Ginseng in Canada?

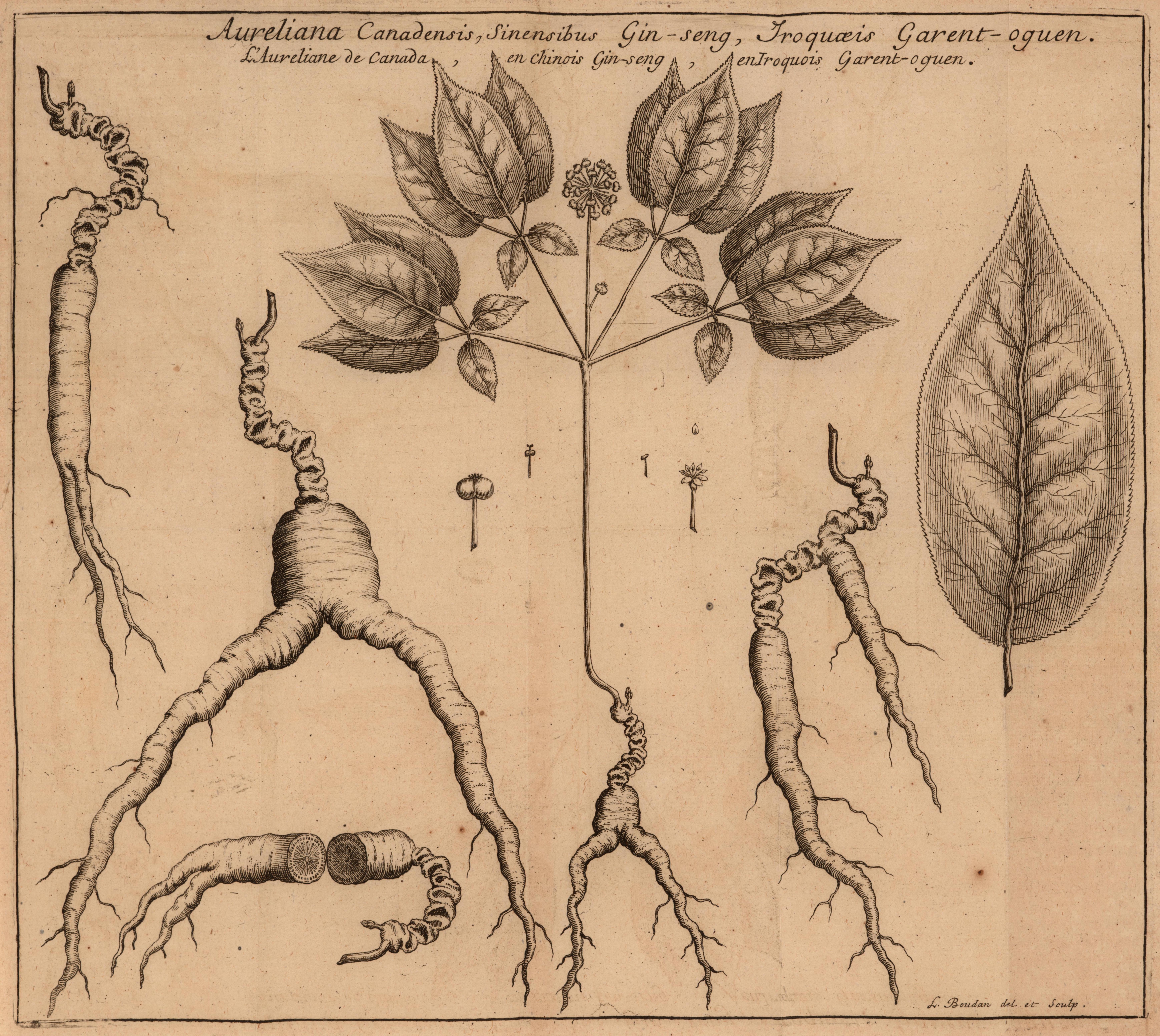

In 1718 Joseph-François Lafitau claimed to have discovered ginseng in Canada. Working in the mission to the Mohawk at Kahnawá:ke/Sault Saint Louis between 1712 and 1717, the Jesuit missionary had first heard of the plant that he would try to name Aureliana canadenis (a name rejected that same year by botanists at the royal garden in Paris) in a report from Jesuits working in China. In the 1713 volume of the Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, Pierre Jartoux had written about being one of the first Europeans to have witnessed the collection of ginseng in the region he called Tartarie [China] and he had provided a crucial visual and written description of the plant. Curiously, he also offered the suggestion that the same plant might be found in the French colony of Canada. Lafitau read Jartoux's account in the fall of 1715 and, using that information, he set out to see if the plant could be found in the area around his mission the following spring. Initially he had little success in spite of his efforts to question the aboriginal peoples to whom he ministered. It was only in the summer of 1716, after having given up in his search, that he finally noticed the plant; his attention was drawn by bright vermillion of its fruit. Lafitau seems to have immediately penned a mémoireon the plant that he sent (along with physical specimens he had preserved in eau-de-vie) to Paris where it was read by the Académie royale des sciences in January of 1717. Although Lafitau seems to have thought that his findings were self-evident, he met with a great deal of initial scepticism at the Académie.

The 1718 Mémoire présenté à S. A. R. Mgr le duc d'Orléans... concernant la précieuse plante du gin-seng de Tartarie, découverte en Canada par le P. Joseph-François Lafitau must then ultimately be looked at as Lafitau’s effort to recover his reputation and prove beyond the shadow of a doubt that the Canadian and Chinese plant were one and the same. Marshalling linguistic, anthropological, medical, and botanical evidence to his cause, the result was a work that claimed that the plants were the same because the cultures that used them–the Chinese described by Jartoux and the Iroquois with whom Lafitau had lived–shared a common understanding of the plant. He proved his claim primarily by analyzing the etymology of the words Garent-oguen and Gin-seng by which it was known in each culture. Although it provided the basis for what would become a flourishing commercial exchange between Canada and China in the following decades, Lafitau's work seems to have been viewed with scepticism by many botanists who ignored his work completely once surer botanical information became available. Rightly so, it may seem, as American and Chinese ginseng are in fact different species of the genus Panax. Lafitau himself seems to have left this topic behind as he focused more exclusively on the cultural similarities between New and Old World non-Christian cultures in his 1724 book, Moeurs des sauvages amériquains comparées aux moeurs des premiers temps, where ginseng makes only the briefest appearance.

Chris Parsons, August 2008