Resisting slavery on the Belvidere Estate in Jamaica

The inner lives, the personalities, histories, and culture of African and African-descended people were obscured and deemed illegitimate and irrelevant in the surviving records. And yet there is an inherent tension inscribed in these dusty old White-created documents, for they all refer to her resistance.

Her parents were still young and she was not yet born when the plan for the Belvidere Estate was drawn up in 1772. Her parents most likely lived in West Central Africa, in a matrilineal and largely rural society within the Kingdom of Kongo. It was a large society, both geographically and numerically. Although there was some mining of copper, iron, and gold, along with associated crafts, most people worked in a remarkably diversified agriculture, which included corn, manioc, peanuts, sweet potatoes, pineapples, bananas, peppers, sugar cane, and palm oil. Women did much of the agricultural labor, and perhaps the woman who concerns us became familiar with this work during her early years. But then she—perhaps with other members of her family and community—was taken up and sold to traders, and transported to Jamaica. In the nearly two decades between this woman’s birth in about 1790 and the end of the legal slave trade in 1808, almost 200 ships brought about 60,000 people from West Central Africa to Jamaica, almost one-quarter of all Africans brought to the island during these years. Kitty Thomson was one of them.

Of course that was not the name her parents gave her. It is the name that identifies her in documents in the National Archives in Kew, the Essex Record Office in Chelmsford, and in issues of two Jamaican newspapers, the Cornwall Chronicle and the Royal Gazette. We do not know how old she was when she was enslaved and endured the Middle Passage. Nor do we know who purchased her, and where she worked after her arrival. For a while she was enslaved on a small coffee plantation called Newfield in the parish of St Thomas in the East in southeastern Jamaica, which lay on higher ground between the coast and the high peaks of the Blue Mountains. But this was probably not her first place of enslavement.

Kitty Thomson was no longer at Newfield when she appeared in a list of enslaved people who were confined in the Kingston workhouse, which was published in the Cornwall Chronicle in October 1816. The entry is short, naming and describing her as “KITTY, a Mungola, to Belvidere Estate.” The record also reveals that she was marked with several branded initials on her left shoulder. Jamaican newspapers were required by law to publish lists of all enslaved people who had escaped and been incarcerated in workhouses and jails, as well as all others who had been sent to these institutions for punishment for various offences, perhaps to be whipped or made to work in harsh conditions away from their community as punishment. The words “to Belvidere Estate” indicate that Kitty Thomson fell into this latter category. Thus, the first record we have of her is one that indicates she resisted to the extent that she faced serious punishment. Being sent to the workhouse usually occurred after several offences and punishments on the plantation.

A year later, in 1817, Kitty Thomson’s name appeared in an inventory of the enslaved people at Belvidere, which today is held by the Essex Records Office, in Chelmsford, England. Her’s was a simple entry, recording her name, that she was 28 years old, and that she was African-born. It is clear that she was part of a large community: the inventory listed a total of 355 enslaved people, 182 of them male, 173 female, all of them living and working at Belvidere. 80 of those aged 23 or older were, like Kitty Thomson, African-born. But when those who were younger are included, Africans constituted less than one-quarter (22.5%) of Belvidere’s enslaved population. She was the youngest African-born female, and we can wonder about how this must have felt. Many of the estate’s enslaved people were listed with the names of partners, mothers, or children, but no name appeared alongside Kitty Thomson’s in any of the surviving lists. This does not mean Kitty Thomson had no connections of this kind: she may, for example, have partnered a man on an adjoining plantation. But seeing her name alone is nonetheless suggestive.

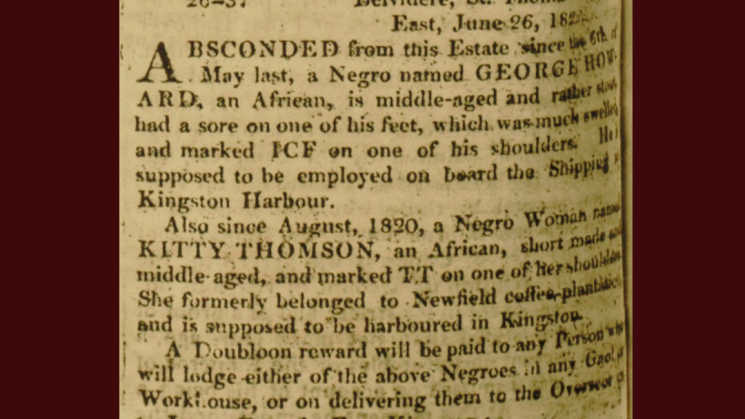

Five years would pass before Kitty Thomson’s name once again appeared. In July of 1822 an advertisement in the Cornwall Chronicle described and offered rewards for the capture and return of two enslaved people who had escaped from Belvidere. The short notice first described a male freedom seeker, then identified Kitty Thomson as having been absent from Belvidere since August 1820, a period of almost two years. The advertisement described her as “an African,” and mentioned that she “is supposed to be harboured in Kingston.” Home to the island’s largest free Black population, as well as many enslaved people, Kingston provided cover for a significant number of freedom seekers who were able to disguise their status. Perhaps, like other Jamaican freedom seekers, she sought out people who came from the same region and perhaps even the same African community as her.

The Jamaican slave code made clear that long-term escape was a serious offence, and enslaved people who escaped and remained free for up to six months would appear before two justices of the peace, and would likely be sentenced to be severely whipped, put to hard labor for three months, and even sold and transported off the island. Those freedom seekers like Kitty Thomson who were absent for more than six months would also appear before the justices, and “being thereof convicted, shall suffer death, or such punishment as the courts think proper to direct.” This was usually very severe whipping, bodily mutilation, or banishment and sale away from Jamaica. Long-term escape was defined by White law makers as rebellion, and it was punished as such.

One more record identifying Kitty Thomson has survived, the 1823 Slave Register for the parish of St Thomas in the East, held in the National Archives in Kew. Kitty Thomson’s name appears near the end of the listing of enslaved women and girls, and after her name she was described as “Negro” (which in this document appears to mean dark-skinned), African-born, and aged 33. But it is the final column that is most revealing. Labeled “Decrease and cause thereof,” the entries in this column record—for example—that the named person had been sold, or that they had died from maladies ranging from tetanus to dropsy to fever. The entry next to Kitty Thomson’s name reveals that she had been “Shipped of[f] country” by the slave court. Recaptured after being free for two years or more, Kitty Thomson had been brought before the slave court and sentenced to be transported and sold elsewhere, far from the plantation community and perhaps even family she may have had in Jamaica. Between 1807 and 1833 more than one thousand enslaved people were sentenced by Jamaican slave courts to be transported and sold elsewhere, and Kitty Thomson was one of them. Neither the slave court records nor the relevant shipping records survive, so we can’t be sure where Thomson was sent. However, most appear to have been sent to Cuban ports like Havanna, Trinidad, Bayamo, and Santiago de Cuba, and this was probably Kitty Thomson’s fate. Not only did she face a new enslaver language, culture, and religion, but she would have been entering a slave society containing a significantly lower percentage and number of people from her native West Central Africa. During the final twenty years of the legal slave trade about 14% of enslaved people brought from Africa came from Kitty Thomson’s region of birth, compared with nearly 25% in Jamaica.

Many of the challenges facing us in exploring Black agency in White archival records are illustrated by the few surviving records referring to Kitty Thomson. We know of her existence only through these documents created by enslavers or their agents. Such records defined her by obliterating her African identity, culture, and heritage, marking her with the initials of the White men who claimed ownership of her, renaming her, forcing her to work in coffee and then sugar production, and finally exiling her. How do we imagine the individual behind and beyond this violent reconstruction of her identity? Can we? The inner lives, the personalities, histories, and culture of African and African-descended people were obscured and deemed illegitimate and irrelevant in the surviving records. And yet there is an inherent tension inscribed in these dusty old White-created documents, for they all refer to her resistance. The first indicates that she had been placed in the workhouse for an unspecified offence, while others indicate that she had escaped and remained at liberty. In short, for all that the records indicate violent ownership and enslavement, they simultaneously reveal that Kitty Thomson constantly resisted her situation. Behind the short, cold words we can, perhaps, sense a powerful personality, a fierce and determined resistance to the objectification inherent in these records, and the enslavement that they described. This was a woman who rebelled time and time again, who freed herself for much of the period covered by these documents, and who was exiled from Jamaica as a result.

Scholars like Saidiya Hartman warn us that we can never presume to know enslaved people like Kitty Thomson. In her ground-breaking essay “Venus in Two Acts” Hartman write of another enslaved woman and observes that “One cannot ask, Who is Venus?” because it would be impossible to answer such a ques¬tion. How, Hartman asks, “can narrative embody life in words and at the same time respect what we cannot know? How does one listen for the groans and cries, the undecipherable songs, the crackle of fire in the cane fields, the laments for the dead, and the shouts of victory, and then assign words to all of it?” This is the challenge that faces us, to represent lives that can never be known, refusing to abandon them to the anonymity of White records, while acknowledging that people who were enslaved will always remain just out of our sight.

Marlon James’s novel The Book of Night Women imagines the complicated lives of enslaved women in eighteenth century Jamaica, and the ways in which enslaved women could imagine, discuss, and even plan resistance. Perhaps Kitty Thomson worked the provision grounds on the Belvidere Estate, planting foods she had learned to grow in Africa and talking with others who had come from her homeland and those born in Jamaica. As a historian I can imagine, but I can never know, why an African woman like Kitty Thomson resisted her enslavement so fiercely, and at such a high cost. When we examine the faded words we cannot fail to see the violent power of White enslavers in faded black ink on yellowed paper, but it is Kitty Thomson’s fierce independence and resistance that echoes loudest across the centuries.

[I am grateful to Professor Ebony Jones and Professor Diana Paton for their advice and insights]

Simon P. Newman

Fellow, Brown 2026, John Nicholas Brown Center for Advanced Study.

Honorary Fellow, Institute for Research in the Humanities, University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Sources

“KITTY, a Mungola,” The Cornwall Chronicle; and Jamaica General Advertiser (Montego Bay) October 14, 1816.

“ABSCONDED… Also since August, 1820, a Negro Woman named KITTY THOMSON,” The Royal Gazette (Kingston), July 13, 1822.

Return of slaves in parish of St Thomas, Jamaica in possession of Hon. George Cuthbert on 28 June 1820 as attorney of Mrs Stella Freeman and Philip Dormer Stanhope, proprietors of Belvidere Estate, Essex Records Office, Chelmsford, D/Dc F9/8.

Former British Colonial Dependencies, Slave Registers, 1813-1834, Jamaica, St Thomas in the East. The National Archives, T71/147. 1823. Page 129.

Slave Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database

Gwendolyn Mido Hall, “Bantulands: West Central Africa,” in Hall, Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 144-164.

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe, 12, 2 (June 2008), 1-14.

Marlon James, The Book of Night Women (New York: Riverhead Books, 2009).

Ebony Jones, “‘[S]old to Any One Who Would Buy Them”: Convict Transportation and the Intercolonial Slave Trade from Jamaica after 1807,” Journal of Global Slavery, 7 (2022), 103-129.