Antonio Ricardo: A 16th Century Printer on Both Sides of the Equator

In the late 16th century, the era of mechanical reproduction of texts dawned in South America. When Antonio Ricardo’s first book-length product emerged from his press, the title page did more than announce his name–it proclaimed his pioneering status as the “first printer in these Kingdoms of Peru.”

Behind the Hispanicized name ’Ricardo’ lay the story of an Italian-born journeyman. With a network spanning Italian, French, and Spanish printing circles, he embarked on a transatlantic venture around 1570. Mexico City became his new home, where he would end up establishing his own printing office (active 1577-1579) and gaining valuable experience. Here, Ricardo honed his craft printing Indigenous language texts and forged crucial connections with the Jesuit order, producing several works for them.

Ricardo's Jesuit connections may have sparked his next bold move. As the order advocated for a printing press in Lima, Ricardo saw an opportunity in the wealthy southern viceroyalty. However, the relocation posed significant challenges. Being a foreigner, he needed special authorization—a bureaucratic hurdle compounded by the practical difficulties of transporting his craft. A printing press, after all, meant hauling hundreds of pounds of specialized equipment across vast distances. Undeterred, Ricardo set sail from Acapulco with his precious cargo in 1580. His journey to Lima was far from smooth, marked by an extended stop in Nicaragua where he had to extricate himself from legal troubles with quick wit and persuasion.

In Lima, Ricardo’s press initially churned out modest fare—religious images, primers, and playing cards. It wasn’t until 1584 that he received permission to print books, opening the door to more ambitious projects. As his team diligently set type for sections of the groundbreaking Doctrina Christiana, fate intervened with an unexpected commission.

A consequential shift in timekeeping was underway. As Spain adopted the Gregorian calendar, the Audiencia de Lima tasked Ricardo with an urgent job: to print a decree ordering the elimination of ten days from the calendar—October 4th would leap to October 15th—thus aligning the American viceroyalties with the new system and ensuring the proper timing of Easter and other movable feasts.

The result of this rushed commission was the Pragmática de los diez días del año, dated July 14, 1584. This document holds a unique place in history: it stands as the earliest known printed work from a South American press. In a twist of historical irony, amid the profound political, social, and religious upheavals of European colonization, Peru’s first printing press was inaugurated with a decree that altered time itself.

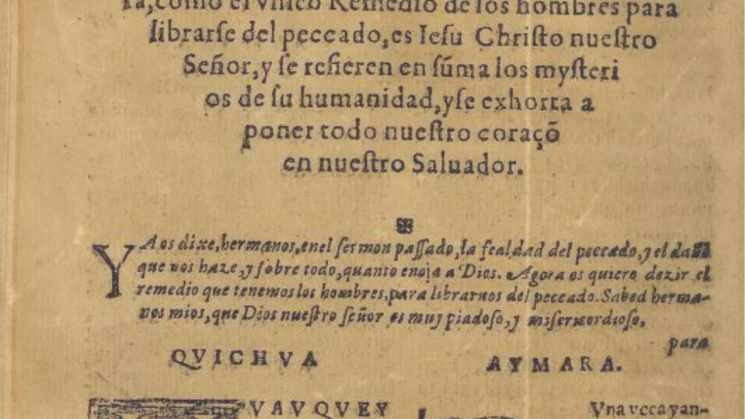

With the Pragmática inked, pressed, and dispatched across South America, Ricardo turned his attention back to the Doctrina Cristiana. This monumental work, commissioned by the Third Council of Lima, was a collaborative effort of priests and friars, with intellectual figures like José de Acosta at the helm. In Ricardo's workshop, skilled compositors faced the challenge of setting type for three languages on each page. Spanish appeared in a central column, followed underneath by parallel columns of Quechua and Aymara—a visual representation of the cultural and linguistic convergence and struggle unfolding in the Andes.

The Doctrina Christiana inaugurated a pivotal trilogy of texts. As the first in a sequence of three works, it led a concerted effort to spread Christian faith, standardize its preaching, and displace the ancient religions of Indigenous peoples. The Confessionario para los Curas de Indios (1585) and the Tercero Cathecismo (1585) followed, each adhering to the innovative trilingual format.

These works were deployed as powerful instruments of cultural change. Today, they stand as crucial artifacts, offering invaluable insights into the transformations reshaping the Andean world and beyond during this early period of colonization. Through these pages, Antonio Ricardo's legacy as a master printer became inextricably linked with the almost unfathomable cultural shifts of 16th-century South America.

* When I wrote a blog post about the JCB collection of early Mexican imprints, I said I would prepare another text, also focusing on the sixteenth century, but about our Peruvian books. The story you just read is the announced post. Thank you for taking the time to read it.