Spain’s Florida was both larger and smaller than the present state. From New Spain to Newfoundland, everything west of the Atlantic coast was once known as “Terra Florida.” Finding no silver, no way to the Orient, and only pockets of potentially tributary Natives, Spaniards directed their settling impulses elsewhere, leaving their northern frontier in the hands of career soldiers, missionaries, and colonized Natives.

The captaincy general of Florida, established in 1565 in response to a French challenge, had the entire Southeast as its sphere of influence, but its mission provinces were limited to the upper half of the Florida peninsula and what is now the Georgia coast. St. Augustine, positioned to guard the strategic Florida Channel, was maintained at royal expense as Spain’s rivals circled ever closer. The English founded Carolina, creating an avid market for indigenous slaves; the French descended the Mississippi and founded Louisiana, which Spain countered with Texas and Pensacola. In 1762 the British captured Havana, important to the Spanish tobacco monopoly. To get it back, Spain traded Florida for Havana in the Peace of 1763.

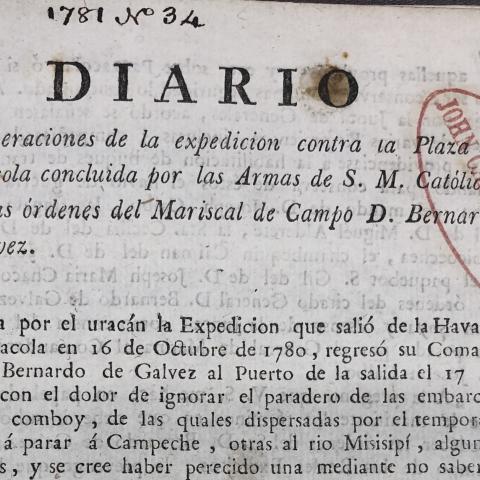

The British divided their prize into two provinces, East and West Florida. They offered land on easy terms to speculators and extended the Proclamation Line of 1763 to keep Natives and white colonists apart—Natives to the west, white colonists to the east. But the American Revolution threw the Floridas into chaos as thousands of Loyalists arrived with their slaves to claim sanctuary on British soil. After Yorktown and Bernardo de Gálvez’s recapture of Pensacola in 1781, the British ceded the Floridas back to Spain. Again, most of the non-indigenous population departed.

For the long years when few were taking notice of it, Florida continued to be affected by what happened in the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico. Indeed, it is impossible to tell the story of early Florida without reference to this larger context. What the exhibition shows is how quickly Spain’s enemies took their side of the Florida story to the court of public opinion and how slowly Spain did. With the most important Spanish primary sources remaining in manuscript until the mid-nineteenth century, it is no wonder that the initial historiography of early Florida assumed an anti-Catholic, anti-Spanish character.

Credits

This exhibition was curated by Amy Turner Bushell and Susan Danforth.