The early modern period (1500-1800) was an age of maritime empire, associated with ships plying oceans and fierce struggles for control of the world’s sea lanes. But seas, and bodies of water more generally, served multiple purposes beyond their transformation into highways of exchange. They functioned as waterways that transported people, ideas, bacteria, and commodities both locally and across the globe. They served as a tool for thinking about the changing nature of the world. And they allowed people to think about the composition of the human body, its capacity for work, and the types of relationships that people forged with one another on and off land – on maps, in treatises, in private letters and in intricate projects of colonial construction.

Long before French writers surveyed the Mississippi, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan – seat of one of the greatest American empires –flourished in a lacustrine matrix expertly elaborated by the Mexica. This exhibition explores the many ways in which water - from the five interconnected lakes of what would become Mexico City to the five Great Lakes of New France - touched people’s lives, even those who never set foot on a ship or visited a port town. On the prow of a ship or as a conduit for knowledge about the globe, water shaped encounters both real and imagined, in the early modern Americas and far beyond.

French writers on American waters

When early modern French writers encountered American waters, they marveled at their scale: many early accounts insisted on the enormity of American rivers and lakes, and although they sometimes suggest that the bodies of water they encountered in the Americas could be understood in relation to ones they knew at home – the Seine was frequently used as a comparative unit of measurement – they also found that their narratives floundered as they encountered these new bodies of water. To find their way through this new waterworld, French writers came to observe indigenous techniques and vocabularies with particular care.

Where some French accounts suggested the commercial and pleasurable potential of American waters, others worried over their disastrous potential for European projects in the New World, returning constantly to the difficulty of navigating in dangerous new conditions. This concern led to a real admiration for the indigenous construction and navigation of canoes and pirogues; even writers who scorned other indigenous practices regarded indigenous waterway techniques in a different light. The observation of this local, technical knowledge called for new water vocabularies, central to the cartographic and other projects of French explorers.

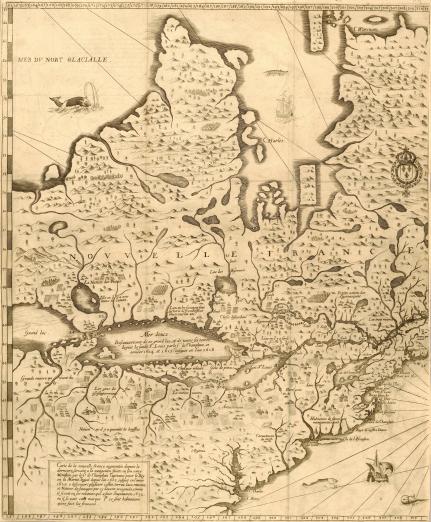

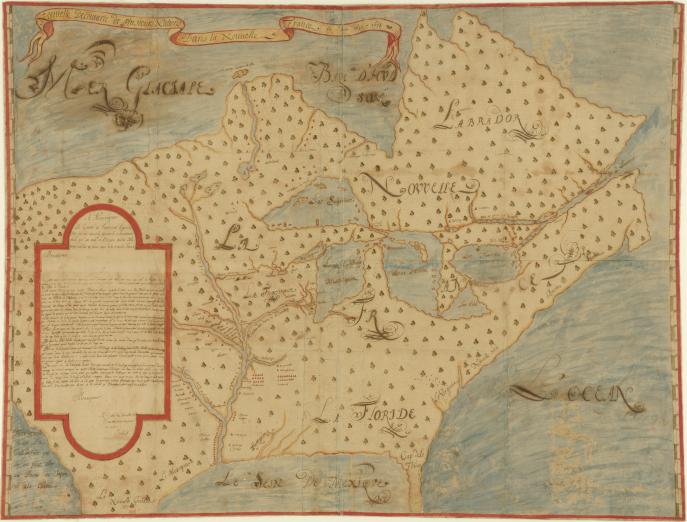

Samuel de Champlain, "Carte de la Nouvelle-France, augmentée depuis la dernierem servant à la navigation faicte de son vray meridian...," 1632

This extraordinary 1632 rendering of various bulbous bodies of water was the first to show European exploration west of Montreal, and to set out the network of the Great Lakes, a complex connection of water and land that a contemporary writer described as an “assemblage.” This is the first cartographic depiction of Lake Superior. The map carefully records the various incursion of Champlain and the supposed “settlements” made by previous French expeditions. In the surrounding seas, boats and bodies of whales look on.

Joliet, "Nouvelle Decouverte de plusieurs nations dans la Nouvelle France en l’anné 1673 et 1674," 1674

Joliet’s exploration of the Great Lakes and Mississippi had, this map tells us, been blessed by happy luck. He has escaped all danger and crossed forty-two rapids and seen wonders along the way; he describes seeing the beautiful banks of the great river, its fruit trees, and the watermelons taken for refreshment in lands too hot to know ice. But 15 minutes away from his return home to Montreal, in sight of French settlements, his canoe flipped and he lost all his papers to the waters. All that remained to him was his life, he notes, and fortunately also his memory: this map was made by memory shortly after the accident.

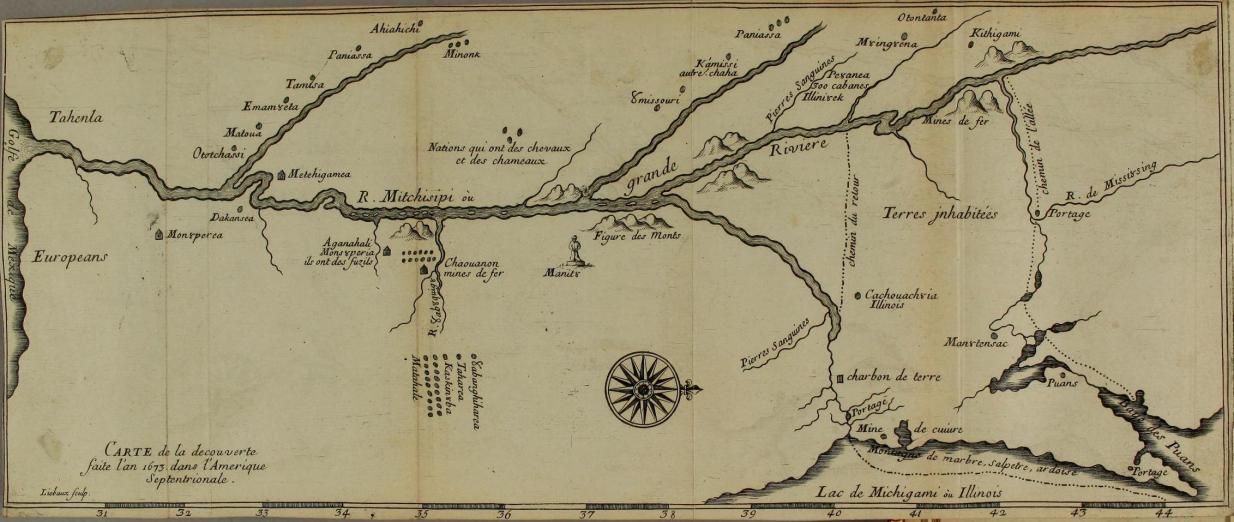

Jacques Marquette, "Carte de la decouverte faite l’an 1673 dans l’Amerique septentrionale I in Melchisédec Thévenot, Recueil de voyages, "[1681]

This map looks remarkable different from that of Joliet, but it stems from the same journey, and was originally drawn by the Jesuit Jacques Marquette. Here Marquette reduces the represented journey to the essential line of the Mississippi, so that the purpose and narrative of the journey is clearer.

Louis Hennepin, "A new discovery of a vast country in America, extending above four thousand miles, between New France and New Mexico;….," 1698

In this earliest printed account of Louisiana, Louis Hennepin, a Franciscan from the Spanish Netherlands, presents his discovery as a penetration of the pleasures of the new world. Hennepin had published an earlier text on the Mississippi dedicated to the French king Louis XIV; this one, a few years later, is for his great rival William of Orange, and Hennepin takes pains to distinguish his two works by claiming that this one sets out the knowledge of the whole length of the Mississippi. Here that river unfurls easily and deliciously as we open the book, with each canoe rounding the bend seeming to presage his easy passage – although in fact Hennepin enjoys recounting his narrow escapes from disaster. (This is the English translation of the original French edition, also shown here.)

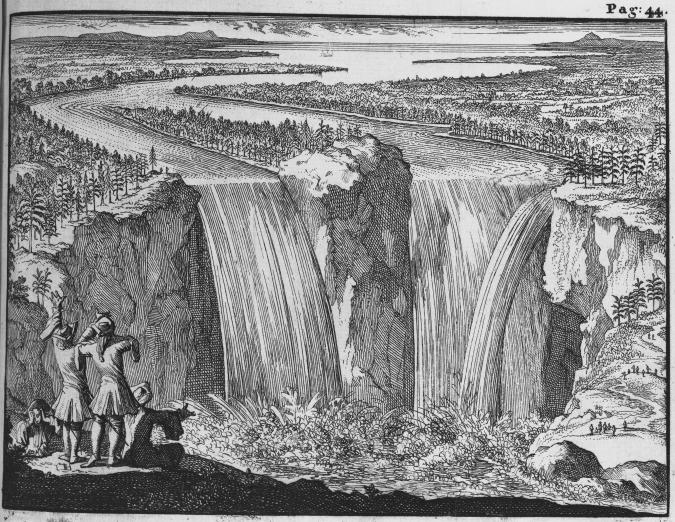

Louis Hennepin, "Nouvelle docouverte de’un tres grand pays situé dans l’Amérique, entre le Nouveau Mexique, et la mer glaciale...," 1697

Hennepin’s waters were not always as peaceful as those shown in the frontispiece. He was the first European to write about Niagara Falls, describing European waterfalls as “meagre samples” in comparison; this image, made from Hennepin’s drawing, is the first published plate showing them, and for decades after images of the Falls were based on this. Notice the little figure at bottom left, with his hands over his ears; Hennepin wrote that the water was louder than thunder, and that its bellowing could be heard for fifteen leagues around. The verb “mugir,” to bellow, is striking since Hennepin also insisted on the water’s capacity to destroy any animal that happened to graze nearby. His description of the Falls strongly recalls European accounts of monsters.

Claude Le Beau, "Avantures du Sr. C. Le Beau, avocat en parlement, ou Voyage curieux et noveau, parmi les sauvages de l’Amérique, septentrionale...," 1738

European writers were not interested only in human techniques for handling water: American animals were also objects of much marvel. Claude Le Beau is like a figure from eighteenth-century fiction: transported as a prisoner to Canada, probably for the crime of libertinage, his ship was wrecked off the shore of Québec and he was saved (although later hung in effigy for having run away). His adventures borrowed heavily from earlier writers and were frowned upon as “novelistic” but are enormous fun to read. Le Beau claimed to have worked in Québec’s Bureau du Castor (Beaver Office), and the most original part of his text describes the habits of beavers, here shown swimming in formation to escape hunters with guns. Le Beau takes great pleasure in their agility and their deployment of materials, and describes their skill and strength; perhaps, as someone who’d himself escaped by water, he had a particular interested in this scene.

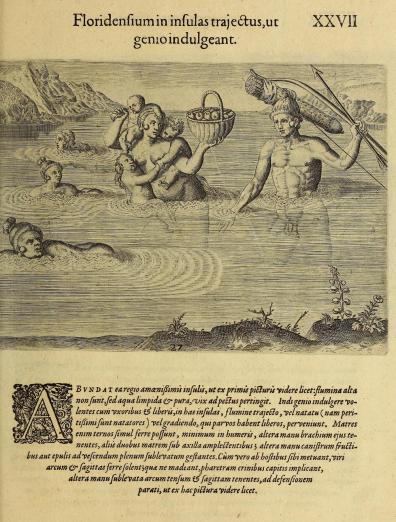

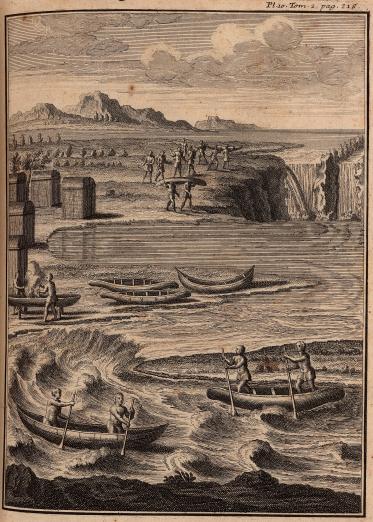

Theodore de Bry, “Floridians Crossing Over to an Island to take their Pleasure” in Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, "Brevis narratio eorum quae in Florida Americae provi[n]cia Gallis acciderunt...," (1609?)

This is one of a series of plates by Theodore de Bry stemming from the drawings made by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, the official artist of the briefly-lived French Protestant colony in Florida (1564-5). These images depict the practices of the local Timucua people; in contrast to many later depictions of American waters, here De Bry shows indigenous people using the water for pleasurable pursuits. The text describes the scene as a family picnic, praising the Timucua as “excellent swimmers”; yet despite the pleasurable setting, the man carries a quiver of arrows on his head, just in case. It is unusual in European depictions of this period to see beneath the water; here, what lies beneath is the tantalizing nudity of the Timucua.

Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce Lahontan, "Nouveaux voyages de Mr. le baron de Lahontan, dans l'Amerique Septentrionale...," 1703

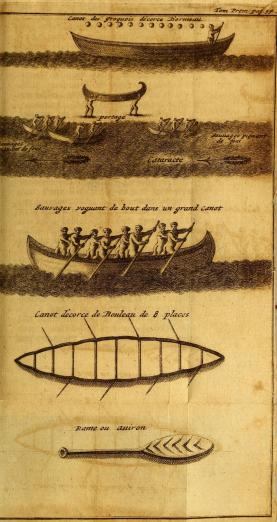

The Baron de Lahontan had served in the French military in the upper Mississippi valley, and his accounts, mingling fact and fiction, were key to the establishment of the figure of the “noble savage.” Here he gives an “ample description” of the bark canoe of the Iroquois, with such specifications about design and construction that the reader is almost invited to make one at home. Lahontan describes the smallest canoes as “death traps,” but he shows how the different positions taken by the skilled canoeists – here shown standing – enable them to navigate in very different conditions.

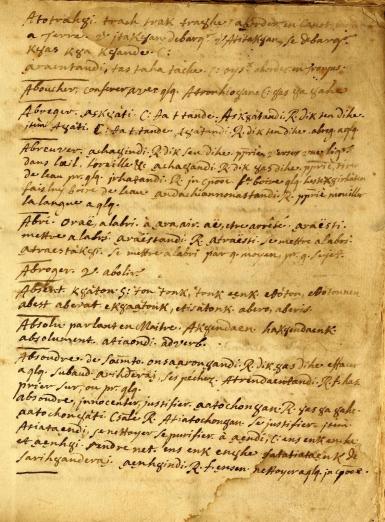

Pierre Joseph Marie Chaumonot, [French-Huron dictionary and vocabulary], 1640-1693

This fragile bundle is a French-Huron (Wyandot) dictionary from the late seventeenth century, probably compiled by the Jesuit Pierre-Joseph-Marie Chaumonot. The dictionary’s headwords are all in French, apart from the opening term: atotrahzi, to get into a canoe on the shore. The dictionary drips with specialized vocabularies for water and watercraft, suggesting something of the complex watery world the Jesuits were trying to understand; at the end it gives clusters of related terms. Here we see the entry for canot (canoe), with many subheadings: bark canoe, stitching the canoe, the canoe is taking on water, navigating the canoe, escaping from the canoe, and so on.

Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce Lahontan, "Nouveaux voyages de Mr. le baron de Lahontan, dans l'Amerique Septentrionale...," 1703

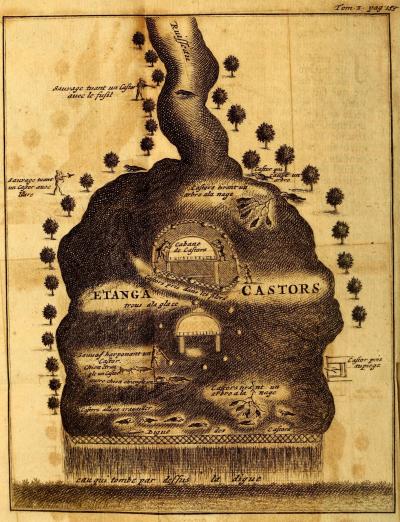

Lahontan, like Le Beau and many other French writers, was not only interested in human techniques for handling water. He also describes the skill and artistry of beavers as navigators and managers of water, noting that he knows many men with not one hundredth of their intelligence. The story of the political life of beavers and their Republics, was often told in eighteenth-century texts, but Lahontan and others also depicted the battle between human and animal intelligence in extraordinary images like this one of a beaver pond, showing beavers in freedom (pulling trees across the water) and in defeat (caught in nets and traps).

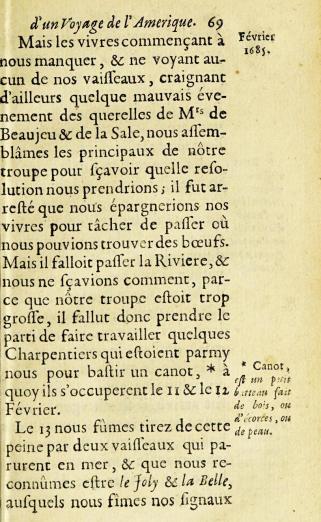

Henri Joutel, "Journal historique du dernier voyage que feu M. de La Sale [sic] fit dans le Golfe de Mexique, pour trouver l'embouchure, & le cours de la Rivière de Missicipi, nommée à present la Rivière de Saint-Loüis, qui traverse la Louisiane...," 1713

Joutel’s text tells the story of the last journey of La Salle down the Mississippi, and of the “tragic story” of his death following a mutiny, using the language of early modern religious fiction. Joutel’s story has a very definite agenda in showing La Salle as “the Hero of this account,” but his work is also filled with engaging details of natural history and ethnographic observation. Joutel was particularly keen to explain new technical vocabulary to his French readers, and here he details the new term canot, canoe, in the margins of his text: “a little boat made of wood, of bark, or of skin.” Elsewhere he takes pains to explain the concept of portage, a process mysterious to Europeans for its confusion of the distinction between land and water.

Joseph-François Lafitau, "Moeurs des sauvages ameriquain. Comparées aux moeurs des premiers temps," [1724]

The Jesuit Joseph-François Lafitau’s extraordinary book on the customs of the American Indians imagines history proceeding in developmental stages; for Lafitau, the American cultures he observed in his time in the Saint Lawrence valley were akin to that of the European ancients, and their cultures could be considered together without regard for history or geography. Lafitau’s comparative method places American canoes alongside the vessels used in Europe before the “high perfection” of more recent shipbuilding techniques. The improbable mash-up of this image shows both Abenaki and Outaouac boats and a place of portage. Lafitau might have seen Americans as “behind” the Europeans, but a sneaking admiration creeps in as he describes the movements of their canoes on water. For Lafitau the bark canoe, that “fragile machine,” was “the artistic masterpiece” of the sauvages.

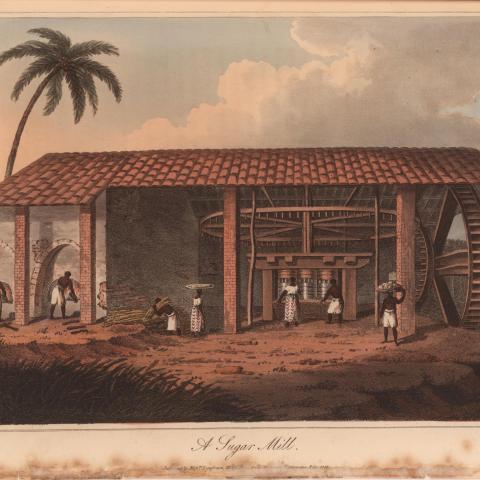

Thinking through aquatic activity

From the sustenance provided by cod fished off the shores of Newfoundland, to the devastation wrought by seas during catastrophic weather events, such as the hurricane and tsunami that devastated Port Royal Jamaica in 1692, to the rivers running through the Americas that taught observers of maps and readers of chronicles about the world beyond their familiar borders, water created, destroyed, and explained the world. Atlases, tracts and treatises document water’s continued utility, both for early modern thinkers as they made sense of the metaphorical nature of humankind and for the people whose work involved traversing a new world.

Juan Huarte, "Examen de ingenios...," 1616

First printed in London in 1594, this treatise on geography and human nature reveals how prominent a role bodies of water were to thinking about human nature in the early modern period. The treatise highlights the enduring importance of Galenic thought to thinking about the “nature” of different people and places, revealing the centrality of “the waters which they drink” to people’s perceived character and how they ought to interact with one another and with the world. It was this “drinking of divers waters” that contributed to the diversity of populations around the globe.

Peter Heylyn, "Mikrókosmos. A little description of the great world," 1625

Written in 1625 as news of the global encounters flowed into London, this “little description of the great world” offered a way to make manageable the complexity of a world whose borders and composition were rapidly shifting. Water bodies – rivers as well as seas – in this compact account of global variety were not dangerous routes into unknown territories, but rather portrayed as the rich veins through which the earth’s sustaining lifeblood flowed. Rendering seas and oceans as metaphorical channels rather than actual channels, Mikrókosmos normalizes the notion of waterborne connection and commerce as being central to the health of the global body and the circulation of people and goods. Understanding the nature of rivers and seas made them less threatening and instead reduced them to a natural body that could be mastered and made to serve the needs of humankind.

"A Full Account of the Late Dreadful Earthquake at Port Royal in Jamaica...," 1692

Water where it shouldn’t be—in the swampy wetland described above, or inundating a city, as described in this account of the 1692 earthquake that laid waste to the leading town of seventeenth century Jamaica—caused complex problems: not only death and destruction but the undoing of civil society. Port Royal, like every Caribbean town, depended upon the surrounding seas for its character and its livelihood—both the longstanding piracy business and the growing plantation economy and its enslaved labor force—but the destruction wrought by the hurricane drove this point home as the town sought to assess and recover from the damage unleashed by the element that normally enabled its prosperity. In this account of the “terrible earthquake,” the sea makes itself felt once again as the protagonist of the drama: the source of devastation but also survival. The author of the account narrates how “some merchants” persuade him to take refuge on a ship in the harbor. He then surveys the destruction from a variety of maritime vantage points: a “canoe”, a “long-Boat”, and simply “from ship to ship” as he ministers to the wounded. Land was the site of death and iniquity—looting, drinking, and whoredom—while all good came by boat from the sea. The author noted that on board a ship, afloat, even the aftershocks were less terrifying. In a “country broken all to pieces”, the sea destroyed but also offered salvation.

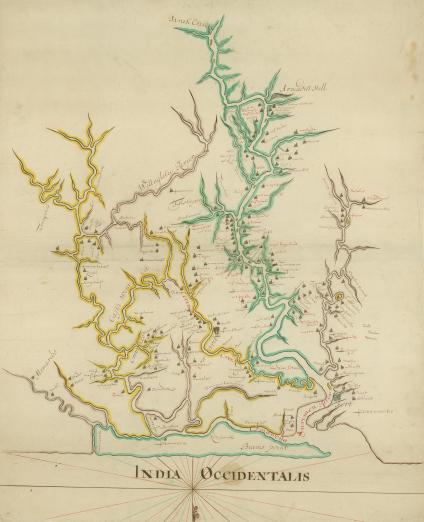

William Blathwayt, [The Blathwayt Atlas], [1629-1683]

The Blathwayt Atlas is a composite atlas, consisting of 48 manuscript maps created between 1629-1683, used by the office of Lords for the Committee for Trade and Plantations. The atlas is an extraordinary compendium of imperial knowledge and record-keeping and a testament to the many different kinds of information and activities associated with rivers. Not only were they places of commerce and maritime travel—and necessitated precise information about depths and coastlines, indicated here on the panel of Surinam by the bathymetric measurements of rivers’ depth—but also information about what happened at particular bends, such as indicated here in the notations “good trading here for bread and drinck”—and “good fishing”.

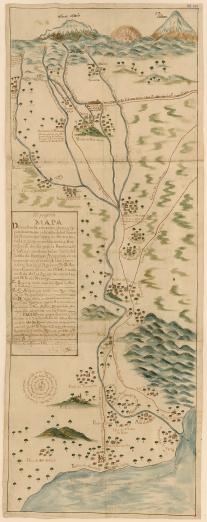

Felipe Zúñiga y Ontiveros, "El presente Mapa Demuestra la cituacion, plano, y repartimiento, que en la actualidad tienen los Arroyos que bajan de Sierra Nevada, y giran entre Poniente, y Sur respecto de ella para la Provincia de Chalco," 1770

This map is the work of Felipe de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, mathematician, astronomer, and scientist, who in 1754 was appointed Royal Land-Surveyor and Hydraulic and Mining Engineer of New Spain. It is part of a legal dispute over water, but more than that it shows all of the works of irrigation and water management in the area of Chalco, to the south of Mexico City. All of the haciendas and pueblos de indios (indigenous towns) were in the path of the water coming down from the Sierra Nevada in the north. Competition for water and land among privately owned haciendas and the communal lands of the indigenous towns increased over time. The water in the south is Lake Chalco.

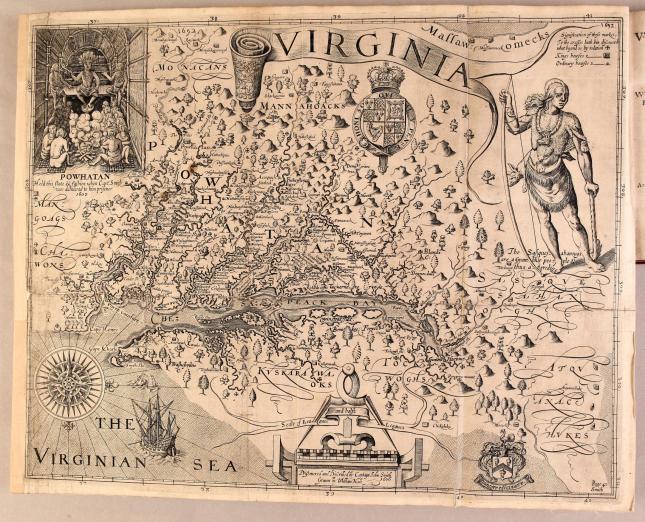

John Smith, "A map of Virginia...," 1612

This classic early description of Virginia is perhaps best known for its intricate depiction of the geography of the Chesapeake bay and its tributaries and inhabitants. Among the maps’ many features, the York and the James Rivers are described not only in terms of their navigable depths (and the types of boats that can ply these waters) but also the peoples living along them and their war-making capacity. The James River is particularly densely annotated, and the observations make clear that it is a river not just for navigation but for making homes and finding sustenance. The little bay at point Q has remarkable “bays and creeks” that “make that place very pleasant to inhabit” and tributaries so rich that “we lived 10 weeks upon oisters.” Rivers and bodies of waters on many maps did more than just provide navigational aids: they provided their own microcosm of reflections the nature of the people, lives, and work to be lived alongside them. Along with the selection from the Blathwayt atlas, also included in this exhibit, the map includes careful labeling of the types of business and work that are conducted along its shores. Rivers, in this portrayal, are more than just navigable bodies of water; they are also the meeting point of people and the sites of trade and business.

"A Commission for the well governing of Our people, inhabiting in New-foundland, Or traffiquing in Bayes, Creekes, or fresh Rivers there," 1633

This early seventeenth-century tract reveals that governance of New Foundland, one of the earliest and, due to its cod fishery, one of the most central settlements of the Americas, was a matter of policing the behaviour of subjects on land and at sea. In order to prevent the “inconveniences” brought about by quarreling subjects, the [tract] aimed to address “in what manner our people in New Foundland and upon the Sea adioyning, and the Bayes, Creekes, or fresh Rivers there, shall be guided and governed…”. The [tract] also addresses improper waste disposal in the harbors, ordering that “anything” hurtful to the Harboures..be carried a shoare, and laid where it may not doe annoyance.” In further reflection on the way in which the labor of the cod fisheries shaped the social relations on land at see, [it was ordered] that “no person whatsoever, either Fisherman or Inhabitants” do any damage to the fisheries’ apparati. Several laws in this 11-page booklet highlight the various social covenants that seaborne labor forced reflection upon.

Tomé Cano, "Arte para fabricar, fortificar, y aparejar naos de Guerra, y merchante...," 1611

Written by Tomé Cano around 1608, this treatise (the first monograph on shipbuilding in Spain) on constructing and equipping warships is stylized as a dialogue among three friends who review the various types of labor that go into the construction of vessels. Over the course of the men’s conversation as they sail down the Guadalquivir river near Seville to the wharves where the boats are built, they reveal the world of work that went into maritime exchange, from the construction of the ships themselves, to the mastery of the intricacies of sailing and the routes and rhythms of particular bodies of water, to the far-flung networks of labor and expertise that kept this world afloat. This treatise pulls back the curtain on the mythical world of waterborne exploration, revealing the infrastructure of labor and mastery that went into boatbuilding.

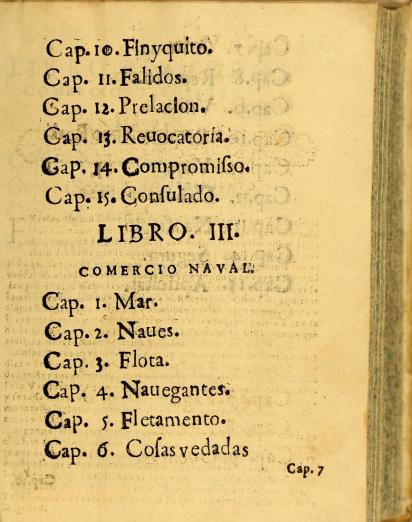

Juan de Hevia Bolaños, "Labyrintho de Comercio Terrestre y Naval Donde Breve y Compendiosamente se trata de la Mercancia y Contratacion de tierra y mar… ," 1617

Written in the rich South American colonial city of Lima, the “Labyrinth of Terrestrial and Naval Commerce” offers another intricate glimpse of the world of work associated with naval commerce. In the third book of this famous treatise by the Spanish-born jurist, he discusses in minute detail the component parts of maritime trade. From a section on the ocean (mar), to the ships (naves), fleets (flotas), customs (aduana), damages (daños), shipwreck (naufragio), insurance (seguro) and more, Hevia Bolaños offers a glimpse of the ways in which maritime commerce drew in people and sectors of society far from the rivers and seas along which boats sailed. Indeed, the pairing of “terrestrial” and “naval” commerce in the work’s title itself points to the contemporary understanding of these two worlds as linked.

A Proclamation Discharging the Transporting of persons to the Plantaions of Forraigners in America, 1698

The sea brought not only natural destruction, it also introduced new dangers to civil society. Boat owners and ship owners plaid a critical role in regulating what was deemed to be the proper flow of people out of, over, and beyond the seas. In this proclamation prohibiting both “Natives” and “Forraigners” from arranging to have people transported from “Our Ancient Kingdom” to “Plantations belonging to Forraigners not Natives of this Kingdom, without leave and allow first obtained from our Privy Council.” “Master or owners of Ships” are singled out as needing to take special care not to engage in this practice. Even as unprecedented riches and beguiling tales of new world explorations circulated throughout Europe, these glimpses of dismay at a perceived tide of migrants into unfamiliar lands underscores the prevailing recognition that the sea—and the world of maritime commerce it enabled—could take as well as provide.

Case of Some of the Adventurers and Participants with the Right Honorouble William Early of Bedford in the Draining of the Great level of the Fens stated, in reference to a Bill depending in Parliament for settlement of the said Draining, 1664

In addition to reflections on the nature of water and the types of work and societies that developed at sea and along its shores, particular bodies of water—or land in need of water-- also generated complex projects and labors. The mid-seventeenth-century English project of transforming eastern English wetlands (known as the fens) into arable farmland raised issues of landownership and usage as well as hierarchies of class and perceptions of civility. In this short document—embedded in a book containing references to other signature projects of the English domestic and overseas ambitions in the seventeenth century, such as the transatlantic slave trade and the royal African company—the gentlemen involved in this project negotiate the terms of their agreement.

Controlling the waters of Tenochtitlan

Perhaps no urban center in the Americas rivals Mexico-Tenochtitlan – the city-state of the Mexicas conquered by the Spanish in 1521 – in its founders’ and inhabitants’ master manipulation of the city’s waters and surrounding lands. In 1325, Mexico-Tenochtitlan was founded on a small island located in the lowest point of a basin surrounded by mountains. More than 50 rivers flowed into the basin, joining their waters with those of the five interconnected lakes in the area. The island’s location, along with the heavy rains of the summer months and the population’s dependence on agriculture, made it natural for people to construct their way of life around water, which was an essential component of the Mexicas’ political, economic, religious, and everyday life. In the Mexicas’ understanding of the world, water connected everything – human beings to gods, environment to politics, technology to ethics, and sustenance to violence – in ways that are only now beginning to be understood.

In particular, the maps of Mexico-Tenochtitlan displayed here were made in order to understand and control water and land in the area. According to Hernán Cortés’s letters to Charles V recounting the war of conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the water of the surrounding lakes and the complex hydraulic system created by the Aztecs and their subjects determined the fate of the conquest, achieved in 1521 after two months of daily fighting. According to Cortés, the side that was able to control the water would win the war, and every day at least 10,000 indigenous allies dedicated themselves to destroying the Aztecs’ canals, while the latter repaired them at night. After the conquest, the importance of water shifted to agriculture in terms of economic production, and to urban planning, since flooding became the most prevalent problem in the colonial city, which suffered many floods, the worst one starting in 1629 and lasting for five years.

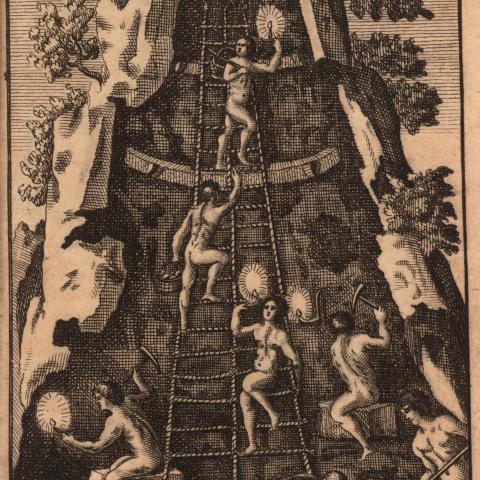

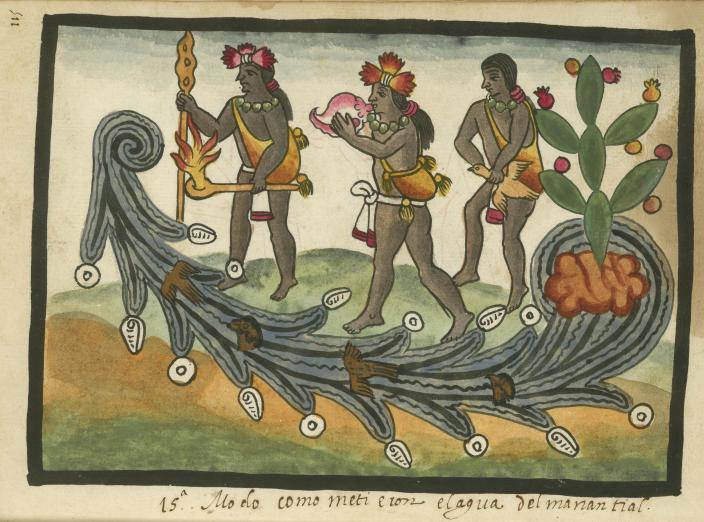

Juan de Tovar, [Tovar Codex], [s.n., between 1582 and 1587]

Ahuitzotl, tlatoani (king, “He Who Speaks”) of Tenochtitlan (1486-1502), directed Tzotzoma, the ruler from Coyoacán, to deliver the waters from the Acuecuexo stream to Tenochtitlan, but Tzotzoma, knowing the turbulent nature of these waters, warned against the idea, enraging Ahuizotl, who took the advice as a challenge to his rule. Ahuizotl ordered Tzotzoma killed, but like other people identified as knowledgeable about water, the latter was considered a great sorcerer and managed to escape several times by transforming himself into something else – an eagle, fire, water. In the end, Tzotzoma gave in in order to save his people. This image, from the chronicle written by Juan de Tovar, a Jesuit priest in 16th century Mexico, shows three priests (identified by their ritually blackened bodies) who perform ceremonies and sacrifices (of children—common in water rituals—and birds). The priests are inviting the waters from Acuecuexo (addressed as Chalchitlicue) to come to Mexico-Tenochtitlan. As Tzotzoma had warned, the waters soon flooded Mexico-Tenochtitlan and had to be sent back to their original place in Coyoacán.

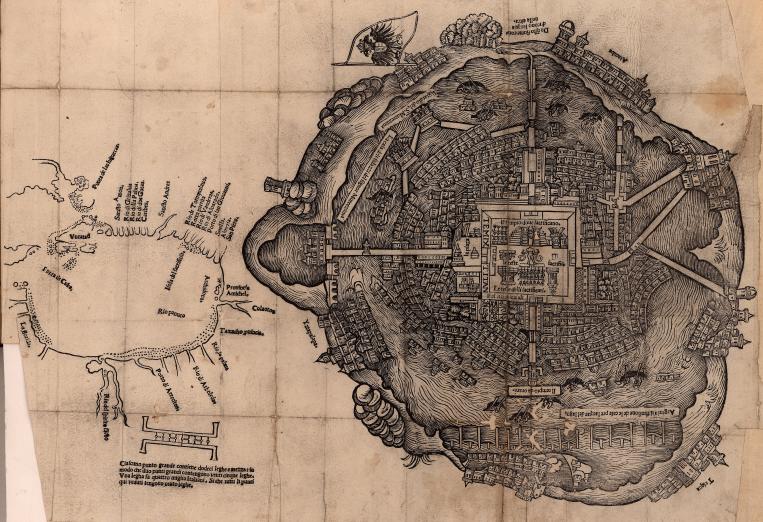

[Map of Temixtitan and map of the Gulf of Mexico] in Hernán Cortés, "Praeclara Ferdina[n]di…," 1524

This map, sent by Cortés along with his letters to Charles V and published in Nuremberg in 1524, is the first pictographic representation of the city seen in Europe. The north is on the right. Visible in the east (the bottom of the image) is part of an indigenous dike created to prevent flooding during pre-Hispanic times, but it also served to separate fresh water from salty water. The former came from rivers and lakes in the South (Chalco and Xochimilco), while the brackish water came from Texcoco, the main lake. Because of the indigenous representational style of the dike, art historians believe the map Cortés sent is a copy of an indigenous one. Nevertheless, many other elements such as the houses and the main square are decidedly non-indigenous. The extensive manipulation of the area (dikes, canals, bridges, and streets built on the water) is clear, as is perhaps the beauty of the city in the eyes of the Spanish, who soon after seeing it and describing it for the first time for a European audience, razed it.

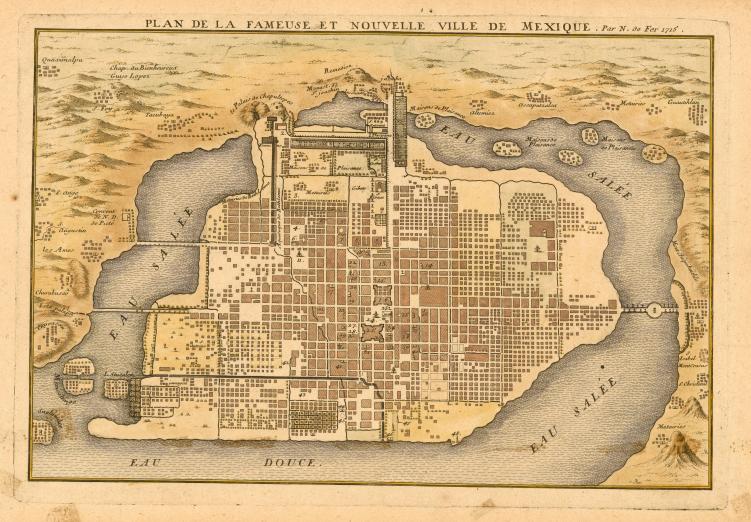

Nicolas de Fer, "Plan de la fameuse et nouvelle ville de Mexique…," 1715

This map of Mexico City includes a schematic representation of Lake Texcoco and its divisions. The city is still surrounded completely by water in spite of the more than one century of drainage works initiated in 1607. This map was accompanied by a separate sheet describing it and including a lettered key of important locations.

Notice the contrast between the city delineated so well and the unrealistic location and form of the lakes. The structures of the aqueducts coming from Chapultepec are visible in the north (the west in the real city). Some remnants of the aqueduct still exist in Mexico City today.

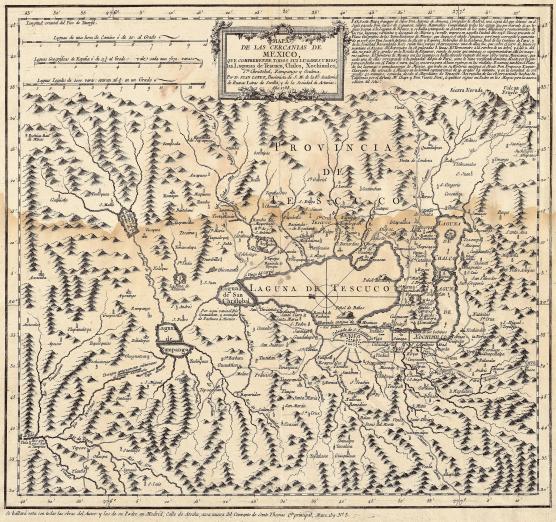

Juan López, "Mapa de las Cercanias de Mexico que comprehende todos sus lugares y rios…," 1785

This is a map derived from the Mapa de Sigüenza y Góngora Sigüenza map, a map originally made by polymath Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora in 1692 when the city suffered from severe flooding. It shows with more clarity the location of the city in relation to the mountains and the enormous lake. When compared to it, and especially if one takes into account the many rivers carefully represented, Mexico City appears small, vulnerable. The map, laid out in a West-East direction, also gives us another view of the enormous importance of the Sierra Nevada (upper-right corner) very prominent in the Chalco map of 1754.

As we can also see here, everything (lakes, rivers, mountain ranges) was interconnected. Notice as well the extensive hydraulic works, and especially around Lake Zumpango, in the middle left, the drainage system built to rid the city and its environs of excess water. As the map shows, drained water was directed to Río Tula (left bottom corner) and from there to Tampico.

Joseph Francisco de Cuevas Aguirre y Espinosa, "Extracto de los autos de diligencias, y reconocimientos de los rios, lagunas, vertientes, y desagues de la capital Mexico, y su valle…," 1748

Finally, since control of water was and remains so important for the region, it is not surprising that considerable effort has been dedicated to knowledge production, expertise, and know-how about water, even today. From priests (some of them meteorologists, no doubt), laborers, divers, and agricultural specialists in Tenochtitlan, to engineers (many of them priests as in pre-Hispanic times), indigenous workers, and experts on hydrology in colonial and independent Mexico City, knowledge about water was absolutely necessary to make life there possible.

Therefore, it is also not surprising that compilations of texts documenting previous problems (such as floods and mechanisms to control them) have been created periodically in order to have a full historical and technological account of what plans have been carried out, which ones have not, and why. Here we find a manuscript from the colonial period. It is striking that water created even the need for these kinds of compilations, this one a small archive in its own right that indirectly demonstrates the intertwining of government practices and technology, the management of the environment and of knowledge production.

Related Events

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

Credits

This exhibition was curated by Ivonne del Valle (University of California, Berkeley), Katherine Ibbett (Trinity College, University of Oxford), and Molly Warsh (University of Pittsburgh).