longitudinal view. This begins with the frontispiece (FIGURE 1), which incorporates a globe with a compass splayed across the three degrees of equatorial latitude measured by the French scientists. The two main parts of the book are introduced with images of geodesic measurement, including the measuring of a horizon angle with a quadrant and the sighting of the north star with a telescope, both necessary steps in the process.

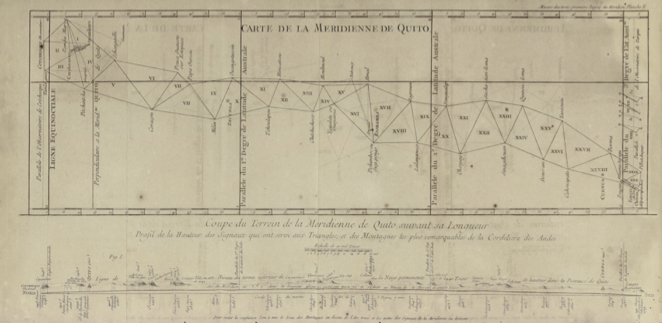

The highlight, however, is the dramatic reconsideration of the mountain range as a geological formation instead of a collection of individual peaks or mountains. La Condamine built upon multiple traditions in the revolutionary image (FIGURE 2) he published in this volume. Influences included the medieval tradition of coastal relief profiles included in portolan charts, a rudimentary Andean profile presented by his colleague Pierre Bouguer a year earlier, and La Condamine’s own inclusion of three-dimensional images of major volcanoes like Cotopaxi in his colleague Pedro Vicente Maldonado’s map of the Spanish province of Quito, published the previous year.

La Condamine’s final profile of the equatorial Andes, however, far eclipsed these examples. It includes not only a relief profile but also a dramatic inclusion of three-dimensional peaks including Cayambe and Chimborazo, and perhaps most dramatically, Cotopaxi, with its distinctive conical peak and a plume of smoke reflecting an eruption the group had witnessed, which had been described earlier in the narrative.

The genius in La Condamine’s map, however, lies in his juxtaposition of this profile with an overhead view of the geodesic triangles arranged at the same scale. As such, the reader of the map can view both a profile as well as an orthogonal projection simultaneously and match the points of the triangles with the peaks of the longitudinal profile. Moreover, the heights of the major peaks as well as of the geodesic signals are also marked, information that highlights both the grandeur (quite literally) of the Andes but also the perspicacity of La Condamine and his colleagues in braving such high places.

In essence, in this map La Condamine found a way to bring together the two points of view that dominate his two narratives – the God’s eye and the Man’s eye views. Both the Andes as a boon for measurement and as an inhospitable terrain for the scientist are readily apparent in a simple and elegant, multi-perspectival arrangement. However, only readers of the first travelogue, Journal du voyage, would be able to fully apprehend the multiple layers of meaning illustrated in the image. That is to say, only these readers would be able to appreciate the significance of individual peaks like Chimborazo with its intense altitude or Cotopaxi with its volcanic eruption, each highlighted pictorially in the profile. Moreover, only these readers would be able to consider the individual points of the geodesic triangles which had been described as impassable or unmeasurable in the prior volume. And as such, only they would be able to understand how the image demonstrated the “taming” of the Andes while also acknowledging their specific contours and their unknowability, at least as measurable by the instruments of the day.

__________

(1) Bernard Debarbieux and Gilles Rudaz, The Mountain: A Political History from the Enlightenment to the Present, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Chicago: Univeristy of Chicago Press, 2015), 13-16.

(2) Charles Marie de la Condamine, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi, a l’equateur, servant d’introduction historique a la mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien (Paris : Imprimerie Royale, 1751), and Charles Marie de La Condamine, Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l’hémisphere austral, tiree des observations de Mrs de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, Envoyés par le Roi sous l’Équateur (Paris: Imprimerie Royal, 1751.)