Digitizing Mary Brown Vanderlight

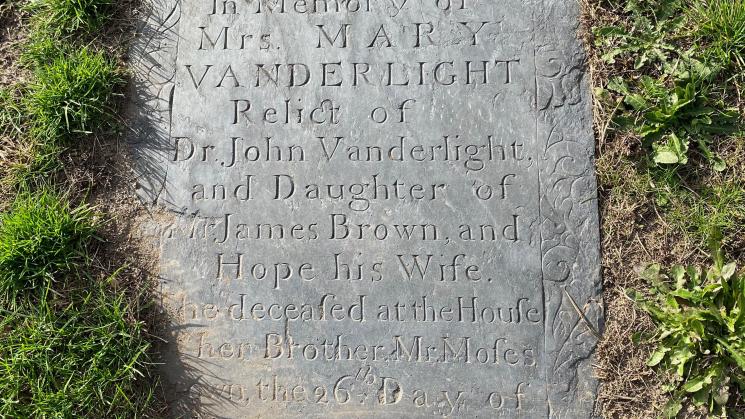

Earlier this month I was delighted to share in a JCB post a bit about the four manuscript volumes we hold related to or written by Mary Brown Vanderlight, and also information about the fuller piece on her life–or what we know about– that I wrote for Commonplace: the Journal of Early American Life. That essay, “The Brown Brothers Had a Sister,” has initiated some exciting conversations inside and beyond the library and, as predicted, has already turned up some additional, though still fragmentary, references. Alas, no stash of her letters or a diary! Still, every snippet matters as we accumulate information about people, even such a privileged person as Mary Brown Vanderlight, marginalized in archival collections.

We have now digitized and made available on our digital platform, Americana, the JCB’s contemporary volumes that tell us about the life of Mary Brown Vanderlight. These include 3 account books kept mostly by Mary of her husband David’s medical and apothecary practice and then her own finances, and the inventory of his estate. They cover roughly 1751 to the early 1760s; the inventory was taken in February 1755, just shortly after David Vanderlight’s death. You can find the account books here, here, and here, and the inventory here. Americana allows access to the digitized material alongside a suite of useful tools as well as full catalog information.

So much can be gleaned from the entries in the account books, and from linking them. I have an ambition to create a dataset from the entries in Mary Vanderlight’s daybook, but we shall see how long that takes! And in the meantime, I hope more researchers will begin to explore them and will share their insights. While I’ve used them to date to ask questions about the presence and absence of women in these records and in our histories, there are also histories of daily commerce, urban life, early New England, race, slavery, and the lives of a wide range of people including Black folks in Rhode Island, that can be further illuminated from these materials.

We are committed to continuing to expand access to the JCB’s collections, including through digitization. But there will always be reasonable questions about what can and should be digitized. These materials, for example, contain medical information– or at least, information about what the Vanderlights provided to a variety of people to address medical concerns. Health information privacy is a matter of policy now; in the United States identifiable health information is protected for 50 years after someone’s death so sharing our eighteenth-century records would not violate the law. Still, it is useful to reflect regularly on the ethical implications of the materials we are holding and sharing.

We hope you’ll let us know what you make of this material and stay tuned as we work to make other materials, including the remarkable collection of Brown Family Business Records, more accessible.