Bound Images

Information Networks in Johann Jakob Scheuchzer’s Physica Sacra (1731-1735)

by Stephanie Stillo

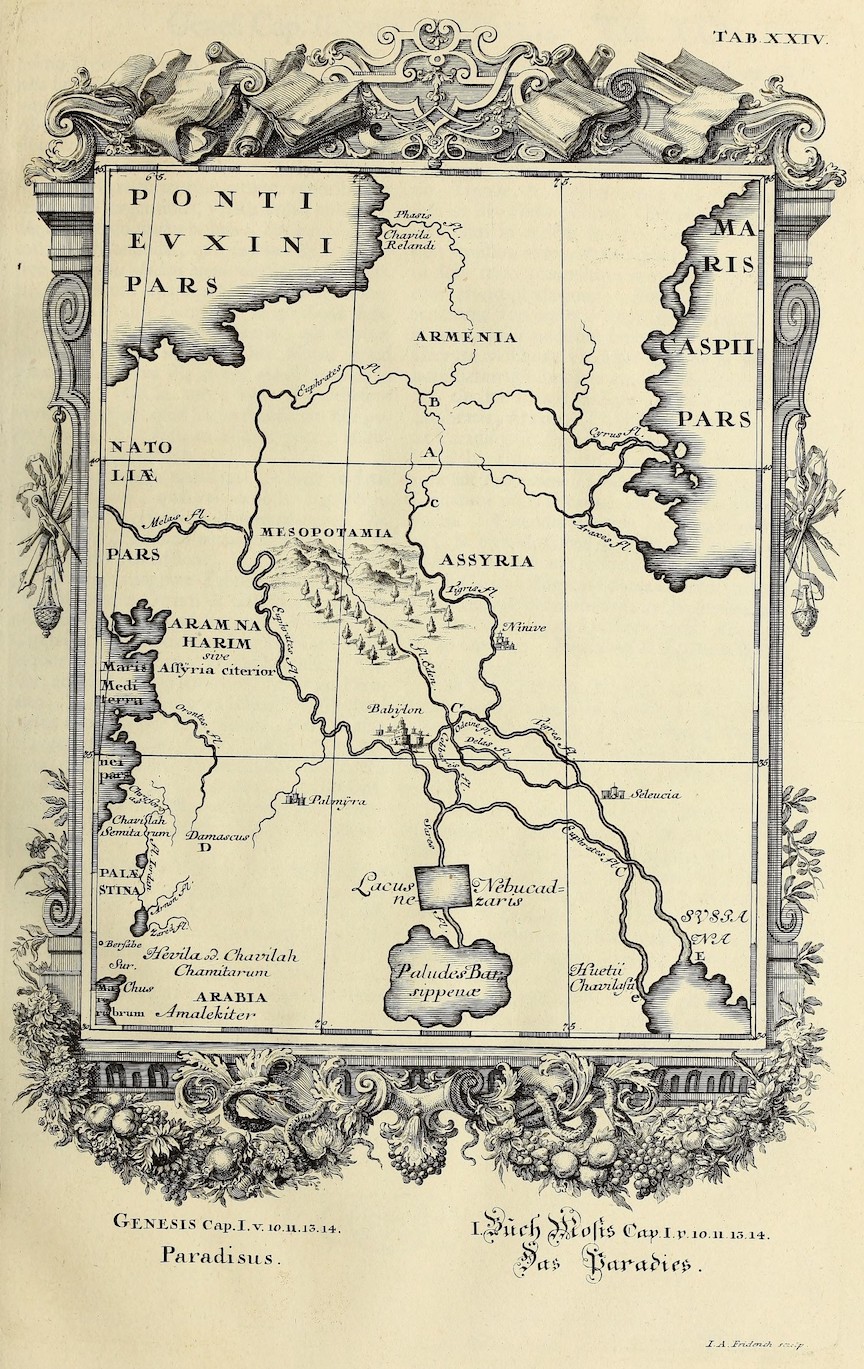

Have you ever wondered how Moses parted the Red Sea? Or how God created the firmament? How about the location of Eden? Or the measurements of Noah’s great ark? Answering these questions, along with many others, was the goal of Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer in the Physica Sacra (1731-1735). Often called the Kupfer-Bibel (Copper Bible) due its 761 impressively detailed engravings peppered throughout the four folio volumes, Scheuchzer brought together text and image to synthesize, analyze, and dissect the natural, physical, and cosmological history of the Bible.

The Physica Sacra functioned as part library and part printed cabinet of curiosity. Through textual synthesis of hundreds of scientific, historical, and technological studies applied to specific bible verses, Scheuchzer harmonized Bible stories with contemporary debates about zoology, botany, geography, mathematics, astronomy, and biology. Scheuchzer’s analysis of Bible verses included dramatic engravings of landscapes, fossils, exploded object views, and detailed architectural schematics, all with the express purpose of deciphering the mysteries and miracles of the Old and New Testaments. Descriptive borders with dissected flora and fauna, skeletons, tools, coins, and cameos surround the principle explanatory images. Many of the elaborate border images encroach on the principle frame, creating an intimate and immediate connection between the explanatory text, narrative scene, object, and bible verse; a space devoid of division between the natural, artificial, and divine.

It is more appropriate to call Scheuchzer the architect, rather than author, of the Physica Sacra. He drew many of the artificialia and naturalia from examples in his own extensive cabinet. However, many illustrations in the Physcia Sacra were far from original. Scheuchzer borrowed heavily from popular illustrated books. For example, to visualize his textual analysis of Leviticus 11: 9-12, in which God commanded the Children of Israel to eat whatsoever hath fins and scales in the waters, in the seas, and in the rivers, Scheuchzer copied images from Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665), specifically his microscopic images of the scales on “soal” fish. (Tab. ccxxxix, vol. II). Figure 1. Scheuchzer relied most heavily on the visual content and presentation style of Dutch botanist and anatomist Frederick Ruysch and his popular early eighteenth-century Thesaurus Anatomicus (see Homo ex Humo Tab xxiii vol. I and the presentation of goat and cattle stomachs Tab. ccxxx-xii, vol. II) .

It would be tempting to consider the role of Scheuchzer’s maps in the Kupfer-Bibel as limited to that of independent, dispassionate images; visualizations of geographic realities best served through a singular cartographic image. Instead, the maps in the Physica Sacra are as much an act of interpretation and analytical synthesis as Scheuchzer’s descriptions of fossils or zoological specimens. They serve the same function as the work’s other interpretive images, helping the reader navigate to different parts of Scheuchzer’s larger network of information. For example, Scheuchzer’s map envisionsthe relative geographic locations of the four rivers that flowed from Eden (Pison, Gihon, Hiddekel, and Euphrates) per Genesis II: 10-14 (Tab xxiv vol. I, entitled Paradisus).

The map (figure 2) is a visual synthesis of numerous theories presented by contemporary authors including German humanist Johannes Sturm, Pierre Daniel Huet, founder of the Academie du Physique in Caen, and French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort. The map is also in direct communication with a visualization of Genesis II: 12 (Tab xxv vol I).

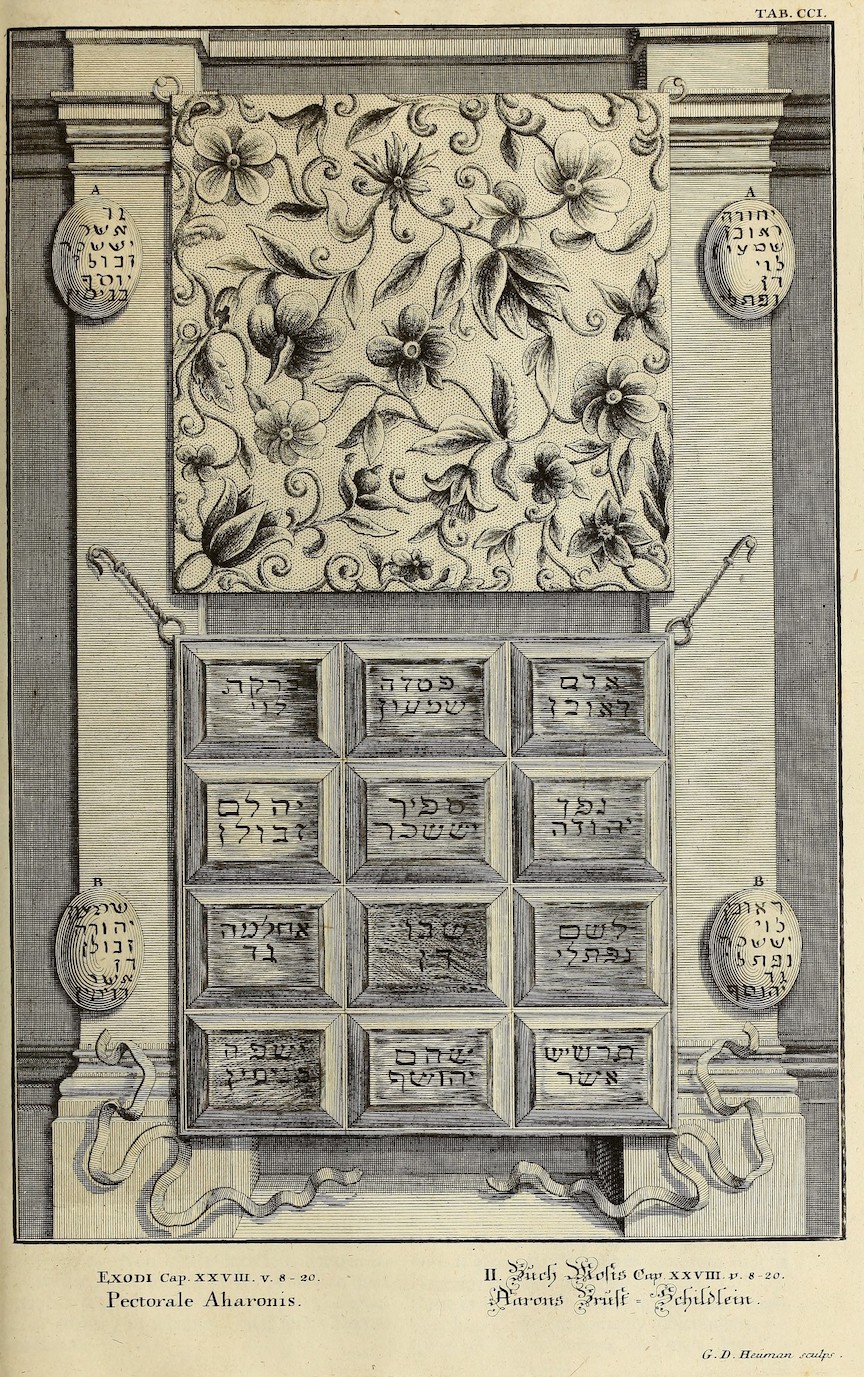

Figure 3, which debates the natural environment of the Havilah region in the Paradisus map. Here Scheuchzer presents a debate about the meaning of the Hebrew word bedolach, visualized as either rock crystals, pearls, or an aromatic gum resin used for perfume and incense. The final textual section on lapis (jewels) helps the viewer to further navigate the larger information network of the Physica Sacra with directions to an illustration of Exodus 28: 20 and 39: 6 (featured in Table cci-ccii, vol I).

Figure 4, which depicts the bejeweled breastplate made for Moses’ brother Aaron, the first High Priest of the Israelites. If isolated, the Genesis map is, at best, unclear. However, when combined, as Scheuchzer intended, with a textual description that offers interpretation and suggestions for related images, the map becomes a part of a much larger argument about the physical and geographical interconnectedness of the Old Testament.

In sum, the maps in the Physica Sacra played the same role as other images in the Kupfer-Bibel. They were visualizations of textual interpretation, and only when read with other text and images (both within and outside the four volume anthology) did they convey their full meaning and significance. To view them as sovereign images would be to misinterpret their role in the project and to miss important navigational markers in Scheuchzer’s larger information network.

__________

Further Reading:

Hans Fischer. Johann Jakob Scheuchzer <2. August 1672-23. Juni 1733>, Naturforscher und Arzt. Vierteljahrsschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich. Zürich: Komm. Leemann, 1973.

M. J. S. Rudwick. Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Sheehan, Jonathan. "From Philology to Fossils: The Biblical Encyclopedia in Early Modern Europe." Journal of the History of Ideas 64, no. 1 (2003): 41-60.

Bernd Roling. Physica sacra : Wunder, Naturwissenschaft und historischer Schriftsinn zwischen Mittelalter und Früher Neuzeit / von Bernd Roling. Brill: Leiden; Boston, 2013

Urs B. Leu. "Swiss Mountains and English Scholars: Johann Jakob Scheuchzer's Relations to the Royal Society." Huntington Library Quarterly 78, no. 2 (2015): 329-48.