Bound Images

Vue de l’Habitation du Sr. de Préfontaine Située à Cayenne

by Bertie Mandelblatt

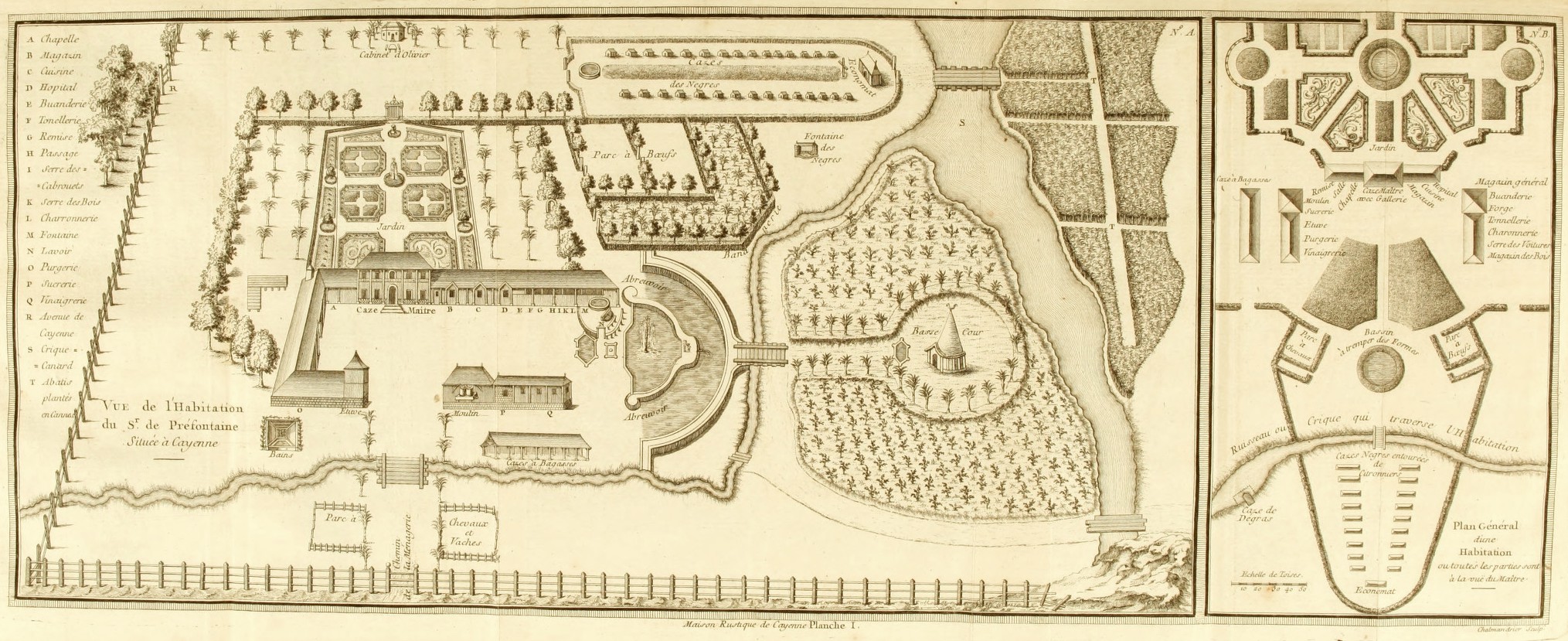

A set of two idealized estate plans are contained in the first of the seven plates that conclude the Chevalier de Préfontaine’s 1763 guide to creating a commercial plantation in the French colony of Guyana. With graphic effectiveness, the plan both encapsulates and propels forward the complicated personal history in the region of its author, and the confused imperial aspirations of his powerful supporters at the court of Louis XV, notably the Duc de Choiseul.

The power of the estate plan is, at least partly, due to the fact that it is both descriptive and prescriptive: two thirds of the plate is devoted to a birds’ eye perspective plan that claims to depict Préfontaine’s own plantation, and one third to a generalized plan of a potential plantation. At the time of the book’s publication, Préfontaine had been in French Guyana almost 30 years, first arriving as a naval lieutenant in the late 1730s, before inheriting, through a 1752 marriage, a series of plantations in Macouria, in the outskirts of Cayenne, the capital of Guyana. After France lost its vast North American possessions after its defeat in the Seven Years War, Choiseul (then Naval and War Minister) – and a close circle of advisers – devised the ambitious project to develop Kourou, a coastal site close to Cayenne, as a colonial settlement amongst whose functions numbered replacing Canada as a source of provisions for Caribbean colonies. Préfontaine played an essential role in these designs as the veteran planter whose local knowledge would serve the new settlement. And while the title of his guide, published at Choiseul’s behest, was directly inspired by such works of early modern agronomy as Charles Estienne’s 1554 Prædium Rusticum [Maison Rustique] and Louis Liger’s 1700 La Nouvelle maison rustique, its immediate function was to inform and assist incoming colonists.

The graphic material appended to the volume’s text places the work squarely within the genre of Enlightenment science. It is grouped together at the end of the text, preceded by an explicative note, not scattered throughout the work such as in Pierre Barrère’s earlier work of ethnography of the 1740s. This material includes detailed diagrams related to the production of commercial products (cotton, sugar, roucou, indigo), of the architectural details of plantation structures, and of the procedures tied to subsistence and transport. The two exceptions to the diagrammatic nature of the visual material are, first, the plate of the two estate plans under discussion here, and, second, a plate illustrating of cassava production, neither belonging to the genre of scientific illustration but rather purporting to represent the practice of everyday life in tropical plantation settings, albeit in differing graphic modes.

Together, the two plans on the first plate offer images of harmony, balance, and complete control, providing panoptic overviews of the structures and sites whose procedures are broken down and explained in the succeeding plates. Their role was to provide reassuring graphic evidence that, not only was successful plantation management possible, but, in addition, standards of European civilized life could be maintained in a tropical setting. They subverted the evolving cartographic genre of estate plan which was developed to enable landowners to visualize their property in order better to exploit it, created by an emerging technical class of surveyors or cartographers on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. While estate plans were most often manuscript, with a limited circulation, this plan was printed. Its public was not the largely private audience of the classic estate plan: the landowner, his or her employees, and perhaps those serving in courts of law. Rather Préfontaine’s maps, and the book in which it was issued, became commercial objects that served the purpose of propaganda for the ultimately disastrous Kourou project.

The first of the two estates featured on the plate (N°A) purports to represent Préfontaine’s own plantation at Cayenne. All human elements and man-made structures are visible and ordered, contained within a perimeter created on two sides by a fence and on two sides by a creek, on the other side of which the agricultural plantations themselves begin. A legend explicates in extensive detail the function of the elements of the plan: first, an array of industrial plantation outbuildings linked to sugar production (the sugar mill, the sugar works where syrups would be cooked down, the warehouse containing crushed cane, the distillery and the ‘purgerie’ where sugar moulds were left to dry, letting impurities and syrups drain away) and corollary procedures (the production of barrels and carts); and, second, the structures required to support a sizable human population (kitchens, hospital, laundry, fountains and a chapel.)

A pivotal sign of the perfected control of the plantation owner is the effort that has been made to account for the presence and maintenance of an enslaved work force, which nonetheless provides elements that disrupt the internal symmetry and ordered nature of the plan. The rows of houses for enslaved workers are literally off-centre, placed within their own hedged perimeter away from the central compound, at the head of which is found a commissary. The representation of plantation subsistence, always a complex and volatile aspect of plantation management, also figures. At the top of the plan there is an L-shaped plot that meets the hedged perimeter of the slave compound, between the cattle pen and the fountain reserved for the enslaved population; ‘bananerie’ is awkwardly engraved on the plan’s copper plate, the lettering squeezed between the depiction of the plot itself and of a neighbouring creek. The plot is bordered by deciduous trees and the plants within resemble banana or plantain. Secondly, a larger and unnamed plot surrounds the barnyard where poultry would run ("la basse cour"), containing plants that are visually differentiated from those in the bananerie: these are possibly manioc, the predominant tropical staple of the region.

The second of the plans on the plate (N°B) is an anonymized vision of a model plantation based on Préfontaine’s counsel. The plan is characterized by an overall symmetry of layout, as well as by internally symmetrical elements (formal gardens, rows of houses of the enslaved). It includes many fewer details than the first, although it does feature (as does N°A) a set of formal, ordered gardens, whose elegance underlines the potential for creating a sophisticated, controlled and essentially European-identified plantation complex.

The authority of the two plans derives from the association of the plans with Préfontaine’s long personal experience in Guyana, as the predominance of Préfontaine’s own estate plan in the engraving makes clear. The disjuncture between the authority conferred by experience and the scale of the Kourou disaster that unfolded within a year of the book’s publication (9000 of the 10-12,000 colonists who arrived perished, and most of the survivors fled the colony) is, however, striking. To be fair, Préfontaine’s own conception of a Kourou settlement had differed in significant ways from the project ultimately put into place by Choiseul. Nevertheless, the imperial illusions of power and control cartographically embodied by the two plans proved entirely unrealizable, despite any grounding in Préfontaine’s familiarity with operating plantations in Guyana, elucidated in his 250-page plantation guide.

__________

“Vue de l’Habitation du Sr. de Préfontaine Située à Cayenne.” In Chevalier de Préfontaine, Maison rustique, a l'usage des habitans de la partie de la France équinoxiale, connue sous le nom de Cayenne. Paris: [1763]