The British invasions of Rio de la Plata

The JCB has long been an exceptional rare book library for the study of the British invasion of the Rio de la Plata (1806-1807), a series of failed British military campaigns that played a significant role in the rising momentum of Argentinian and Uruguayan independence movements, and, in a counterintuitive way, laid the groundwork for British commercial dominance in South America in the latter 19th century.

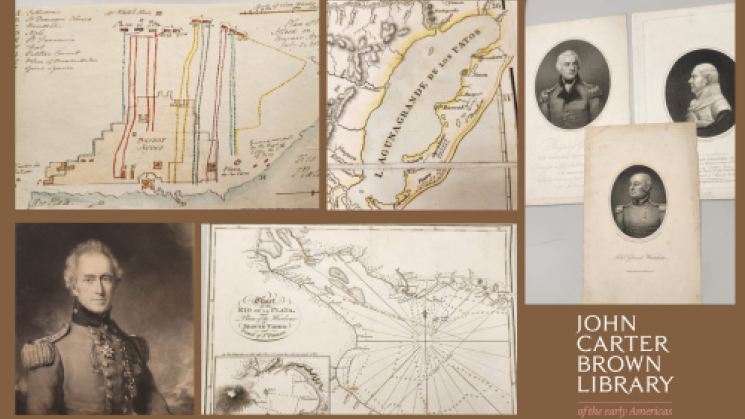

In 1969, the JCB acquired at auction an extraordinary composite atlas of 28 unique manuscript maps and views of these British campaigns, a collection that originally belonged to Sir Thomas Phillipps, the famed 19th century collector of manuscripts. All of the maps and views in this atlas have been digitized, and continue to assist in supporting new research on these invasions.

Now, in early 2024, we’re happy to announce two new exciting acquisitions that support this research even further. The first is a large format, hand coloured, printed map by Aaron Arrowsmith, one of the most prominent British cartographers of his day who excelled at producing detailed, large format maps. Arrowsmith published “A Map of Part of the Viceroyalty of Buenos Ayres” in November, 1806, five months after the first British invasion of that city, and three months before the second invasion.

The second new acquisition is another remarkable document collection, this one combining manuscript and printed materials. The collection bears witness to the British military campaigns in the Rio de la Plata and offers a fascinating perspective on events as they unfolded in 1806.

So what did transpire over the 14 months of the campaigns that had such far-reaching consequences? For well over a century, the British had sought a foothold in the Spanish Americas, and the Rio de la Plata had been identified multiple times as an ideal region for the expansion of British imperial commerce through the forced opening of new overseas markets for British merchants. These British and Spanish imperial tensions grounded in their commercial rivalry had been gaining particular momentum in the final decades of the century. The context of the Napoleonic wars in which the British were antagonists to both France and Spain gave the British a new set of military justifications to frame such an invasion, and the British were, in particular, emboldened by their recent victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

The first invasion attempt was the result of an expedition launched by Commodore Sir Home Riggs Popham but, as it happens, was technically unsanctioned by the British Prime Minister William Pitt. The British occupied Buenos Aires on 27 June, 1806 under the command of General William Carr Beresford; the city had been left almost defenseless because Spanish troops had been deployed to Montevideo and to Upper Peru (Bolivia) to defend Spanish settlements from a revolt led by Tupac Amaru II. The Spanish Viceroy Rafael de Sobremonte fled in the face of the British, in a move that would have long lasting consequences by rendering him deeply suspect in the minds of the city’s residents. On August 4, French-born Santiago de Liniers led the defense of the city, approached it with a military force of troops from both BA and Montevideo and successfully seized control, ousting the British with Beresford surrendering on Aug 14. Sobremonte was deposed as Viceroy, de Liniers was put in his place, and a mixed military force of local and Spanish troops was formed to ward off a potential second invasion.

The second invasion came months later, in the wake of a new British occupation of Montevideo across the mouth of the Rio de la Plata. In February 1807, Montevideo was besieged by a joint British force made up of a naval squadron led by Admiral Sir Charles Stirling and a military squadron led by General Sir Samuel Auchmuty, and the city fell only hours later. General John Whitelocke was appointed to lead the combined British forces in the city, and launched the second invasion of Buenos Aires from Montevideo in July. However, although he was able temporarily to hold certain neighbourhoods, he failed to take the city, greatly underestimating the impact of urban guerilla warfare. Whitelocke was defeated later in the month and, somewhat unbelievably, signed an armistice that included withdrawing British troops from the entire Rio de la Plata, including those stationed in Montevideo: the entire British operation had failed.

This pivotal moment in the history of European imperial competition in South America has multiple intersecting meanings: certainly there is the military story of an early failed British attempt to draw a rival South American region into their imperial commercial sphere. But arguably more important is the story of how the failed invasions and military occupation bolstered local creole military and political elites with explosive implications for the growing nationalist movement in the colony. The flight of Sobremonte (and the abandonment of the colony by the Spanish that it symbolized) combined with the successful formation of a mixed military force reliant on local troops with creole leaders at the head: this explosive combination furthered ambitions for independence that culminated only a few years later in the May Revolution of 1810.

However, in a turn of events that clearly echoed the global commercial consequences of the earlier American War of Independence of 1776, these British military failures did not spell the demise of British commercial hopes in the region. In fact, they had rather the opposite impact: within a few decades, as a result of treaties signed with the republics created after the independence of Argentina (1815) and Uruguay (1828), Britain finally gained the commercial foothold in the Southern Cone that it had long sought, in a move that helped cement its 19th century dominance of global trade.

The JCB’s second new acquisition brings researchers into the heart of these events; it includes a ca. 1806 manuscript map of the British troop movements during the second invasion of Buenos Aires, a small printed map of the Rio de la Plata, and a series of military portraits of the British military leaders of the failed campaigns: the disgraced Lieutenant General Whitelocke, Lord Beresford (accompanied by a manuscript letter by Beresford), and Auchmuty’s second in command at the Siege of Montevideo, Major-General Sir Charles Broke Vere.

This collection joins the Arrowsmith map and the earlier-acquired collection of maps and views associated with these invasions: together this group of materials offers an unparalleled perspectives on these invasions ranging from manuscript maps that evoke the drama and immediacy of daily events, to a large format cartographic depiction of the scene aimed at the broader public, to the mid-19th century commemoration of military disgraces that took place across the South Atlantic Ocean, thousands of miles away from the seat of intensifying British geopolitical power.