In the early modern world, how did printed texts convey to European audiences ideas about race and indigeneity in the Americas? What methods, tropes and devices did they employ to introduce, transmit, and perpetuate ideologies? These are just some of the questions prompted by the exhibition Controlling Colonial Impressions: Representations of Race and Indigeneity in the Early Americas. Launched in conjunction with Brown University’s Sawyer Seminar on Race and Indigeneity in the Americas, this exhibition explores these topics through the medium of books, which became a primary vehicle for the dissemination of knowledge about the Americas to audiences in early modern Europe.

Curated collectively by undergraduate students in the History 1954J: History of the Book in the Americas course, it is organized thematically into four sections: Imagining and Imaging Colonial Subjects, an exploration of depictions of race and identity within the realm of the visual; ‘Objective’ Texts: Race and Indigeneity in Scientific Books, which examines the appropriation of science in the service of empire-building; The Iconography of Race in the British Atlantic, which treats race as a way of seeing; and Means of Control, a study of text as an instrument to assert power and dominance. Each section bears witness to conceptions of race in flux, tensions between the exotic and the recognizable, nearness and distance, as well as economic expediency and the erasure of identities.

Iconography of Race in the British Atlantic

Race can be a way of seeing, and racial imagery can both construct exploitative worldviews and free us from them. These books, written about the Americas for European audiences, deal with the shifting iconography of race in the Atlantic world. They demonstrate how writers and publishers deployed a balance of the familiar and the exotic befitting their interests in their depictions of race.

Rather than choose books with the most obvious racial caricatures that abound during this period, we have chosen to highlight slightly more nuanced, if no less insidious depictions of race. These three books demonstrate just as many ways of dealing with race in the context of colonialism. A briefe and true report disparages the culture of Indigenous peoples while elevating their bodies according to European standards. The Indian nectar deals with race and indigeneity through its conspicuous omission of the slave labor behind chocolate production. An Historical account of the black empire of Hayti inverts European norms by depicting formerly enslaved people as refined and French colonizers as barbaric and depraved, employing racist iconography of the savage in the process. These books demonstrate how European writers could draw upon familiarity and exoticism to shift the narrative of race and indigeneity according to their interests, thus shifting cultural interpretations of race itself.

How do we display these texts without recreating the racist tropes within? Do these texts leave room for “Indigenous survivance” or do they only reflect a European perspective? Who “owns” these texts?

Familiar Bodies, Exotic Culture

This report was compiled by Thomas Harriot and John White, leaders of the second Roanoke expedition of 1585, and first printed in London in 1588. Theodor de Bry published a 1590 edition in four different lan- guages as part of his Great Voyages series, entering the report into a global conversation around colonial speculation. The book promotes the British colonial enterprise in Virginia, advertising the agricultural potential of the land alongside an ethnography of its Indigenous inhabitants.

Significantly, de Bry substituted engravings for the watercolor paintings of the first edition. The engravings relate not only European interpretations of Roanoke and Indigenous culture, but also representations of race as mediated through a transatlantic network of printing. The classicized form of the “Coniuerer,” is belied by a frenzied pose that would have evoked pre-existing European associations between Indians and witchcraft. Here, racial difference is predicated on cultural, not physical characteristics. The engravings exoticize the actions of Indians as they simultaneously ground their bodies in familiar representations, revealing an environmental understanding of race. This worked in tandem with claims that Indians craved “the knowledge of the Gospel,” presenting them as ideal targets for Christianization.

Thomas Harriot, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia. Frankfurt: Theodor de Bry, 1590. Selected for this exhibition by William Evans.

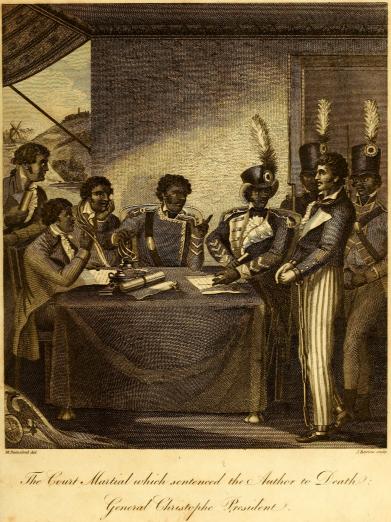

Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Iconography of the Haitian Revolution

Marcus Rainsford’s An historical account of the black empire of Hayti marks shift in the iconography of race in the colonial Caribbean. Rainsford, a British soldier who was forced ashore in Haiti and met Toussaint L’Ouverture while there, gives a relatively sympathetic account of the revolution and provides a guide for British colonial understanding of it. This book comes from a colonial perspective, so the tone is both paternalistic and analytical, seeking to direct the British Caribbean colonies so as to avoid the fate of Haiti (and demonize the French, who the British were fighting a war against).

The graphic etchings at the beginning of this book are one of its most striking features. It’s important to note that Rainsford depicts wartime cruelty and death on both sides. However, it’s the French that are the truly barbaric ones — they are depicted as letting bloodhounds attack civilians, while L’Ouverture is given a dignified portrait and his correspondence is reprinted in facsimile. By juxtaposing the poise and courage of the Haitians with the barbarity and depravity of the French, the Historical account flips the stereotypical racial imagery on its head.

Marcus Rainsford, An historical account of the black empire of Hayti. London: James Cundee, 1805. Selected for this exhibition by Harold Triedman.

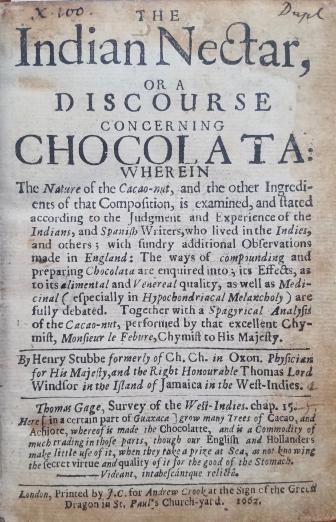

Neglecting Race in the Chocolate Trade

Chocolate is a popular treat around the world today, but 400 years ago, it was an important component in Native American culture and consumed commonly by Indigenous people. The Indian nectar is written for Europeans who may not have known about cacao by taking a scientific approach to the examination of chocolate. The author breaks down the composition of the cacao nut and demonstrates its medicinal benefits, which, at the same time, creates a lens through which Europeans could find familiarity in this Indigenous commodity.

This book paints chocolate as a miracle substance, constantly drawing upon its “unquestionable nourishment.” By the end of this book, readers would have been left with an even greater curiosity about chocolate and perhaps a desire to acquire some for themselves, which would directly contribute to the growth of Britain’s economic interests in the Americas. However, it never addresses slavery or the brutality of cacao extraction. This book, ultimately being an elaborate advertisement for trade with the New World and further colonization, demonstrates how Europeans were attracted to the exotic elements of Native culture but neglected to understand the realities of Native life.

Henry Stubbe, The Indian nectar, or A discourse concerning chocolata. London: James Cottrell, 1662. Selected for this exhibition by Zoe Zimmerman.

"Objective" Texts: Race and Indigeneity in Scientific Books

In the JCB there are many texts which claim scientific objectivity. For many Europeans, The New World was viewed as a place of experimentation, innovation, and technological advancement. Through books such as the ones presented here, doctors and naturalists disseminated medical and scientific knowledge, often for the express purposes of the Crown. These books observe a wide range of geographic focus and topical material, from the Caribbean to Brazil, medicine to farming.

It is irresponsible, however, to talk about these “objective” texts without contextualizing them with issues of race and indigeneity. This is perhaps most evident in texts like Practical rules for the management and medical treatment of Negro slaves, in the sugar colonies, where slavery and medical advancement come hand in hand. In others such as O fazendeiro do Brazil or Tratado sobre la fiebre biliosa y otras enfermedades, links to colonialism are less explicit but no less present.

The urgency of this topic is therefore not anchored in the past; rather, in engaging explicitly with their material and contextual histories, the books presented here carry critically into the current moment, exposing the exploitative mechanisms inherent in otherwise ostensibly impartial subjects.

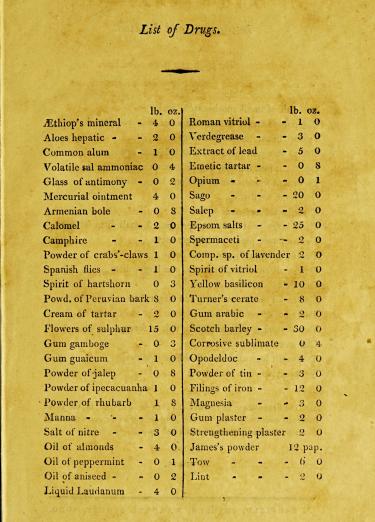

I have frequently departed from the rules laid down by European practitioners

In the early nineteenth century, a series of treaties and laws put an end to the international slave trade. With the cessation of the importation of new slaves came an increased interest in slave medicine, as plantation owners sought to maintain and eventually expand the number of enslaved workers they had available. Practical rules for the management and medical treatment of Negro slaves, in the sugar colonies anticipated this trend. Written by Dr. David Collins, a medical expert as well as a planter, the text contains a wide variety of descriptions of treatments, recipes for medicines, and other medical advice for the treatment of slaves.

The pages on display show a list of drugs and medical treatments that Dr. Collins recommended planters keep on hand at all times. Here we see a mix of European treatments (laudanum, mercury, James’s powder), treatments originally used by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas (Peruvian bark, powder of ipecacuanha), and new or more experimental concoctions (some of Collins’ “Compositions”). Indigenous or untried remedies were often tested and used on slaves before they were accepted into wider medical use.

A Professional Planter [= David Collins], Practical rules for the management and medical treatment of Negro slaves, in the sugar colonies. London : J. Barfield, 1803. Selected for this exhibition by Nathan Allen.

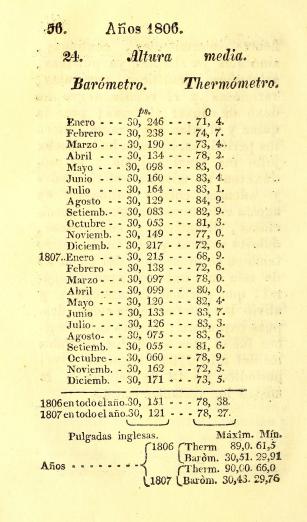

Le quitaron la vida

Marcos Sánchez Rubio was one of the most prolific and respected doctors in nineteenth century Cuba. This text, one of his more famous works, is a scientific examination of causes and treatments for a myriad of diseases. With both numerical calculations of weather as well as intimate patient portraits, the book is an example of a high caliber medicinal book.

Rubio’s observations of an enslaved woman suffering from tetanus (displayed here), however, illuminate the more insidious side of his work, namely the ways in which this ostensibly benevolent history of medicine – of understanding, isolating, and ultimately curing disease – is embedded unmistakably in a larger context. “Le quitaron la vida,” Rubio ends his observations. “They took away her life” for stealing candles. This, for the doctor, is a victory; at least she did not die of tetanus.

Comparing the contrast between the historical violence inherent in his observations about the enslaved woman with his almost aggressively objective observations about the weather (pictured here) shows an insidiously equalizing regime reducing her experience to a statistic.

Marcos Sánchez Rubio, Tratado sobre la fiebre biliosa y otras enfermedades. Habana, Cuba: En la imprenta del Comercio, 1814.

Cataloging Labor and Bodies

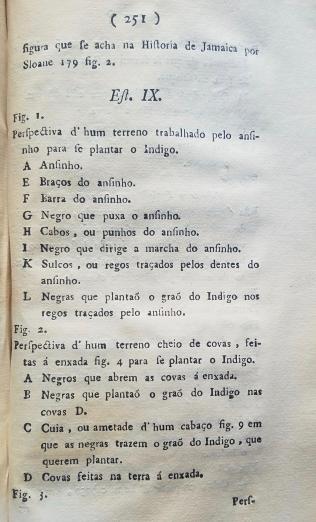

O fazendeiro do Brazil (The Brazilian Farmer) was a compilation edited by Friar José Mariano da Conceição Velloso for the purpose of the colony’s economic development. Multiple volumes covered the production of spices, textiles, and dyes using a series of reports and articles translated from other sources into Portuguese. Velloso would eventually accompany the Portuguese royal family back to his native Brazil in 1807 when the Crown moved to Rio de Janeiro following Napoleon’s invasion in Europe.

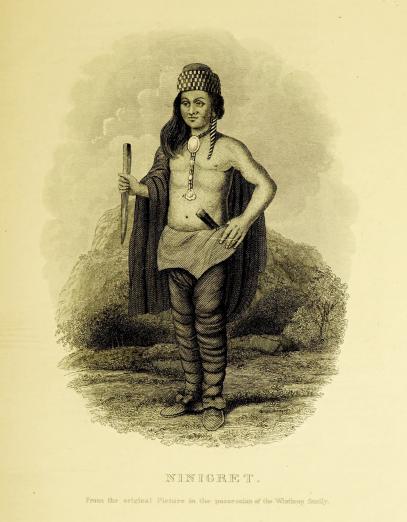

While ostensibly a purely scientific work, O fazendeiro plays an interesting role in codifying labor across lines of race, class, and gender. The annotations shown here accompany an engraving discussing the planting and harvesting of indigo as a dye—men (negros) and women (negras) can be distinguished both by their appearance and the text’s annotations, delegated to different agricultural roles throughout the process. Are these people enslaved? How is agency partitioned when black bodies are indexed next to common tools like the hoe and the plow?

José Mariano da Conceição Velloso, O fazendeiro do Brazil. Volume 2, part 2. Lisboa: Na Regia officina typografica, 1800. Selected for this exhibition by Mark Liang.

Imagining and Imaging Colonial Subjects

In this section of the exhibition, we turn to illustrations of Indigenous peoples conceived and created by European colonists and illustrators, examining them as signifiers of popular conceptualizations of, and attitudes towards, indigeneity. These images ask us to reflect upon racial and cultural transformations throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Was race an immutable category, or one that could be changed and transgressed through various aesthetic shifts?

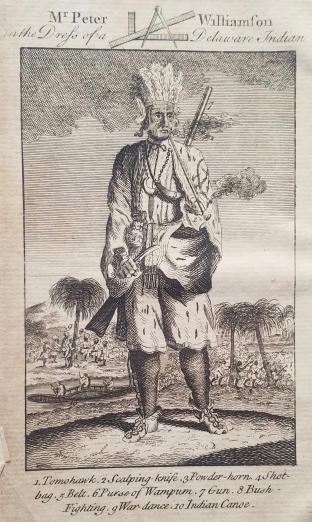

A special illustrated 1864 copy of an Increase Mather work reflects the heroization of two notable Indigenous leaders in American society. A Primer for teaching literacy in Mohawk and English, as well as promoting Christian beliefs, shows a schoolhouse where both Indigenous and European imagery is employed. Peter Williamson’s captivity narrative, French and Indian Cruelty, contains an illustration of Williamson in “Indian” garb. A somewhat faithful indicator of the costumed performances he staged as a curiosity in taverns and coffeehouses, this frontispiece asks of us profound questions of identity: what bearing does this assumed persona have on his identity? All three books invite us to grapple with complex questions of identity, reception, and remembrance, questions remaining with us today.

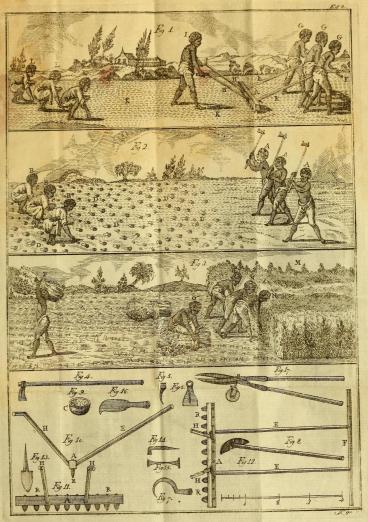

Literacy and Colonialism

A primer for the use of the Mohawk children opens with an engraving by Englishman James Peachey of an Indigenous, presumably Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk), teacher sitting before his pupils. He wears European-style breeches and coat, and traditional earrings. On the desk behind him lie a book, a quill, and an ink bottle. The children all hold their own small books, presumably the primer itself.

The picture shows the purpose of the primer: to impose European notions of literacy onto a culture with very different means of record-keeping. Most of its pages are dedicated to Biblical education as well as English/ Mohawk literacy, showing the role of Christian missionaries in colonization. The blend of dress may suggest a deliberate resistance to these changes, an attempt to maintain Kanien’kehá:ka identity under colonial rule.

Daniel Claus, A primer for the use of the Mohawk children = Waerighwaghsawe iksaongoenwa. Tsiwaondad-derighhonny kaghyadoghsera. London: C. Buckton (1786). Selected for this exhibition by Caroline Mulligan.

Memory: Indigenous Subjects of Engravings

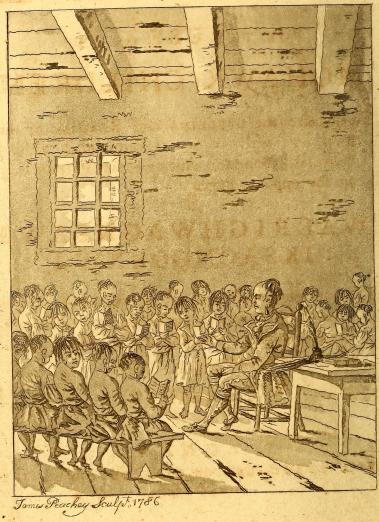

King Philip (or Metacomet) was the leader of the anti-colonial force in the 1675-1676 war that now bears his name. This image of Metacomet was first engraved by Paul Revere for the second edition of Benjamin Church’s Entertaining History of King Philip’s War (1772), and was reprinted many times in the next three centuries.

This particular copy is extra-illustrated with 27 tipped-in engravings, chosen by John Carter Brown; of those images, only two are of Indigenous men; the other image is of Ninigret, sachem of the Nehântick. Most depictions of Indigenous peoples in eighteenth and nineteenth-century printed materials are fictionalized, with very few persons specifically named.

The fact that Ninigret and Metacomet are named subjects of engravings, along with Brown’s inclusion of them in his specially-bound copy, speaks to elite Americans’ fascination with the two men as heroic figures.

Increase Mather, Samuel G. Drake (ed.), The Early History of New England. Boston, 1864. Selected for this exhibition by Sean Briody.

Performing Indigeneity: Peter Williamson's French and Indian cruelty

Histrionic, mercurial, and frequently violent, French and Indian cruelty is Peter Williamson’s autobiographical account of his multiple kidnappings: first at the hands of an Edinburgh merchant, who forces him into indentured servitude; then by a band of Delaware Indians; and finally, French troops imprison him during the Seven Years’ War. As its title suggests, the narrative is replete with details of gore, horror, and hardship. Notably, however, much of Williamson’s narrative is demonstrably false. It appears the impoverished author fabricated large segments of his tale in a ploy to sell copies: cognizant of the allure of the theatrical and the exotic, Williamson knew the more fanciful his tale, the more it would appeal to a British audience.

The book’s frontispiece attests to the performative aspects of Williamson’s narrative and persona. Citing in its figuration both the frontispiece to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and a widely circulated illustration of a Mohawk warrior, it depicts Williamson in “Indian” dress: he dons an elaborate feathered headdress, wears moccasins for shoes, and brandishes a tomahawk. This tells us a great deal about the proclivities of the English audiences who consumed Williamson’s tale: they wanted a tangible yet familiar image of the Native.

Peter Williamson, French and Indian cruelty. London: printed for the unfortunate author, and sold by R. Griffiths, 1759. Selected for this exhibition by Tobias Berggruen.

Means of Control

Under imperial bureaucracies, written records preserve debates about the legal and moral practice of colonial rule, as well as the structures through which colonial rule was imposed and colonial regulations implemented. These practices ranged from religious evangelization to legal proceedings, impacting the daily lives of Indigenous, enslaved, immigrant, and Creole populations across the Americas during the period of European colonization. The three volumes shown here record different aspects of colonial regulatory systems, aimed at different populations in different parts of the Americas and during different time periods. Together, they illustrate the broad reach of regulatory systems in the American colonies.

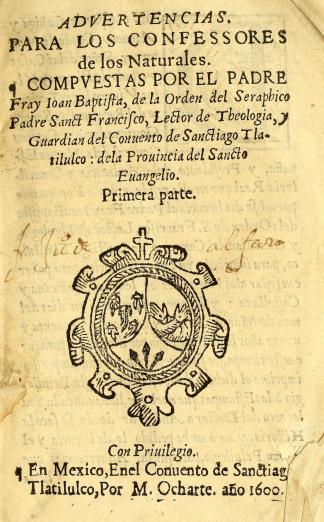

The earliest book in this collection, the Advertencias para los confessores (Notices for Confessors) is a handbook for Spanish missionaries. Written in Spanish, Latin, and Nahuatl, the volume seeks to navigate the shifting theology of Catholicism across cultures and languages. Bridging the gap between religion and the law, De justitia & contractibus […] libri septem (Seven Books on Justice and Contracts), contains a theological discussion of – and moral justification for – the slave trade. The final document, a set of letters written by the Bishop of Tucumán (Argentina) upon news of the rebellion of Tupac Amaru in Peru, demonstrates not only how Indigenous groups rebelled against colonial rule, but how factions within Spanish America sought to use this information for their own political purposes. Together, these documents show how religious and legal discourses regulated the lives of Black and Indigenous subjects on which the colonies depended.

Religion and Conversion

Spanish missionaries in sixteenth-century Mesoamerica used education as part of evangelization. Through books like this confessional manual, printed at the Franciscan convent in Tlatelolco, they instructed new missionaries on religious practice in the colonies. Printed in a pocket-size octavo for easy consultation, the Advertencias has numerous errors, like the two folios numbered 14 (shown here).

By regulating religious practice in the Americas, books like the Advertencias illustrate Spanish ideas about Indigenous culture and language. On the page shown here, the author explains that Indigenous penitents do not confess properly. For example, he says, they are more likely to say the Nahuatl “aço Pedro momecatitinemi” than the Spanish “Pedro esta amancebado.” Both phrases mean the same thing: that Pedro is in a relationship with someone who is not his wife. But the less definitive phrasing used in the Mesoamerican language Nahuatl is enough to make the Indigenous confession suspect.

The Advertencias is bound with the more celebrated Confessionario (1599) in a modern binding, with ownership marks of Nicolas León and the Colegio de San Gregorio, Mexico.

Juan Bautista, Aduertencias. Para los confessores de los naturales. Tlatelolco: M. Ocharte, 1600. Selected for this exhibition by Hannah Alpert-Abrams.

Letters that controlled Opinion against colonial rule

Chocolate is a popular treat around the world today, but 400 years ago, it was an important component in Native American culture and consumed commonly by Indigenous people. The Indian nectar is written for Europeans who may not have known about cacao by taking a scientific approach to the examination of chocolate. The author breaks down the composition of the cacao nut and demonstrates its medicinal benefits, which, at the same time, creates a lens through which Europeans could find familiarity in this Indigenous commodity.

This book paints chocolate as a miracle substance, constantly drawing upon its “unquestionable nourishment.” By the end of this book, readers would have been left with an even greater curiosity about chocolate and perhaps a desire to acquire some for themselves, which would directly contribute to the growth of Britain’s economic interests in the Americas. However, it never addresses slavery or the brutality of cacao extraction. This book, ultimately being an elaborate advertisement for trade with the New World and further colonization, demonstrates how Europeans were attracted to the exotic elements of Native culture but neglected to understand the realities of Native life.

Cartas que escribio, con ocasion de la derrota del rebelde Tupac-maro. Buenos Aires: Real Imprenta de los Ninos Expositos, 1781. Selected for this exhibition by Neil Safier.

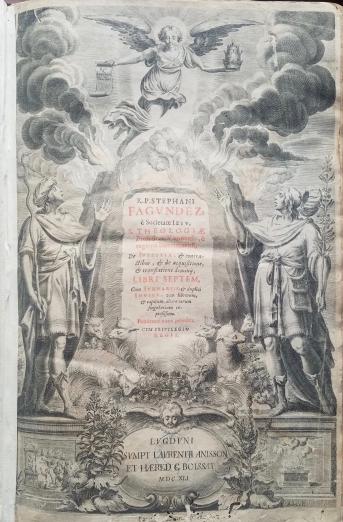

Justifying the slave trade

The Iberian slave trade, responsible for the displacement and sale of millions of Africans as slaves to the Americas, was not only driven by European capitalist and imperial ambitions. Since the sixteenth century, Catholic theologians writing on the moral conditions of economic realities started to include chapters justifying the slave trade.

This publication on the fairness of contracts, acquisitions, and possessions, written by the Portuguese Jesuit Stephanus Fagundez (1577- 1645), fits in a tradition of Catholic legal experts who not only failed to condemn the slave trade on moral grounds, but who accepted the slave trade as an economic reality and focused on how and when slaves could be sold legally.

Drawing from Aristotle, civil and canon law, and the Holy Scriptures, Fagundez argues that the sale of a human should be legal when one was captured in a just war, had committed certain crimes, or was born in slavery. Scholars like Fagundez facilitated the slave trade further by stating that it was not the responsibility of the slave trader to check the legality of a sale in case of doubt and that testimonies of the enslaved were not accepted as evidence in these cases.

Stephanus Fagundez, De justitia, & contractibus, & de acquisitione, & translatione dominii, libri septem. Lyon: Laurent Anisson, 1641. Selected for this exhibition by Stijn van Rossem.

Related Events

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

Credits

This exhibition was collectively curated by students in the Spring 2019 course "History 1954J: History of the Book in the Americas": Nathan Allen, Tobias Berggruen, Sean Briody, William Evans, Mark Liang, Caroline Mulligan, Jamie Solomon, Harold Triedman, Zoe Zimmermann.