Living and Dying at Sea

How to explore the embodied experience of living at sea (and learning to sail), when there were such glaring structural differences in the everyday lives of the people who crossed the Atlantic Ocean?

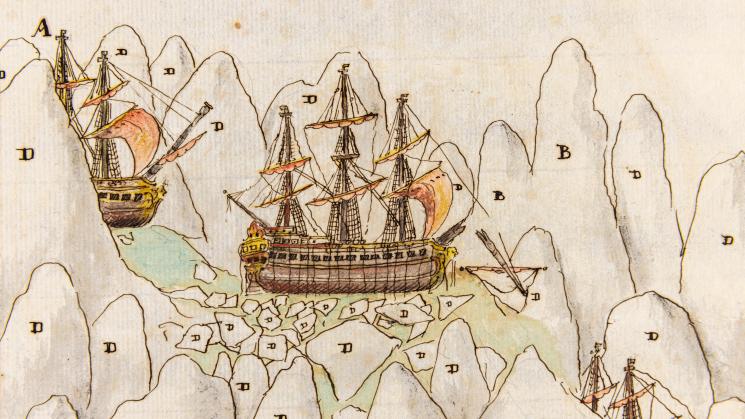

I selected the collection items for the October 2024 JCB exhibition, “Learning to Sail, Living at Sea: Vernaculars of Maritime Knowledge,” and undertook the exhibition writing with three intersecting intellectual concerns in mind, although the direct trigger for developing the exhibition was largely institutional. The JCB had acquired a three French 17th-century manuscript navigational manuals in recent years, two of which feature in the exhibition. These exceptional works are directly within the scope of the JCB’s collecting mission, so we were delighted to bring them into our collections and make them available for research. Indeed, the Library’s history of engagement with the broad field of maritime history through its collections, exhibitions and other programs, and publications reaches back to the first decades of its existence in the mid-nineteenth century.

However, as I studied these manuscripts, I saw aspects of them that revealed the deeply individual yet collectively structured experience of living at sea that seemed at odds with, although with distinct connections to, the familiar heroic narrative of the growth of the western European dominance of Atlantic Ocean navigation. That is, the embodied experience of living at sea discernable in these works was not separate from the abstraction that they present, but rather the broader story of Atlantic seafaring out of which emerged the navigational, hydrographic and nautical science and practice of the 17th and 18th centuries cannot be reduced to the print and manuscript forms it took in its own time, nor to the ways it was reproduced in 19th-, 20th- and 21st-century narratives of maritime history. Seafaring was first and foremost a question of survival in an aqueous world filled with dangers from without and within. The production of maritime knowledge through practices of observation, measurement, calculation, and inscription depended on this survival above all.

But how to explore the embodied experience of living at sea (and learning to sail), when there were such glaring structural differences in the everyday lives of the people who crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the period of the European transatlantic trade in African captives? The trade itself was productive in death and racialized violence in the Middle Passage in ways that have been recently been investigated by scholars such as Sowande' M. Mustakeem and Stephanie Smallwood. Drawing on research by these scholars and by those contributing to the thriving field of maritime history from below, I sought to highlight the complexities of the central questions of embodiment and survival, and possible answers to them, across the range of collection items I selected for the exhibition. These items combine manuscript and printed sources across four languages, and include a wide range of texts (manuals, memoirs, histories, polemics, log books) as well as graphic material (maps, charts, atlases, watercolors), including archival documents such as letters, portage bills and even poetry.

The exhibition is presented in six sections, all animated by three intersecting intellectual poles. The first of these poles concerns embodiment and the everyday. The exhibition explores the realities of human life at sea, presenting as a case study, a selection of materials related to food consumption and stowage on board ships. The ship was, before anything else, a physical space where men and women lived for weeks on end (and sometimes died), and one of the main determinants of survival was the ability of ships to provision themselves effectively, a set of demands that bedeviled European navies and merchant vessels for centuries. The exhibition features an intimate and harrowing glimpse of the twin process of birth and death themselves, allowing us to consider how these acts were represented in text and in images and to what end. Finally, first-hand observation of the dangers and beauty of world at sea was certainly the most common embodied maritime experience – observation that was manifested in both textual and graphic sources – and it is an element of several of the exhibition cases

The second intellectual pole is that of the seaborne subject’s relationship to the process of documentation: who had access to commercial or institutional printers and publishers, and, once printed, which maritime narratives were then able to circulate, becoming a matter of record? Other than official or elite access to the machinery of publishing, were there other factors that facilitated the move of certain texts and images from manuscript to print, such as the active support of concerned political or religious groups, like Christian abolitionists in 18th-century Britain for example? How and why did certain mariners succeed at fashioning their identity through the publication of memoirs or accounts of voyages? And what does the manuscript record – both textual and graphic – reveal to us, as 21st century audiences, that is possibly absent from the printed record? The relationship between print and manuscript, between sanctioned and unsanctioned maritime knowledge are explored throughout the exhibition, which foregrounds the practices of journal keeping and vernacular expression.

The last of the intellectual poles relates to the question of shipboard social hierarchies, and how crucial social distinctions were forged both through the training of mariners and the practices and routines of life at sea. Social hierarchies were an integral component of shipboard life on both naval and merchant vessels, and the exhibition features a number of instructional navigational manuals aimed at and produced by strikingly different social groups, manuals that both reflected these social hierarchies and taught men their place within them. The greatest social divisions on ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean was, however, that between the free, the captive, and the enslaved, an ensemble of identities each of which was actively created at sea through daily rituals and practices. The violence of these shipboard practices imposed on African-descended captives who were kidnapped in the context of the transatlantic trafficking of humans is ubiquitous in the primary sources that testify to seafaring life in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the representations of that violence in this exhibition are startling and profoundly unsettling, and we therefore decided to print a content warning on the exhibition’s publicity in order to alert audiences to potential distress.

As a rare book library with a mission to actively collect textual and graphic materials related to the early Americas and to make these materials available to research, our responsibilities are two-fold: the first is to not hide the violence inherent in these works away nor to pretend that it does not exist, but instead to openly recognize its omnipresence; the second responsibility is to not treat this material casually or lightly, but rather to carefully, selectively and intentionally present it in its context and to open up avenues for conversation. This exhibition seeks to tread this path.

Photo credit: Rythum Vinoben.