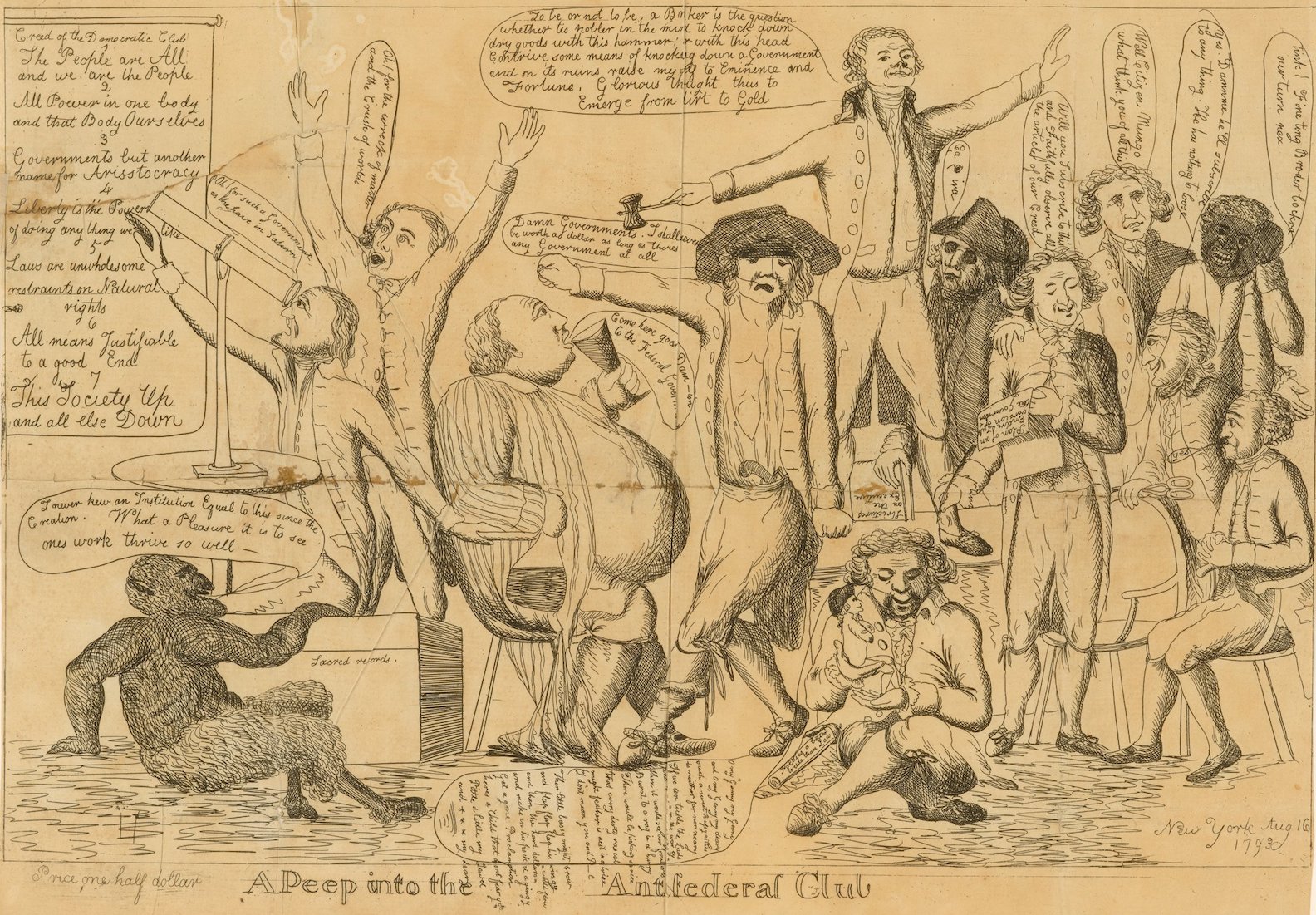

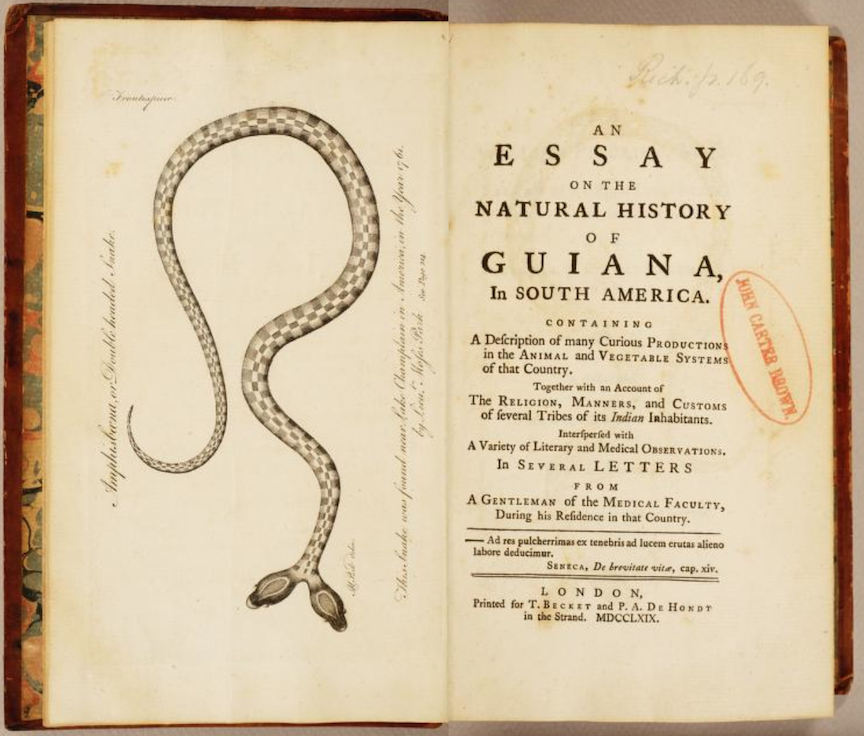

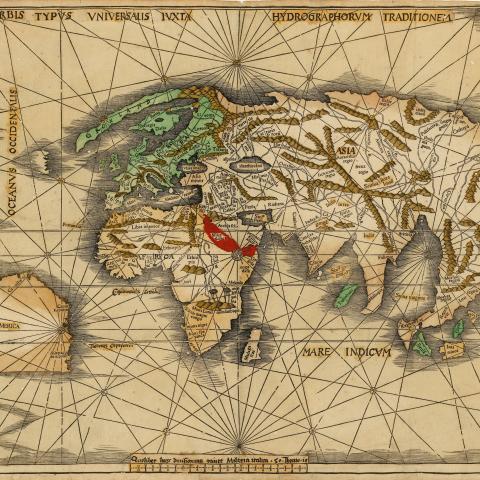

The Caribbean origins of Alexander Hamilton - and his contemporaries' connections to other parts of the globe – serve as the jumping-off point to retell an American story using the extraordinary collection of the John Carter Brown Library. Hurricanes and preachers, sugar plantations and the Federalist papers sit side-by-side with battle maps of Yorktown and the philosophical musings of the man from Monticello. All are here on display, enticing you back to the colonial Americas within the walls of the JCB, with the Marquis de Lafayette, Thomas Jefferson, and Hamilton as your guides.

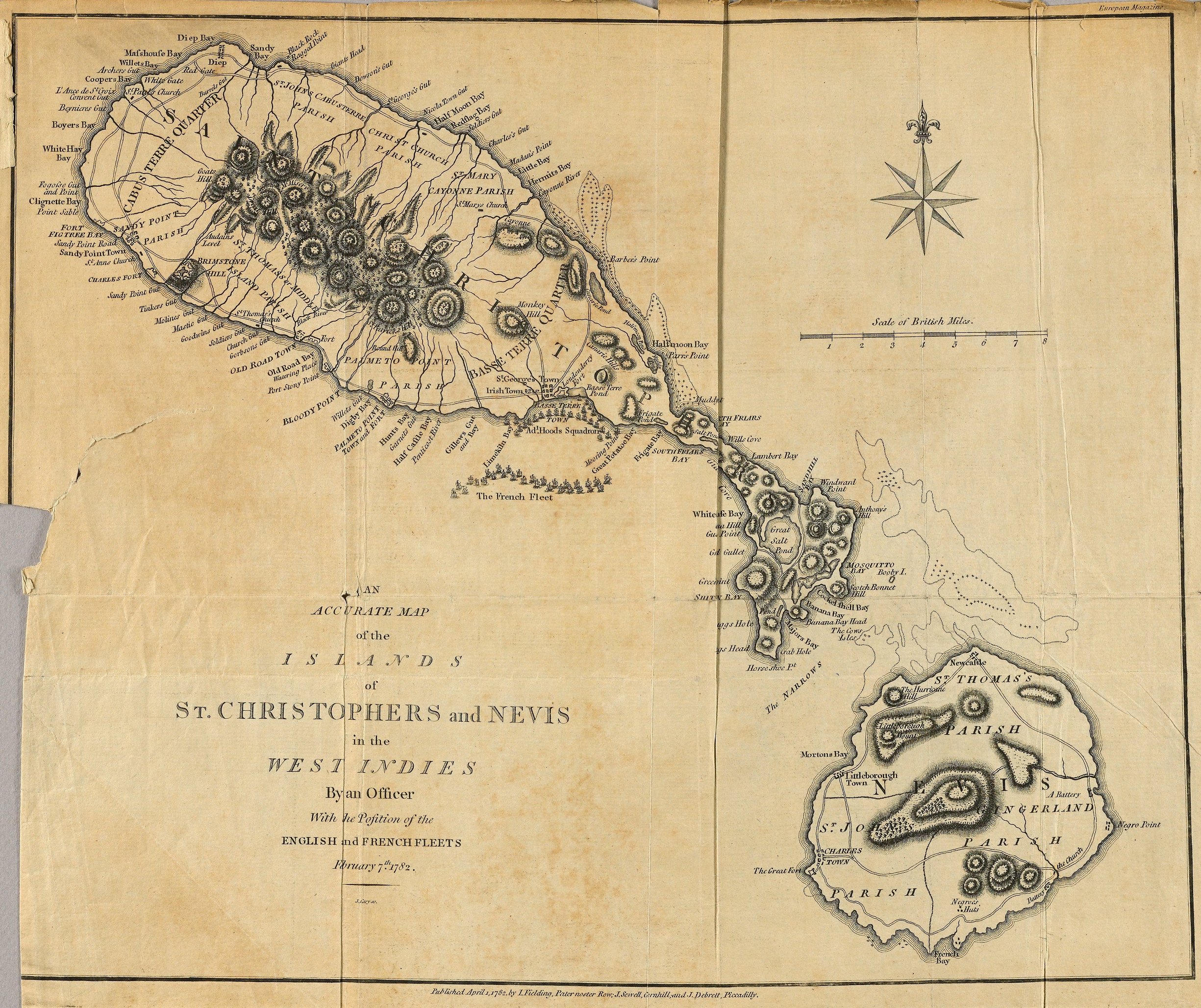

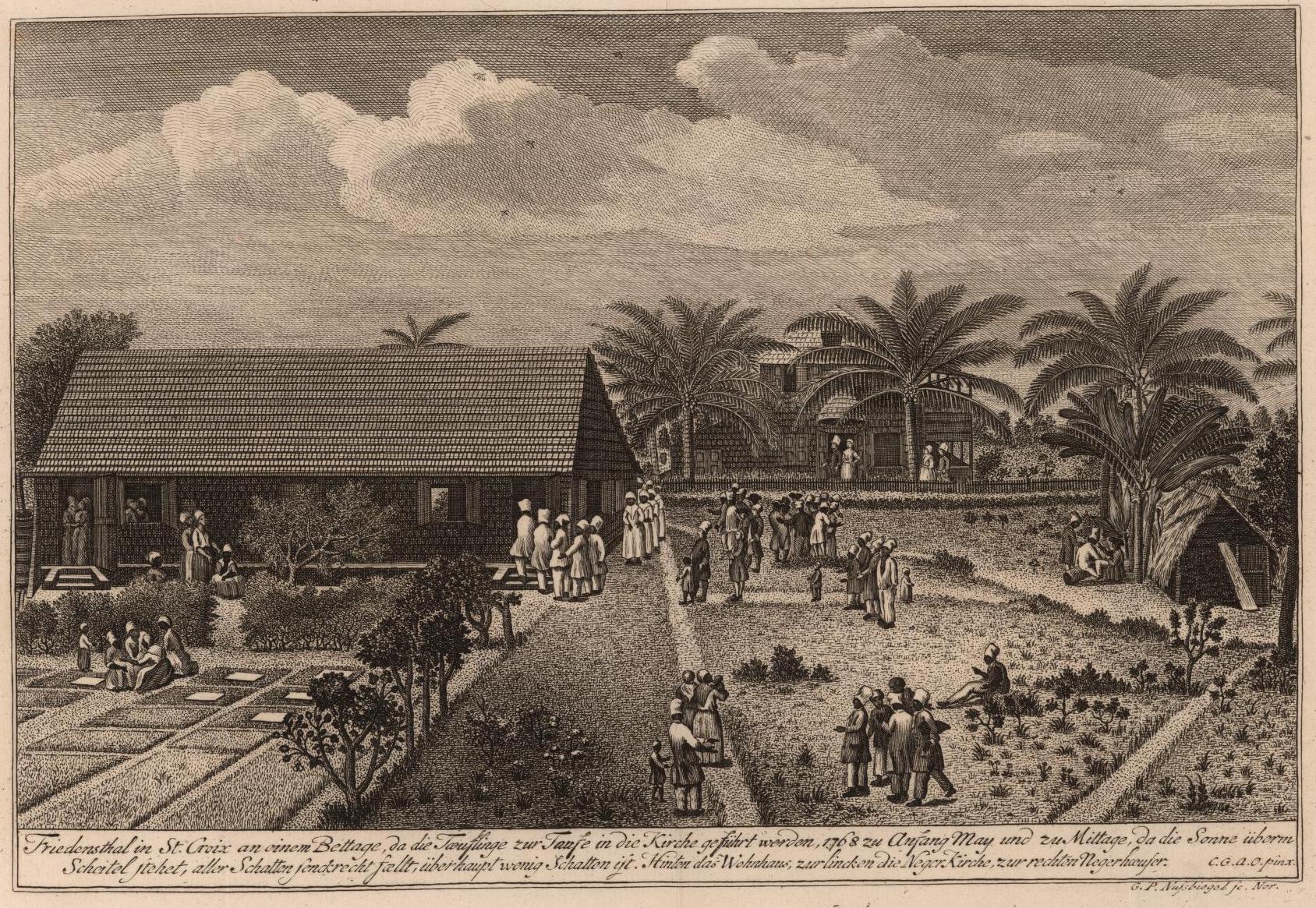

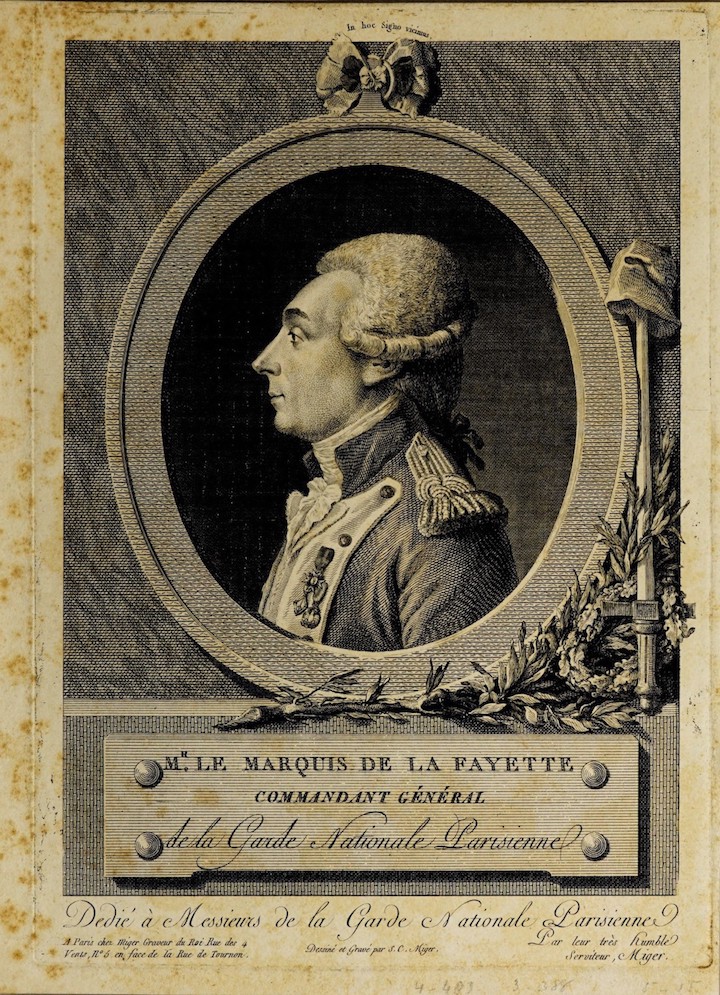

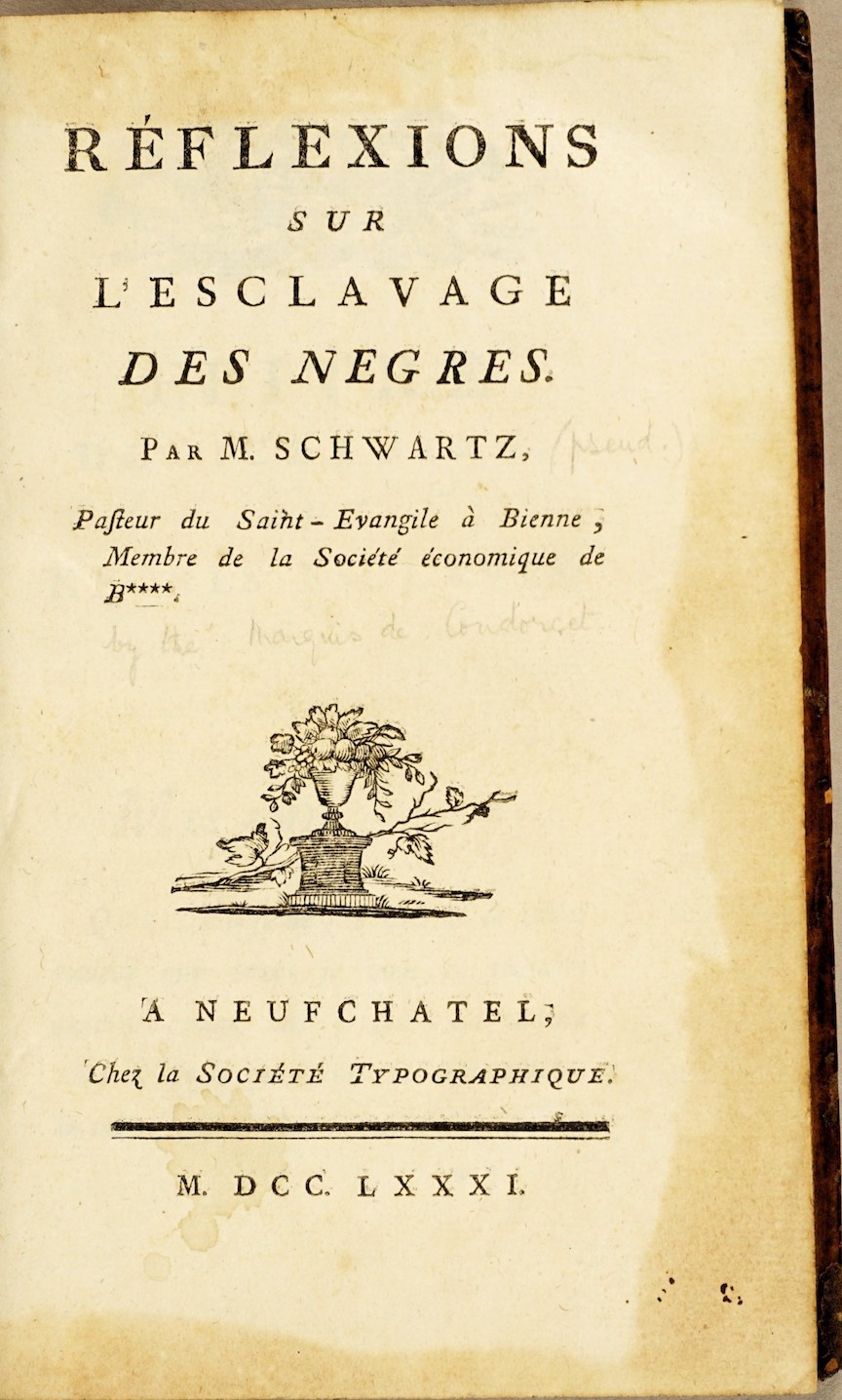

The title of this exhibition – “So what’d I miss?” – evokes the connections that scholars at the John Carter Brown Library piece together every day from historical materials in our collection. It refers to the hidden stories that lurk beneath the surface of the page and the missing knowledge that only assiduous researchers can bring to light: Alexander Hamilton’s humble Nevis origins; the Marquis de Lafayette’s interest in emancipating slaves in French Guyana; and Thomas Jefferson’s opposition to Haitian independence under black rule, despite his avowed opposition to slavery.

This exhibition – which in its original iteration honored Brown graduate Daveed Diggs ’04 and the entire cast of Hamilton: The Musical, celebrating the power of retelling history through the creative arts – connects the founding generation of the United States with its contemporaries across the Atlantic World, bringing Hamilton, Lafayette, Jefferson, and Bolívar together once again on the same revolutionary stage.

Credits

This exhibition was curated by JCB staff on the occasion of Brown University's 2017 Commencement.