The Americas on Fire

Of all terrestrial species, only humans ever learned to control fire. They domesticated it to warm their homes, ignited it to turn plants and animals into food, stoked it to transform wood into power, and channeled it to refine ore into currency. Manipulated by human hands, fire became a weapon of war and a conduit for communicating with the gods. Europeans and Native Americans also used fire for unspeakable cruelty during the period of conquest as they fed one another to the flames in the name of their gods. And yet for all the ways that humans used fire to their own ends, it proved a rebellious servant that frequently eluded control by its putative masters.

The collections of the John Carter Brown Library record the inextricable link between fire and all facets of the American experience. The Americas on Fire, guest curated by historians Jake Frederick (Lawrence University, USA) and Júnia Furtado (Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil), depicts fire harnessed for agriculture, embraced as a mechanism for communicating with the divine realm, and wielded in combat by Native Americans and European colonizers alike. The exhibition sheds light on how the human experience of the Americas has – for better and for worse – always been shaped by fire.

The Fires of Daily Life

When Europeans wrote about the culture of the Americas, they included within their descriptions many familiar ways that fire pervaded the daily life of native peoples. Fire heated the home and provided flame for cooking. Fire was used to shape wood for practical purposes, such as building canoes or preparing land for cultivation. Fire also served to sanctify religious ceremonies and to facilitate worship. Fire was an instrument of culture, and its many uses had to be handed down with care from generation to generation.

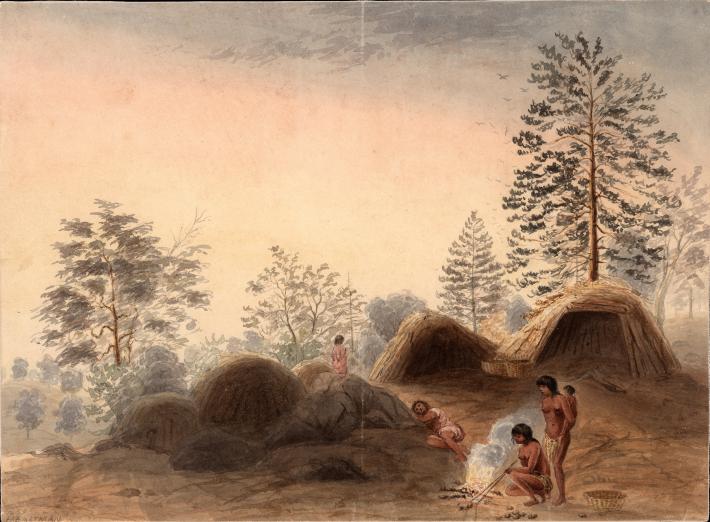

Harrison Eastman, [Indians around a camp fire], 1852

The fire pit often served as the symbolic center of Native communities. It provided warmth, enabled women to cook meals, and allowed much of the social and ceremonial life of indigenous American societies to unfold in its glow. This image shows an indigenous family in the American southwest in their daily activities around the fire.

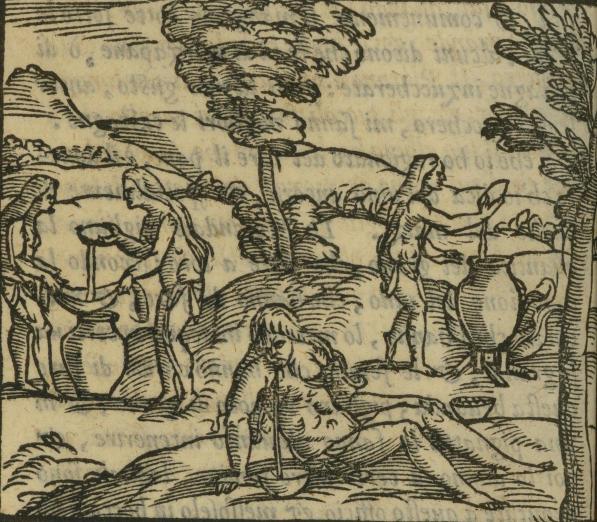

Modo di fare il uino, 1565

This early image shows Native women on the island of Hispaniola in the several stages of preparing and cooking an alcoholic drink made from fermented corn. One woman chews and spits out the mashed corn, activating fermentation. The mash is later strained, and in this instance, heated in a jar over fire.

This process, by which saliva was used to activate the fermentation of some starch, was not uncommon on both sides of the Atlantic. Natives of Brazil made Cauim from manioc in the same fashion.

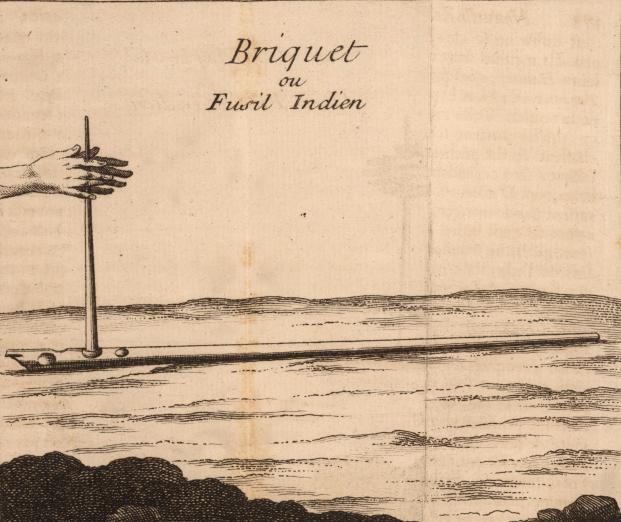

Mathey, engraver, Briquet ou Fusil Indien, 1743

Between 1723 and 1725, French botanist Pierre Barrère surveyed plants on the island of Cayenne (off the coast of French Guiana) with a particular eye toward their economic and medicinal potential. Barrère was unimpressed with Native medical practices, claiming that all they knew they had learned from Europeans. He did, however, record other ethnographic information, including how Natives of the island made fire.

In this image, the technology for lighting fires is graphically divorced from the people who used it. Barrère's interest in the Native fire-builder only extends as far as his hands, enabling the viewer to see how the implement is used but, characteristically, removing the individual’s identity from this indigenous technology.

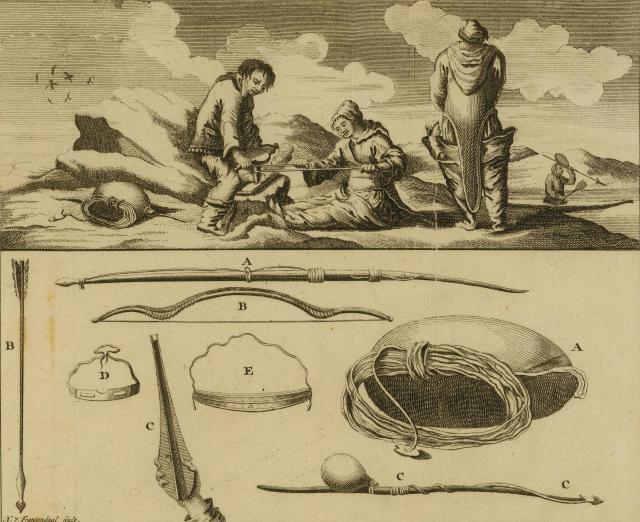

Nicolaes van Frankendaal, engraver, Exkimaux, faisant du Feu, & tirant au Vaux-Marins. Exkimaux, vuur maakende & naar Zee-Kalven schietende, 1750

An understanding of fire was essential for human survival, and also for the propagation of culture. Fire allowed Native peoples in northern climes to protect themselves from cold, but also permitted the creation of cooking traditions and even communication. This image shows a group of Inuits making fire, and includes several additional artifacts.

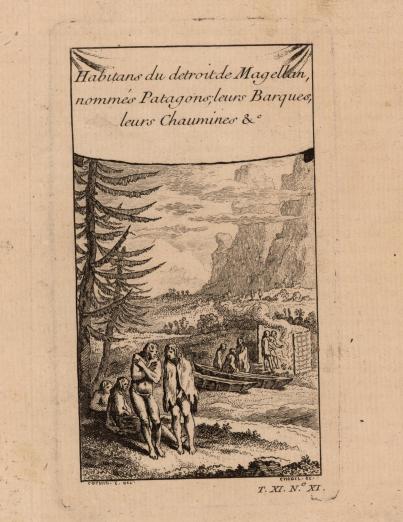

Cochin E., designer, and Pierre Quentin Chedel, engraver, Habitans du detroit de Magellan, nommés Patagons; leurs Barques, leurs Chaumines, 1746

Francis Froger was an adventurous Frenchman who participated in a voyage to the Americas between 1695 and 1697, setting sail when he was just 19 years old. The expedition reached as far as the Straights of Magellan, where contrary winds prevented their six ships from reaching the Pacific Ocean. While in the farthest reaches of South America, Froger recorded his observations of the Native populations.

In this image, we see Patagonians attempting to fight off the cold by building a fire and enclosing it within a three-sided shelter, as a way of protecting the fire from the wind and directing the heat toward themselves. Fire could transform even the most extreme environments, including Patagonia, into places of refuge.

[Native Americans make canoes by building a fire inside the canoe], 1707

Four fires appear in this image of canoe building in Virginia. Two Native Americans in the center of the image use fire to hollow out a log into a canoe; one fans the flames while the other scrapes away the burned wood. Two other Natives attend fires by a felled tree, while a fourth fire burns at the base of a standing tree.

The steps of canoe building are combined in a representation reminiscent of an assembly line, showing how fire could be harnessed for constructive ends.

[Hunting Scene], 1631

In this scene, Native Americans in what would become New England use fire as a tool for hunting. Bonfires drive game into a river, where they are more easily slain by hunters. Indigenous peoples in many parts of the Americas used fire in this way, occasionally employing fire to improve hunting grounds by intentionally setting fire to the forest understory.

Once fires burned through the grasses and brush, new growth would attract deer and other herbivores that browsed on tender shoots. Such fires also opened up sightlines making game easier to spot.

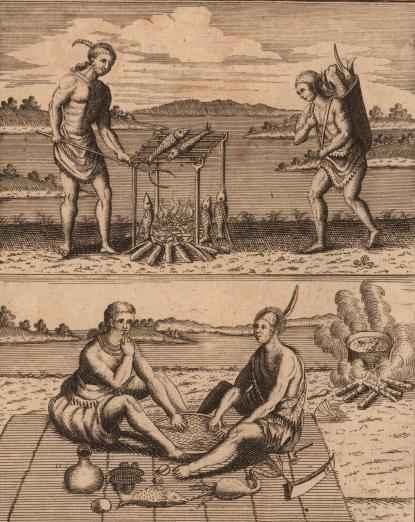

Wie sie ire Fisch Wildpret und andern järlichen..., 1591

Alligators, snakes, fish, and small deer are shown in great detail being grilled over a fire. One can almost smell the aromas as one man fans the flames and another brings more game to the already crowded grill.

[Haushaltung der Virginier], 1777

In Johann Georg Purmann's 1777 depiction of Virginian Natives, men come together to cook fish over a fire. In the frame beneath, a man and woman sit together and eat from a common bowl, while a pot of fish stew simmers gently over another fire in the background. Around them are examples of commodities, including fish, maize, and tobacco, each of which is made usable and catalyzed by fire.

Quibus remediis contra morbos, 1619

Just as in early modern European medical practice, fire and smoke were important tools against disease in the Americas, and they were employed both ceremonially and as medicine by indigenous peoples. Here, Natives of Paria use fire in order to avoid the spread of plague among the tribe.

Brazilian Indians used smoke to cure a very common disease of the time named Maculo or Doença do Bicho, an intestinal inflammation that was frequently fatal. Portuguese doctors learned to treat this disease from Native medical practitioners.

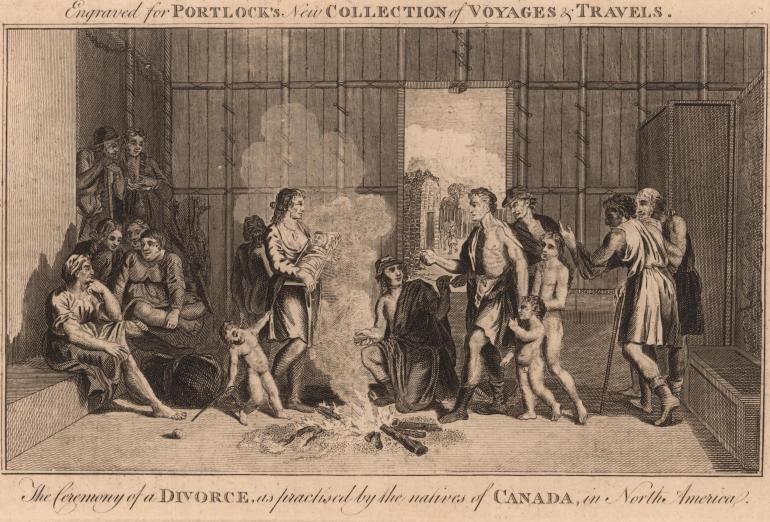

The Ceremony of a Divorce, as practised by the natives of Canada, in North America, 1794

Fire was significant in various social, cultural, and ceremonial practices of indigenous groups throughout the Americas.

This divorce ceremony, performed by the Natives of Canada, takes place in a cabin around a fire, where the smallest member of the couple’s progeny is bathed in the swirling smoke.

[Fig. 132. Burial practices of the natives of Venezuela], 1819

The Yanomami of the Amazon Basin had their first contact with Europeans through a Spanish expedition in 1759. As late as the early nineteenth century and beyond, their culture remained a focus of exotic fascination for Europeans.

In this depiction, their burial rituals include the incineration of the deceased, whose ashes would then be consumed by survivors as a means of preserving a connection with the dead. Fire frequently played this kind of ceremonial role in funerals across the Americas.

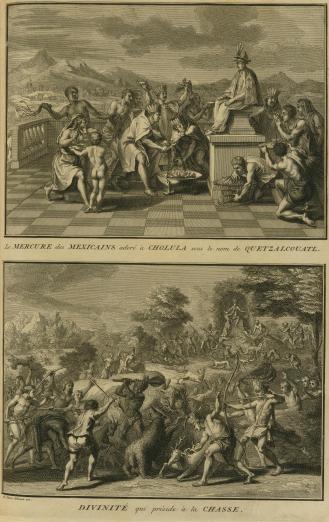

Le Mercure des Mexicains adoré à Cholula sous l..., (1723)

Prior to European colonization, fire – or its celestial incarnation, the sun – was praised by many Native groups, including the Incas and Mexicas.

In this elaborately illustrated French book, the upper image demonstrates various blood offerings to the statue of the Mexican deity Quetzalcoatl. Men are seen piercing their tongues and ears and collecting blood as a tribute to their god. In front of the idol, two priests sacrifice the blood of a bird by pouring it into a fire at the base of the statue.

In the bottom image, another idol from central Mexico presides over a hunt, while fire is once again present in the form of a torch, grasped by one of the many participants.

i 1a figura Uitzilopuchtli, idolo principal de los Mexicanos, 1582

The adoration of fire embodied in the cult of the sun appeared in many indigenous cultures. This image depicts the Mexica god Huitzilopochtli, the god of sun and war, whose association with the power of fire is inherent in the image of the god itself and would have been easily recognizable by devotees of Huitzilopochtli.

The turquoise snake in Huitzilopochtli's right hand is a mystical weapon, the fire serpent, whose orange tongue evokes a flaming rod.

Contact, Confrontation, and Condemnation

As Europeans crossed the Atlantic and attempted to subjugate Native inhabitants, fire served as an instrument of coercion and a measure of and justification for depravity. Ritual cannibalism among the Native peoples of the Americas shocked European observers, who grossly exaggerated the frequency of this practice in accounts presented to Old World readers. Such “savage” behavior helped Spanish conquistadors justify the violent conversion of Native communities.

In response, indigenous populations also put Europeans to the torch, burning them in revenge for mistreatment. The viciousness of the conquistadors would later be used by other European powers as evidence of a characteristically Spanish brutality. In many of the following images, Spanish conquerors are depicted in much the same manner that early Portuguese and Spanish images represented indigenous Americans: as barbaric killers.

[Montezuma's Dream], 1707

This image reveals fire destroying the Aztec capital city, an omen supposedly experienced by Moctezuma prior to the arrival of Cortés.

Following the conquest of Tenochtitlán, Native informants told Spanish chroniclers that Moctezuma had foreseen omens of the fall of his empire. Though almost certainly invented after the fact to explain the failure of Moctezuma to adequately respond to the Spanish assault, the story of preordained defeat was embraced by the Spanish.

The notion that the defeat of Tenochtitlán was fated to occur aligned well with Spanish notions of a righteous destiny to possess the Americas.

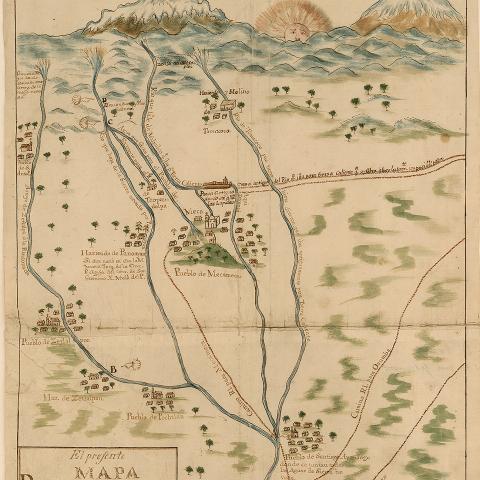

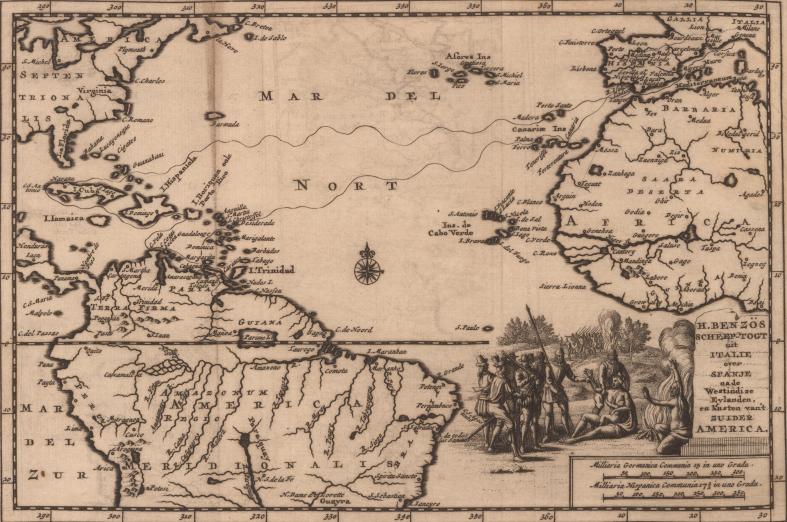

H. Benzös scheep-togt uit Italie over Spanje na..., 1707

In the 1540s and 50s, Italian adventurer Girolamo Benzoni travelled through the Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and adjacent mainland of Central and South America. During his voyage, as illustrated on this map, Benzoni developed a hatred of Spain. The account of his travels in Spanish territory did much to advance the Black Legend of Spanish cruelty in the Americas.

In keeping with the anti-Spanish text of Benzoni's account, the mapmaker made sure to include a depiction of Spanish mistreatment of Native peoples. In the lower right hand corner, we see Spanish soldiers accosting two natives sitting around a campfire.

In the background, a group of armed Natives charges away from another fire, perhaps to come to the aid of their comrades, or possibly as allies of the Spanish soldiers.

[Burial ceremony of a chief], 1707

This fanciful image of the burial ceremony of a Native chief appears to have been inspired by the travels of Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, an early Spanish explorer who witnessed the death ceremony of a Native ally in Panama.

The buildings in the background seem to draw on European or even classical imagery, likely bearing no resemblance to the structures Balboa would have seen among the Natives of the region in 1513.

The fire in this image serves as a means to commit an important leader to the spiritual world, a notion as likely drawn from preconceptions of the artist as from Balboa's own experience since fire was often seen the world over as a conduit to the spiritual realm.

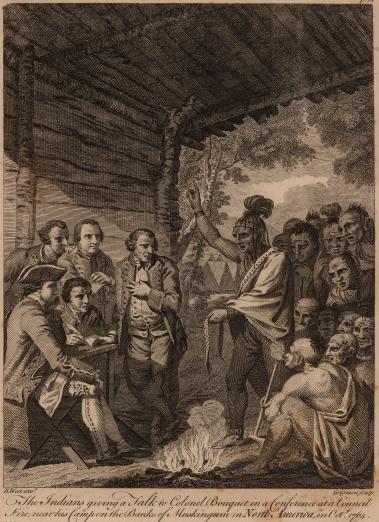

The Indians giving a Talk to Colonel Bouquet in a Conference at a Council Fire, near his Camp on the Banks of the Muskingum in North America, in Octr. 1761, 1766

Holding a wampum belt with one hand and gesticulating skyward with the other, a Native American leader (possibly a Seneca, Delaware, or Shawnee) addresses a group of Europeans around a council fire.

While the Natives presumably reside in the encampment depicted in the background, the negotiating parties share the wooden shelter and confer around a symbol of domestic peace: the hearth fire.

The juxtaposition of a Native American with a peace pipe and a European recording the proceedings with a quill demonstrates the methods used by each group, respectively, to formalize agreements with the other. Both, however, rely on the fire.

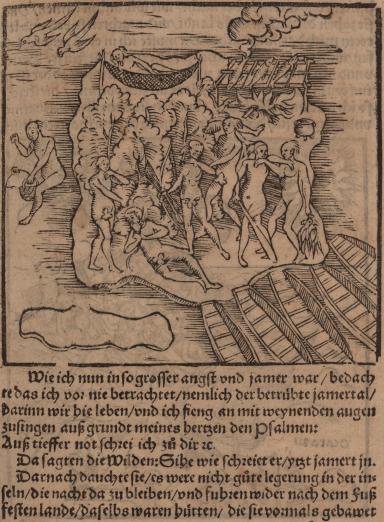

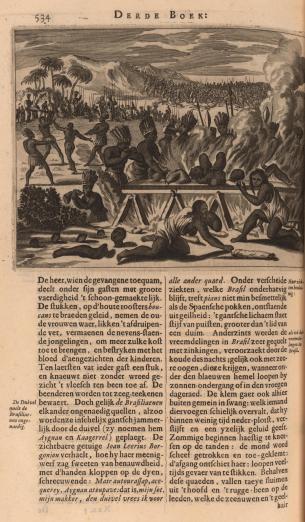

[Was sich auff der wider umb reyse begab nach irem lande], 1577

Hans Staden was a German soldier who travelled to Brazil in the service of the Portuguese. Captured by the Tupinambá, he was held for three years, after which he escaped and wrote a narrative of his captivity. His stories of cannibalism by the Tupinambá have been criticized by some as sensationalist and designed to sell more books.

This image here, of fire domesticated for "savage" activity, may indeed have been attractive to buyers in Germany eager for tales of the exotic peoples of the New World.

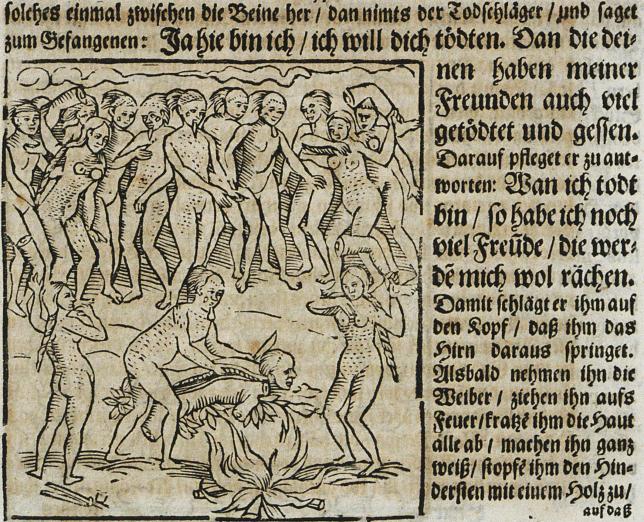

[Ritual killing of captive], 1664

Hans Staden's 1557 book was only the first to publicize the shocking custom of cannibalism among Brazilian Natives. According to Staden, Brazilian Natives used fire to cook their prisoners before eating them, as seen in this image from Winckelmann’s New World travelogue.

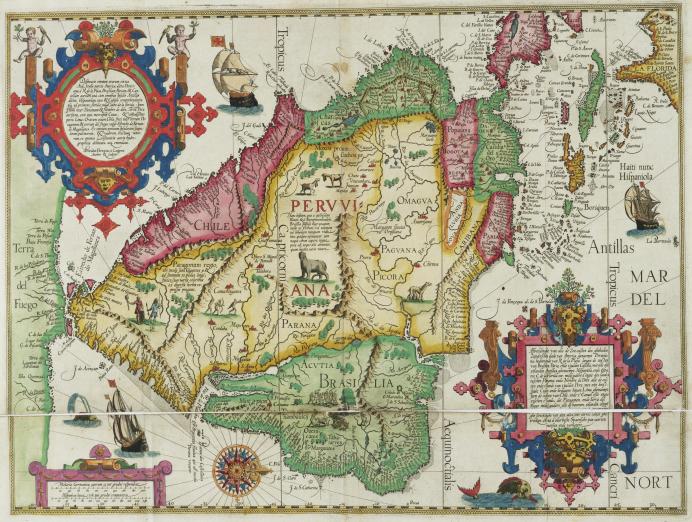

Delineatio omnium orarum totius Australis partis Americae ... Afbeelinghe van alle Zee-custen des gheheelen Zuyderschen deels van America, 1596

After Hans Staden, Brazilian Natives were often represented through scenes of cannibalism, frequently cooking their prisoners on a grill over a fire.

Scenes of cannibalism by Native peoples of the Americas later spread to engravings and maps, as shown in the 1596 map of South America by Linschoten, as well as in the following seventeenth-century engraving.

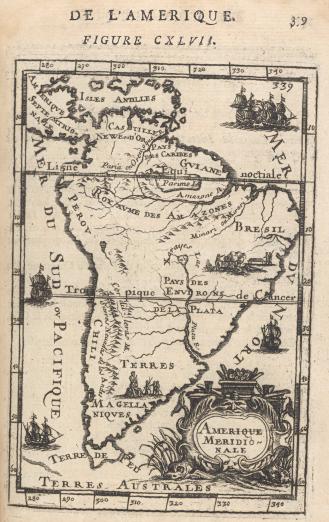

Amerique Meridionale, 1683

[Scene of cannibalism], 1671

This image allegedly represents the warfare of Native Brazilian Tupinambá.

In the background, a great melee unfolds, while to the left three men are about to sacrifice a captive opponent. In the foreground Natives engage in an orgiastic feast.

Amongst the flames of a cooking fire the dismembered corpses of war victims are grilled while victorious Tupinambá Natives gorge themselves on human flesh. European representations of Native peoples frequently substituted sensational images for genuine understanding of cultural practices.

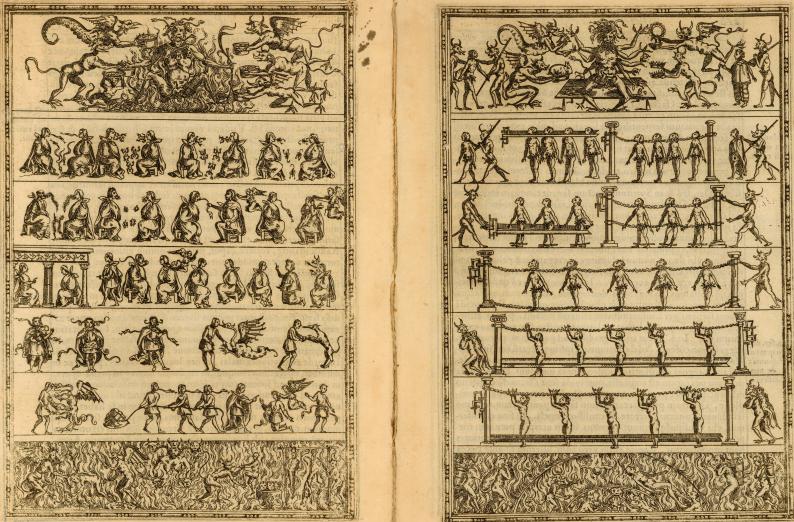

[Idolatrous speech among native Americans], 1579

This series of pictographs demonstrates what might have awaited those who failed to embrace the teachings of Christianity. Fire in this image represents the ultimate threat to Natives who would not accept the will of conquering Spaniards.

In the first instance, demonic beasts come out of the mouths of Natives speaking blasphemies, which appear similar to how "speech scrolls" were depicted in central Mexican pictographic writing.

The right hand series of images demonstrates the consequences of “bad speech”: blasphemers are shackled by demons, awaiting the fate that lies below, while across the bottom of the page the fires of Hell burn sinners and await the arrival of the newly chained blasphemers.

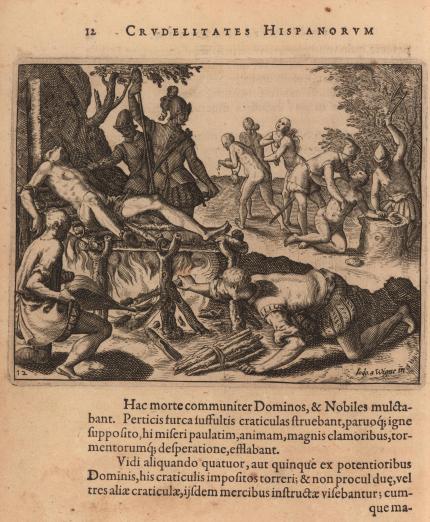

Theodor de Bry, engraver, [Scene of torture], 1598

Fire became an important tool of violence in the confrontations between Europeans and Americans, and was frequently used to enforce European control over Native peoples of the Americas.

The engraver of these images, Theodor de Bry, had been driven into exile after his conversion to Protestantism, and created illustrations that were highly critical of Spanish actions in the New World.

In this scene, Spaniards torture a Native noble by slowly incinerating him over a fire.

Further atrocities in the background reinforce the Black Legend of malevolent Catholic Spaniards abusing Native peoples. Fire here is used to demonstrate the savagery of the supposedly civilized Catholic Spaniards.

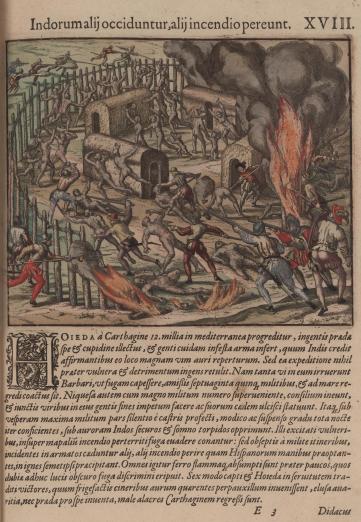

Indorum alij occiduntur, alij incedio pereunt, 1594

In this scene, also produced by the Protestant engraver Theodor de Bry, Spanish soldiers are shown massacring a Native community in Colombia.

This image, published in Frankfurt, is meant to display Spaniards as brutal to the point of barbarity. They have set the village aflame, while soldiers in armor, with lances, swords, and firearms, kill unarmed naked Natives attempting to flee. Pointedly, women and children in the center of the village are clearly fated to be the next victims of Spanish attack, as the soldiers and fire inevitably reach them.

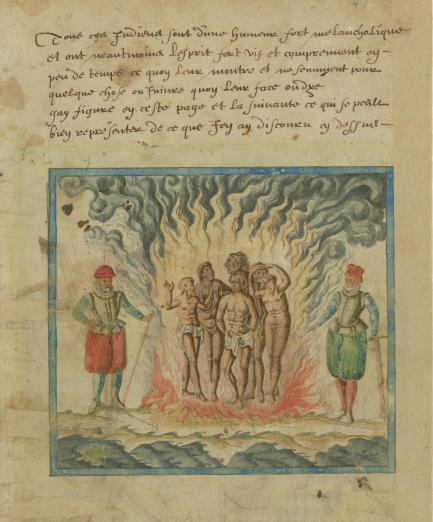

Samuel de Champlain, [Spaniards burn Native Americans], 1602

In yet another European condemnation of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, a pair of Spaniards look on at the burning at the stake of six (likely Carib) Natives.

While the depredations of conquistadors were regularly exaggerated by other European powers to challenge the legitimacy of Spanish claims to the Americas, the level of cruelty actually practiced by the conquistadors is hard to overstate. Native sources also record the prodigious use of fire as a means to torture and execute indigenous peoples of the Americas that resisted conquest or conversion.

Pernambuco, 1624

Fire was used in disputes between European nations as they sought to colonize the Americas. This image shows a view of Pernambuco conquered from the Portuguese by the Dutch in 1630.

One of the war strategies that the Dutch used against the Luso-Brazilians was to set fire to cane plantations, since sugar production was the most important economic activity in the captaincy. The image here shows the phases of sugar production – planting, harvesting, grinding, and cooking – performed by Black slaves.

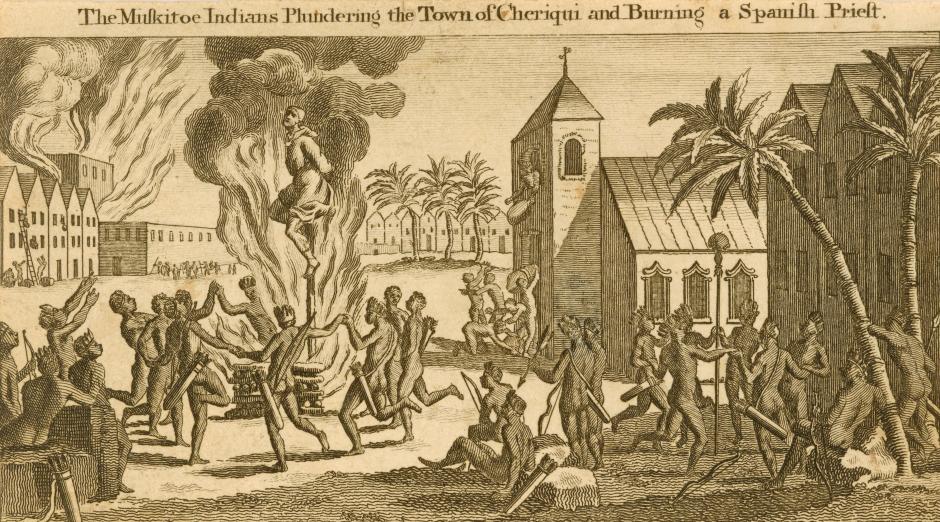

The Muskitoe Indians Plundering the Town of Cheriqui and Burning a Spanish Priest, 1779

John Cockburn was an Englishman who sailed for Jamaica in 1730. Soon captured by Spanish pirates south of Jamaica, he began an epic 2,400-mile journey through the lands of the Caribbean. While lying sick in the Native town of Chiriqui, in Panama, he claimed to have witnessed an attack by the Mosquito Natives.

The Mosquito, seeking vengeance for Spanish mistreatment of Native peoples, captured a Spanish Franciscan who was residing in the town. The priest was then tortured and burned on a pyre. Cockburn was quick to note that the noble reputation of Englishmen among the Natives spared him from being put to the torch himself. Fire in this scene had become a tool for retribution.

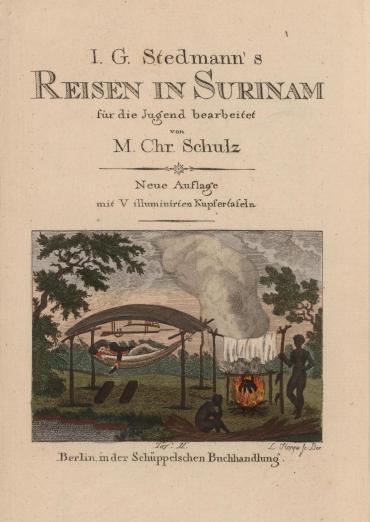

John Gabriel Steadman, I. G. Stedmann’s Reisen in Surinam, Neue Auflage mit V illuminirten Kupfertafeln, 1799

In this 1799 image of a soldier and two slaves in Surinam, fire is twice domesticated. Put to use by the slaves to cook food and dry laundry, the fire is controlled in the service of the soldier, in the same way as the two slaves.

The soldier's contrast to the slaves could not be more striking. As he relaxes in a hammock, one slave is tending the fire while the other appears to sit dejectedly. And while the slaves can manipulate this simple form of fire, hanging above the soldier at the ready is a far more lethal form of fire: a firearm.

Commodities and Consumption

Tobacco and cacao are native to the Americas, and prior to contact, both were unknown in the Old World. These two commodities proved to be among the unforeseen riches of the Americas. Through the application of fire, each fundamentally changed European tastes. Inhaling the burning fumes of tobacco was imagined to cure a variety of ailments, and its sale was quickly proven to make money. Europeans’ obsession with tobacco transformed this American crop into a global commodity. Long esteemed by Mesoamerican cultures, cacao beans were fermented, toasted, and ground into drinks. Both tobacco and cacao were exchanged as currency as well.

The Indians in their Robes in Councel, and Smoaking tobacco after their way, 1699

Lionel Wafer was a Welsh explorer who, in 1679, joined an English privateering outfit. He was later stranded in Panama for a year, only to return to making pirate raids against the Spanish before ultimately retiring to Philadelphia. During his stay in Panama he recorded various practices he observed among the Natives of the region, including this method of consuming tobacco.

In this scene, men are gathered in a hut where a small boy blows tobacco smoke at them. Wafer described the practice, “A Boy lights one end of a Roll and burns it to a Coal, wetting the part next it to keep it from wasting too fast. The end so lighted he puts into his Mouth, and blows the Smoak through the whole Length of the Roll into the Face of every one of the Company or Council..." Before Europeans reshaped the nature of tobacco consumption, it was often consumed ritualistically and in very high doses.

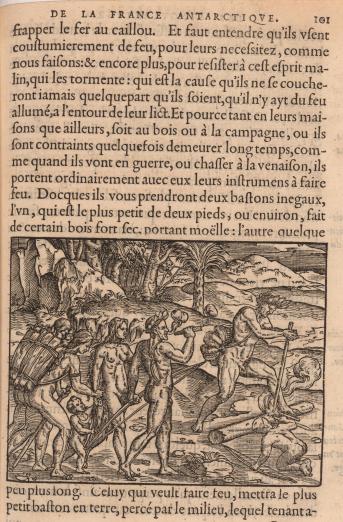

[Methode des Sauuages à faire feu], 1558

The Franciscan priest and cosmographer André Thevet stayed only one year (1555) in Rio de Janeiro during Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon’s expedition to establish a French colony (La France antarctique) in Brazil. In his book Les singularitez de la France Antarctique, published after his return to Europe in 1557-58, Thevet opposed Staden's discourse of Native savagery. For Thevet, the Brazilians’ dominion over fire was an important sign of civilization and he was one of the first to support the idea of the “good nature of uncivilized people” (also known as the myth of the Noble savage).

Thevet was also among the earliest Europeans to bring the tobacco plant to the Old World, where he tried to name the plant Angoumoisine to celebrate his city. The image shows the methods by which the Native peoples of the Americas made fire while an onlooker smokes the tobacco weed.

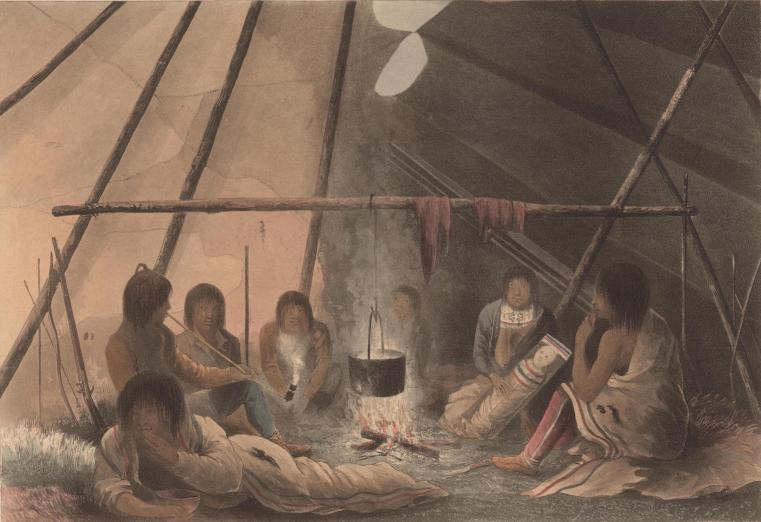

Robert Hood, designer, and Edward Francis Finden, engraver, Interior of a Cree Indian Tent. March 25th. 1820, 1823

This scene documents a moment in the English explorer Sir John Franklin's expedition to map northern Canada. On this first of three voyages to Canada, Franklin rested among a group of Natives, where he ate moose and possibly joined in the smoking we see depicted.

The cooking fire in the center of the lodge renders this place, at the edge of the harsh realities of English exploration, cozy and domestic, and a stark contrast from his later fate.

Franklin would die sometime between September 1846 and April 1848 seeking the Northwest Passage on the ships the Terror and the Erebus, both of which were lost and only discovered (in 2014 and 2016, respectively) sunken beneath the icy waters of northern Nunavut.

[Tobacco], 1974

Smoking tobacco spread quickly to Europe and become a symbol of worldliness. This image of a man smoking in his library recounts a story highlighting the novelty of smoking for early modern Europeans.

An American plant, tobacco was unknown to Europeans prior to contact. Sir Walter Raleigh is popularly credited with bringing tobacco and smoking to Europe. One anecdote claims that when Raleigh was experimenting with smoking tobacco, his servant concluded that the explorer was on fire and promptly doused him with a jug of water.

Europeans were so new to smoking that they lacked even a vocabulary to describe it. When Native peoples were seen applying fire to pipes filled with tobacco and drawing smoke from them, they were said to be "drinking smoke."

[Native Americans process cocoa (sic)], 1671

This image depicts Native peoples of the Americas processing cacao. The key ingredient in chocolate, cacao, was highly prized in central Mexico before the arrival of the Spanish. After European contact, it became a popular drink on the eastern side of the Atlantic, and cacao developed into an export commodity.

Processing required several stages, some of which are depicted in this scene. Fire was an essential part of this process, as the cacao was roasted and then mixed with a hot liquid.

The second figure from the right is completing the process of mixing and frothing the hot liquid cacao into a drink.

Fueling Colonization

Europeans and native peoples of the Americas employed fire in the transformation of the landscape, opening up unimagined new spaces for agriculture. Fire's capacity to domesticate landscapes followed Europeans’ incursions across continents. Home fires and signal fires followed European expansion as they sought to "tame" a landscape to their own ends. Fire played a crucial role in expanding commercial enterprises as well. As Spanish colonizers exploited vast silver mines in the colonies, fire was required to smelt ore into ingots, which were then shipped across the Atlantic. Along with ore, sugar thrived on an unprecedented scale in the New World thanks to fire. Brazil and the Caribbean became global centers of sugar production, whereby fire enabled the processing of cane into usable sugar through heating. Sugar production also, tragically, required an enormous amount of human labor, which in turn fueled the transatlantic slave trade.

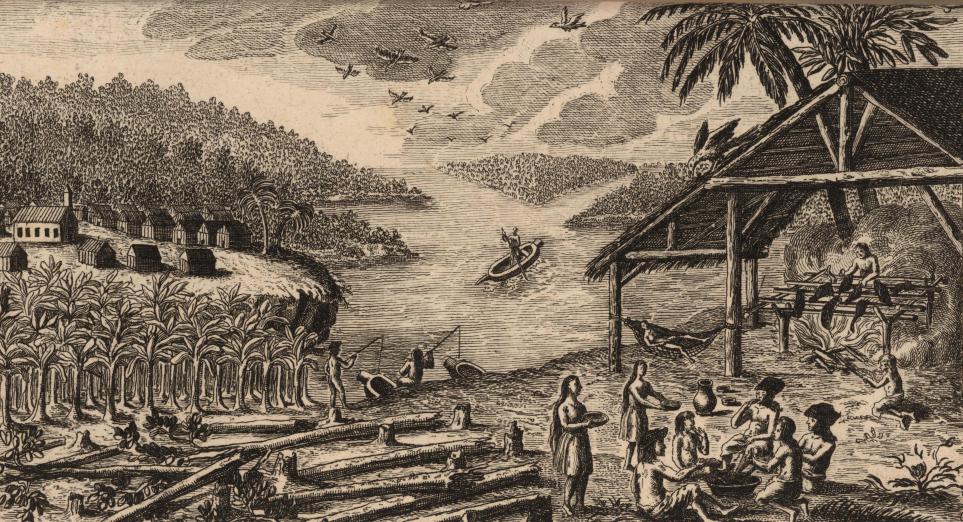

[Amazonian village], 1785

Native peoples of the Americas used fire to clear the land and prepare the soil for agriculture (coivara). This image shows an Amazonian indigenous settlement beside a river.

The nearby forest has been taken down by fire to allow planting of crops, an orchard or palm grove.

Men grill meat over a fire and fish while another lies in a hammock. In the center, women display a welcome ceremony which includes washing the feet of the newly arrived men and offering them food and drink. Swidden, or slash and burn, agriculture was common throughout the Americas.

[Native American goldsmithing], 1707

Silver, gold, iron, and other metals were important natural resources for European trade. In many cases, they used indigenous techniques of metalworking. Europeans imagined legendary hoards of gold over every horizon. This particular image is a fictional vision of Lake Parime, the rumored home of El Dorado located somewhere in northern South America.

Heated in a crucible and poured into a mold, gold was believed to be sacrificed into the lake, waiting to be found by European explorers. Fire in this instance is used to turn gold into artwork, but Spanish and Portuguese colonizers would have been just as happy to see it become ingots or pieces of eight.

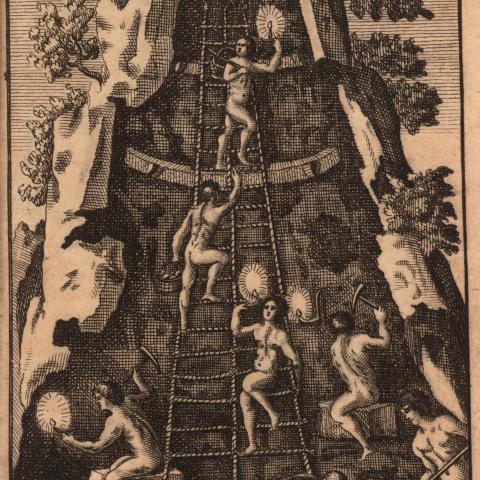

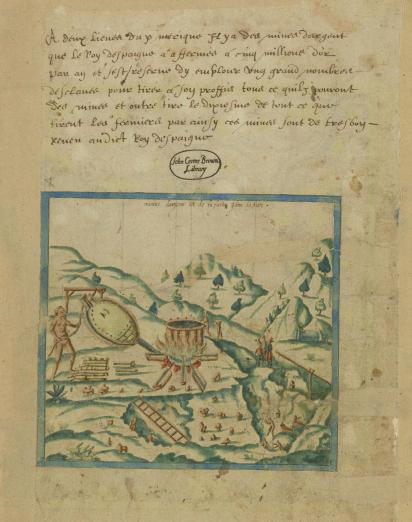

Samuel de Champlain, Mines d'argent et de la facon quon le tire, 1604

Spanish explorers discovered silver in the mountains north of Mexico City in the 1550s. Natives were forced into backbreaking labor in these mines, which produced much of the world's silver.

In the center of this image a Central Mexican Native powers a bellows. The fire he tends heats a crucible, transforming ore into the silver ingots that fueled the expansion and development of the Spanish Empire.

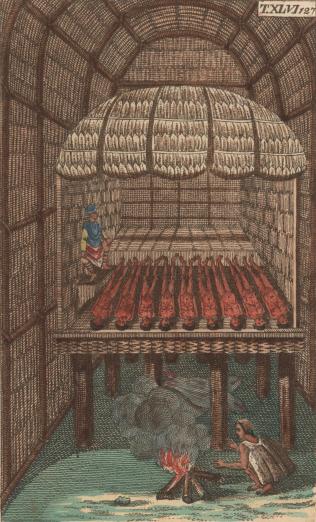

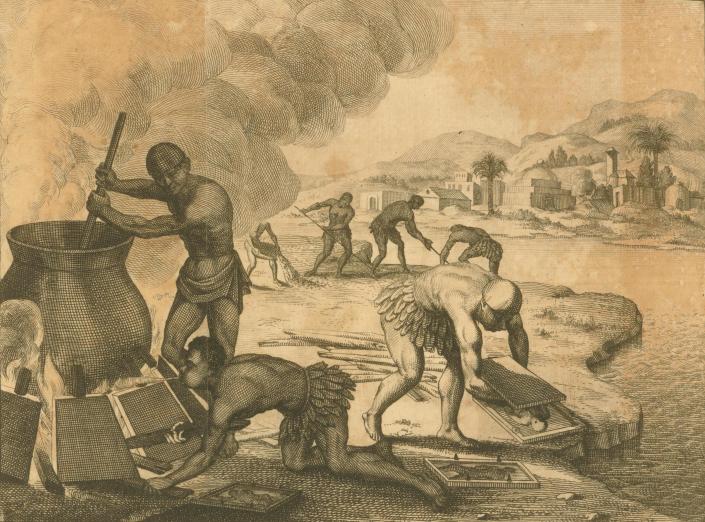

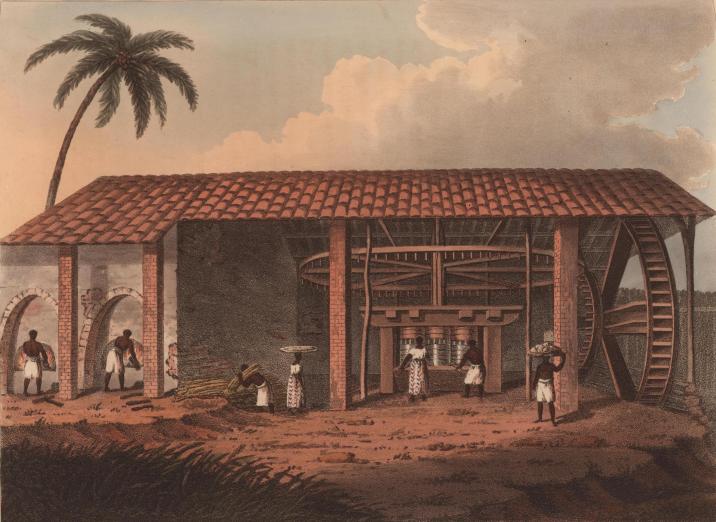

A Sugar Mill, 1816

Fire was an important tool in processing American natural resources. In the case of sugar plantations, fire was necessary to transform cane into sugar.

This process happened in the “house of fire” and usually employed skilled and loyal former slaves as it was a key phase of the production.

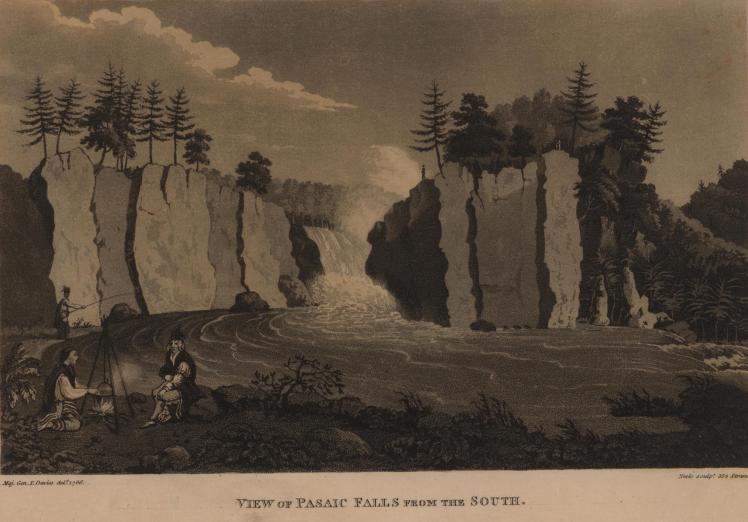

Maj. Gen. T. Davies, designer, and Neele, engraver, View of Pasaic Falls from the South, 1798

In this 1766 depiction of the Passaic waterfall in New Jersey, the scene of wild nature is domesticated by the cooking fire at bottom left.

The ferocity of the falls is tamed by the image of two indigenous inhabitants, cooking fish and smiling in the evening shadows. Although the falls were once a habitation for the Lenape people, the power of the waterfall and its potential domestication for industrial use would soon attract the attention of U.S. settlers, who founded the town of Paterson, New Jersey beside the falls in 1791.

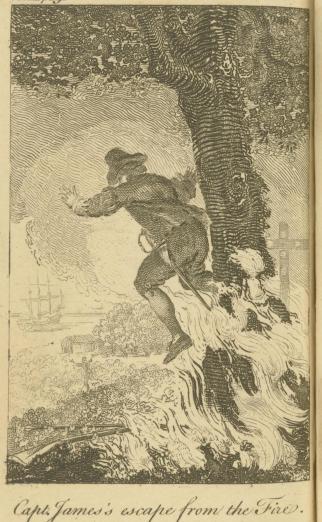

Capt. James's escape from the Fire, 1760

The Welsh sea captain Thomas James was just one of the many Europeans to fruitlessly search for a Northwest Passage through North America. Having failed to find a passage across the continent, Captain James – shown here in 1632 – and his men managed to survive the winter on the shore of James Bay, at the southern end of Hudson Bay. Spring allowed him to resume travelling, and Captain James attempted to signal any Native peoples who might be nearby to provide aid.

When his assistant started a fire prematurely, Captain James was nearly trapped in the tree he was using as an observation post and was forced to leap to safety. In the wilds of the Americas, fire could quickly slip out of the control of even the most resourceful of men.

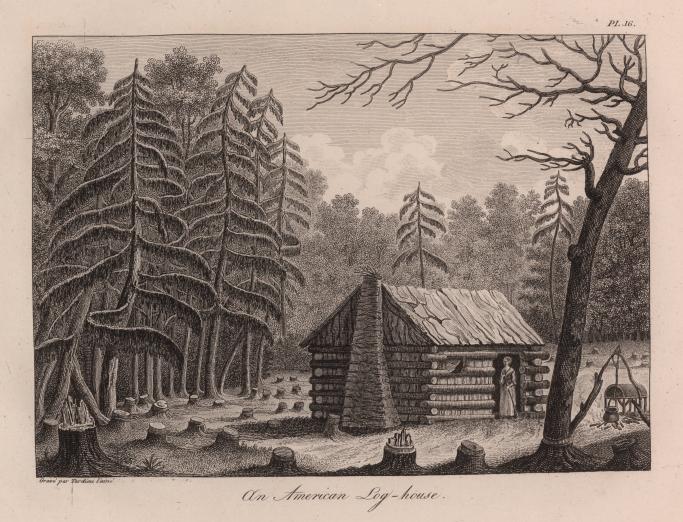

Tardieu l'ainé, engraver, An American Log-house, 1826

This image of North American frontier domesticity, from somewhere in the Ohio or Mississippi Valleys, was recorded by French general Georges-Henri-Victor Collot in the 1790s. The clearing has been made by girdling the trees, a technique commonly used by Native Americans, in which a strip of bark is removed from the circumference of the tree. It is a slow, but inexorable process, not unlike the incursion of European settlement across the continent.

The cooking fire on the right side of the image completes this scene of human control over the wild American environment.

Fire as Foe

As much as fire has aided humankind in myriad ways, it remains a force capable of tremendous destruction. Natural fires in the form of volcanoes and prairie fires contributed to an ever-evolving landscape. And yet, while sometimes constructive, these natural processes could be utterly devastating to human endeavors. The Americas are geologically far more active than mainland Europe, and fire and ash often poured over the settlements and ambitions of people and their communities. Fire was also wielded by people who themselves deployed it for destructive purposes. Canadian Natives burned French trade goods in an effort to oppose intrusions into their territory. Conversely, the threat of torture with fire by Natives of Louisiana frightened potential settlers in that region. European pirates and privateers used fire to destroy the settlements of other Europeans as they fought for control over the landscape and riches of the Americas.

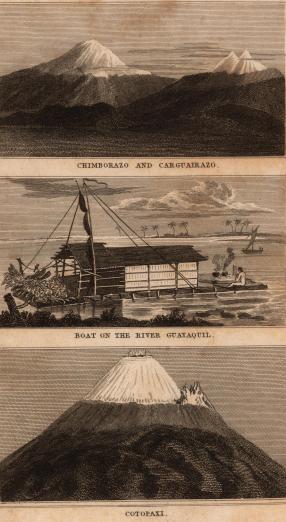

Chimborazo and Carguairazo [Top]. Boat on the River Guayaquil [Middle]. Cotopaxi [Bottom], 1820

American nature astonished European visitors, who believed that it would be a source of endless income. Yet sometimes that same extraordinary nature also represented the treacheries of colonization, as in the case of volcanoes like the famous Chimborazo in Ecuador.

The Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt attempted to climb Chimborazo alongside his French companion Aimé Bonpland and the South American Creole Carlos Montúfar.

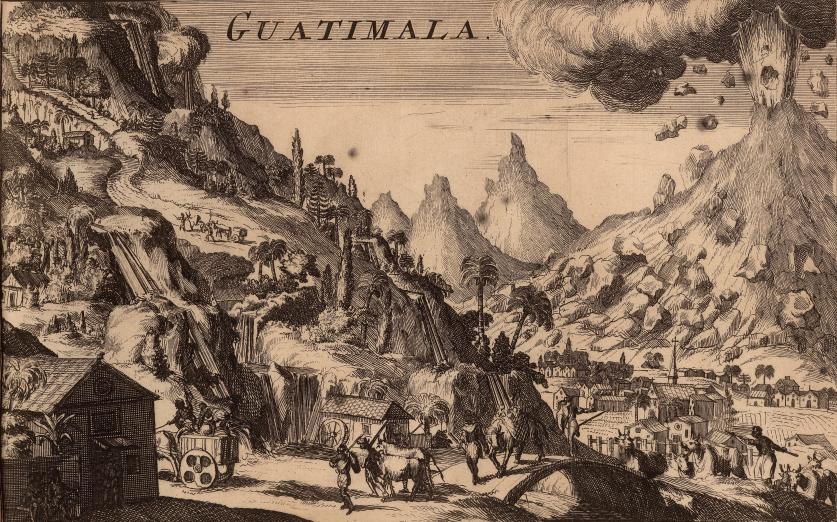

Guatimala, 1694

The Americas are far more volcanically active than mainland Europe. A volcanic eruption in Guatemala shows how volcanoes in America often represented a significant danger to colonial settlements, town dwellings, and human activity, symbolized here by ox carts driven by Native peoples.

Fire could well up from underground with devastating consequences.

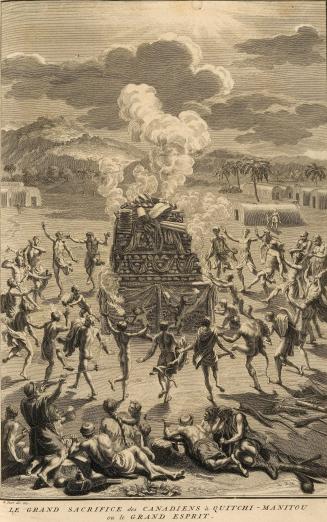

Bernard Picard, Le Grand Sacrifice des Canadiens à Quitchi-Manitou ou le Grand Esprit, 1723

The text accompanying this image describes how the Native peoples of Canada made sacrifices to their supreme being not by burning live animals, but rather goods they traded with the French.

The scene shows how Native peoples of the Americas saw danger in European colonization, which is represented by the new artifacts they introduced to America through trade.

Fire in this scene serves both to destroy these representations of French incursion and to facilitate requests for divine intercession.

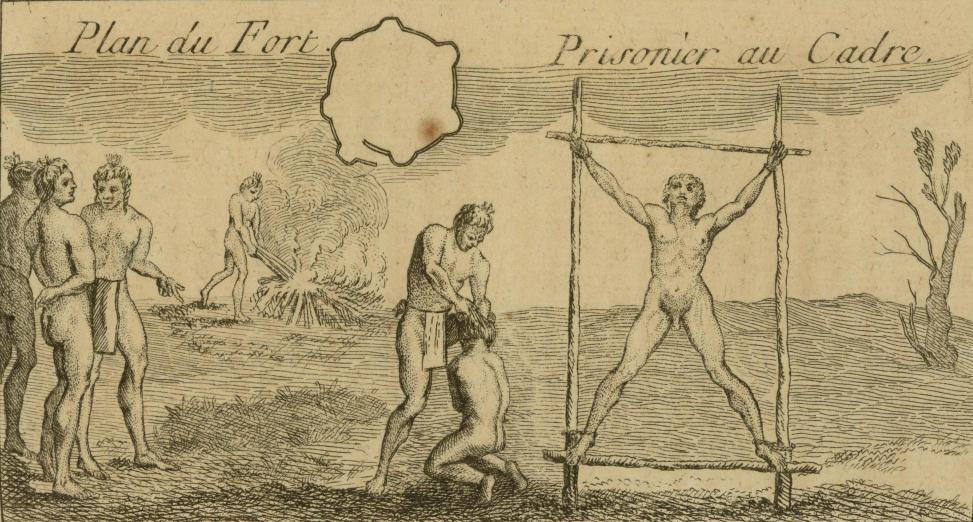

Plan du Fort. Prisioner au Cadre, 1758

Antoine-Simon le Page du Pratz went to Louisiana as part of an early-eighteenth-century scheme to bolster colonization and trade in the region. Scottish economist and entrepreneur John Law had proposed a plan to settle the area funded by the sale of shares in the Company of the West. The company itself failed (and Law was ruined financially in the process), but the settlers remained.

To defend themselves from Native residents of the region, the settlers built a fort, depicted at the center of the image.

The rest of the image depicts the stages of torture and execution of a prisoner at the hands of the Native populations. Prior to being tied to a scaffold, the prisoner is scalped as an individual in the background ignites branches in a fire, perhaps for further torture. With the prisoner so completely exposed, one shudders at the fate that awaited him when the fire was ready.

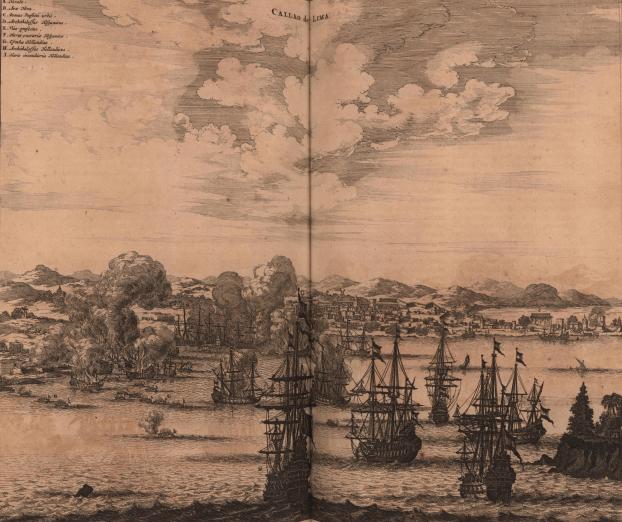

Callao de Lima, 1671

This image from 1671 recounts an attack during the previous century by Sir Francis Drake, in which the English privateer sacked Callao, Spain's most important Pacific port. The engraving depicts numerous ships ablaze.

Naval vessels were always at risk of fire, though it is unclear if Drake actually set fire to all the ships in harbor or if the artist used fire to convey the severity of Drake's raid. Drake's attacks ended the Spanish monopoly on the Pacific. Regardless of how the attack on Callao unfolded, the dream of the Pacific as a Spanish lake had gone up in smoke.

John Russell Bartlett, "Prairie on fire from the Rio Grande to Corpus Christi, Texas", 1852

Following the Mexican American War (1846-1848), Providence-born John Russell Bartlett was tasked with surveying the new boundary between the United States and Mexico. Bartlett saw the American Southwest as a land of great commercial potential for American settlers. But this new land was not without its dangers. Many Native peoples, resistant to U.S. incursion, populated the region, and the landscape itself could be hostile. Out on this new frontier fire was an uncontrolled force of nature, resistant to human control. Prairie fires of tens of thousands of acres were a terrifying force to unprepared settlers.

Fires of Resistance

The colonial era drew to a close in the conflagrations of the wars of independence, from the late eighteenth- through the early-nineteenth centuries. Across the Americas, fire symbolized the upheaval of revolution, but it also played a more literal role as a tool of warfare. In this final section, we see fire as a representation of unrest in the British North American colonies, as a destructive consequence of warfare in New York, and as a mark of the transition of power from European to American hands in Haiti. In the exhibition’s final image, Haitian leader Henri Christophe stands before burning colonial buildings wielding power in the form of fire. In the guise of a flaming torch, power was symbolically passed – or, more accurately, wrenched – from Europe to the Americas.

America in Flames, 1775

Both the continent and nation of America have a long tradition of being represented by the image of a woman. In this allegorical depiction of revolutionary unrest in the British colonies, America appears as an old woman amid flames of discontent caused by the administration of Lord North.

Above America, former British Prime Minister John Stuart feeds the flames of the American conflagration with a bellows, as does William Murray, first Earl of Mansfield. Lord North, the central target of the cartoon, stands to the side with yet another incendiary act protruding from his pocket, the Boston Port Bill, which blockaded the port of Boston.

The efforts of those trying to extinguish the flames are proving ineffective. The colonies are ablaze.

François Xavier Habermann, engraver, Representation du Feu terrible a Nouvelle Yorck, 1776

Although the cause of the fires was never clearly established, flames erupted in New York City on the nights of September 20 and 21, 1776. British soldiers blamed patriot arsons while patriots accused the British of causing the fires. In total, these fires destroyed about one third of the city, and marked a turning point from Patriot to Loyalist control of New York.

In this image, men in blue coats beat a man dressed in red, while Black slaves attempt to save valuables from the conflagration.

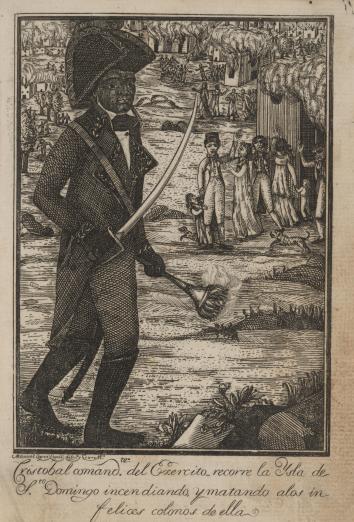

Manuel Lopez Lopez, designer and engraver, Cristobal comand. del Exercito recorre la ysla..., 1806

During his first voyage to America in 1492, Columbus arrived on the island of Hispaniola. Three hundred years later, the French colony of Santo Domingo on the western side of that island rose up in the only successful slave revolt in world history. The Haitian Revolution that took place from 1791 to 1804 shocked much of the Atlantic World because of its violence and its demonstration that the subordinate populations of the colonial world could overthrow their masters.

The image portrays former slave Henri Christophe, who organized the rebellion in the north of the island, carrying a torch and sword. In the background, people flee burning dwellings. Fire has been taken under the control of the slaves and is being deployed against the masters. Henri Christophe became Haitian president in 1807.

Related Events

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

Credits

The John Carter Brown Library would like to acknowledge and thank Jake Frederick (Lawrence University, USA) and Júnia Furtado (Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil) for guest curating "The Americas on Fire."