Finding the Brown Brothers’ Sister in the Stacks; Or, a Tale of 4 Manuscripts on a Dark and Stormy Night

In the JCB’s collections are 4 manuscripts that have had very little if any use over the years they’ve reposed on our shelves in the library stacks. Not listed in our finding aid to the Brown Family Business Papers, the extraordinary manuscript collection at the library that documents an extended family’s merchant enterprises from the 18th through the late 19th century, nor in our online catalog, or in the card catalog except under their maker’s name, you’d almost have to know they’re there.

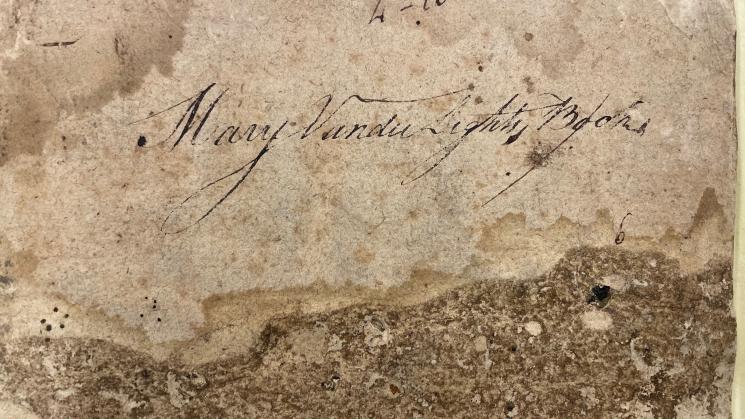

Or you’d have to stumble across them on a dark and stormy night, which is what happened to me. Last year a colleague and I were in the stacks rather late on a winter evening as some urgent repairs were being made to the library’s HVAC system. And, as one does, I was browsing. It’s a singular joy of my job to be able to explore the collections, though typically I venture into the stacks for research in the snippets of time between meetings, or in the course of discussions with colleagues about our JCB acquisitions or programs. As a specialist in 18th century British America, I’m always particularly curious about relevant materials. I had no idea when I pulled the first of these 4 items off the shelf, though, that I would be looking at something that would inaugurate a near-obsession, though given my career-long focus on women’s writing, I probably should have known the minute I saw the title “Mary Vanderlight’s Book.”

What I didn’t know that night, even once I started to look through that tantalizingly titled volume, and then through the other 3 on a shelf close by, was that Mary Vanderlight was Mary Brown Vanderlight, sister of the near-ubiquitous in the history of early Rhode Island and early American commerce, politics, and slavery Brown Brothers – Nicholas (1729-91), Joseph (1733-85), John (1736-1803), and Moses (1738-1836).

I’ve now written about Mary Brown Vanderlight in an essay for Commonplace, “The Brown Brothers Had a Sister.”

All I knew that night was that I was looking at three substantially-sized eighteenth-century accounts – and an estate inventory. I started right into reading the February 1755 “inventory of Druggs Belonging to the Estate of Doctor David Vanderlight.” It is a fulsome inventory, with items such as “myrtle,” “myrrh,” a version of arsenic, but also plenty of equipment, including bottles and “ointment pots,” boxes and cases, and tools including a “case of Pockett Instruments.” I’d read later that Vanderlight, a Dutch immigrant who arrived in Rhode Island by way of Guyana, was educated at the University of Leiden and was reputed the most educated man in mid-eighteenth Providence. Dr. Vanderlight’s inventory was taken by Benjamin Bowen (another doctor) and Nicholas Tillinghast.

When I turned to the 3 account books I realized that, as was indicated by the presence of Bowen and Tillinghast on the inventory, Vanderlight was connected to some of the early city’s most prominent and wealthy residents. He was treating the Governor, Stephen Hopkins; he was trading with the Brown family. But I also realized how brief Vanderlight’s residence in Providence must have been– and how short his marriage. And that he was married to Mary Brown.

The three account books cover the years 1751-55 thoroughly, but include entries up through the 1760s. Two are memorandum or day books, and one is a ledger; they represent different uses, or stages of accounting. In 2012 the JCB hosted an exhibit focused on the Brown Family Business Papers called “Mind Your Business” and in it, Kim Nusco, now the JCB’s Associate Librarian for Research and Reference, helpfully explained how a memorandum or day book as well as formal ledgers played a role in the double column accounting practiced by the Browns and others of the era. Each of the three show us clearly the customers or patients with whom David and Mary Vanderlight were doing business, and what they were selling in terms of goods and services.

In addition to the account books, little else is extant about Mary Brown Vanderlight in local archival materials, including at the JCB. From a small handful of letters sent to her, and bits and pieces of her accounts among those of her brothers, mother and other family members, I’ve been able to piece together a little more about Mary Brown Vanderlight’s life, and the context for the Brown Siblings as a quintet rather than a quartet. It’s clear that, like her mother Hope Power Brown and her famous brothers, she was financially capable as well as wealthy.

But she was clearly a reader– she was one of only two members of the library that was the precursor to the Providence Athenaeum– and yet we have no books that were definitively hers. She was clearly a writer, and yet we have no letters she wrote, no diary or journal. Just the accounts and a few other financial matters in her hand.

Piece by piece there will, I hope, be more to add. Mary Brown Vanderlight was, for example, a member of the Baptist Church like her mother, and unlike her Quaker brother Moses and Anglican brother Nicholas. Mary was noted in the church records as having only been baptized in late February of 1775, when she was over 40. I’ve learned a little more about where she lived, too. The home and shop she shared with David stood on the site of the current 19th century Superior Court building, between College and Hopkins Streets, “at the sign of the “Turk’s Head.” Mary’s brother Joseph Brown’s house would be built almost next door. (Though one of the most notable buildings in downtown Providence is the Turk’s Head, finished in 1913 and it was said– is often said on websites– that it was named for a shop with a Turk’s Head sign that stood on that site in the late eighteenth or nineteenth century. But the Turk’s Head was a pretty common sign in the early modern Atlantic World; in London alone there were dozens of coffeehouses and taverns by that name.)

Any history is the product of a patchwork of surviving information; for women or other marginal people we are working with lacey materials that show us, at best, fragments or moments of the past. That’s true for our contemporary period, but more so for centuries ago. Still, finding Mary Vanderlight in the interstices of a powerful family historical record shows us something about her, and about the world she lived in– and a lot about history itself.

In the next weeks we will be posting digital access to the four codices I came across on that dark and stormy night, and I hope lots of you will be encouraged to study them. I look forward to continuing to learn about Mary Brown Vanderlight and her world of mid- to late-18th century Providence and beyond.

Karin Wulf

Director and Librarian

The John Carter Brown Library

Professor of History

Brown University