In seventeenth and eighteenth-century Europe, girls and women were encouraged to take up natural history as an educational and leisurely pursuit. In late eighteenth-century England especially, botany was increasingly regarded as an appropriate female activity that would stimulate moral and spiritual improvement. Most women studied local or European flora and fauna. However, there are some who travelled across the Atlantic as part of imperial networks – often as wives or daughters of navy officers, colonial administrators, or diplomats – to explore the natural history of places such as Surinam, Mexico, Antigua, and Brazil. Others remained in Europe but studied the plants and animals of the Americas through transatlantic correspondences or travel accounts.

This exhibition at the John Carter Brown Library explores the rich variety of ways in which European women contributed to the creation and dissemination of botanical and zoological knowledge of the Americas. From the collection, cultivation, and study of plants and insects to the production, translation, and illustration of travel journals, women were important contributors to the development of this scientific area of study that flourished in the context of empire.

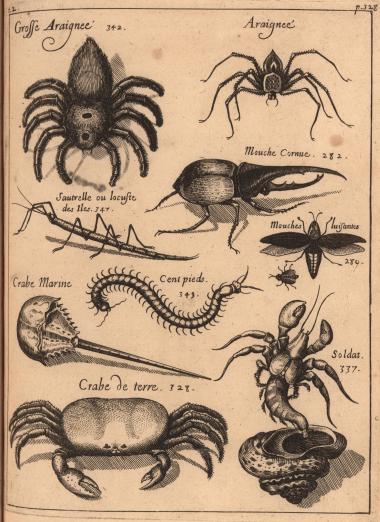

Insects in the Americas

In the 16th and 17th centuries Europeans began to turn to insects as a new field of study. This was further stimulated by the work of, among others, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), who used the microscope to study the morphology of insects, and Jan Swammerdam (1637-1680), who made important discoveries on the anatomy of insects. European interest in insects also grew because of the increasing number of travellers bringing back zoological specimens from overseas voyages of exploration. The JCB houses the works of Virginia Ferrar (1627?-1688) and Maria Sibylla Merian (1747-1717), two European women whose captivating work on insects both reflected and shaped this unfolding field.

Virginia Ferrar

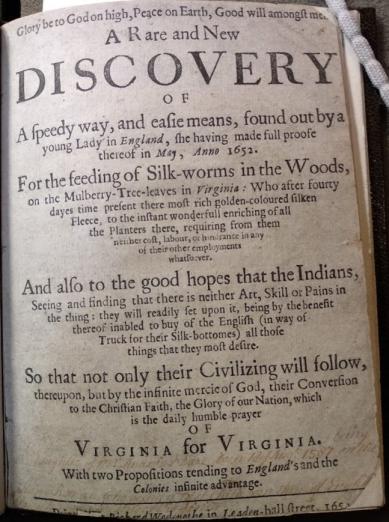

Virginia Ferrar (1627?-1688) was an English bookbinder and sericulturalist (someone who cultivates silkworms). She was named after the colony of Virginia; her father, John Ferrar, had been deputy of the Virginia Company of London, which sought to establish colonial settlements in North America. John Ferrar aimed to stimulate a silk industry in Virginia, and so he encouraged Virginia to the cultivation of silkworms from their family home in England. Virginia also corresponded with Virginians, some of whom would send her silkworm cocoons from the colony. The JCB holds several books related to Virginia and John Ferrar’s work on silkworms. These books provide a fascinating glimpse into the life of a seventeenth-century female sericulturalist and her participation in transatlantic networks of knowledge exchange. See this image here.

Keen to find out more about the feeding habits of silkworms, Virginia Ferrar designed an experiment to see whether caterpillars developed differently when fed mulberry leaves (their preferred food) on trees in the garden as opposed to in indoor cabinets. John Ferrar carefully documented the methods and results of the experiment in a letter, which he sent to Samuel Hartlib. Hartlib published the letter in 1652 in a work titled ‘A Rare and New Discovery of a speedy way, and easie means, found out by a young Lady in England […] For the feeding of Silk-worms in the Woods, on the Mulberry-Tree-leaves in Virginia’. This is considered one of the earliest studies on the Virginian silkworm.

In 1655 a revised edition of this work appeared under the new title of ‘The reformed Virginian silk-worm’. An ‘Advertisement’ signed with Virginia Ferrar’s initials ‘V.F.’ was included in this new edition and shows that she exchanged letters and materials related to silkworms within an international community of sericulturalists. The extent to which John Ferrar influenced or even dictated this correspondence, however, remains disputed.

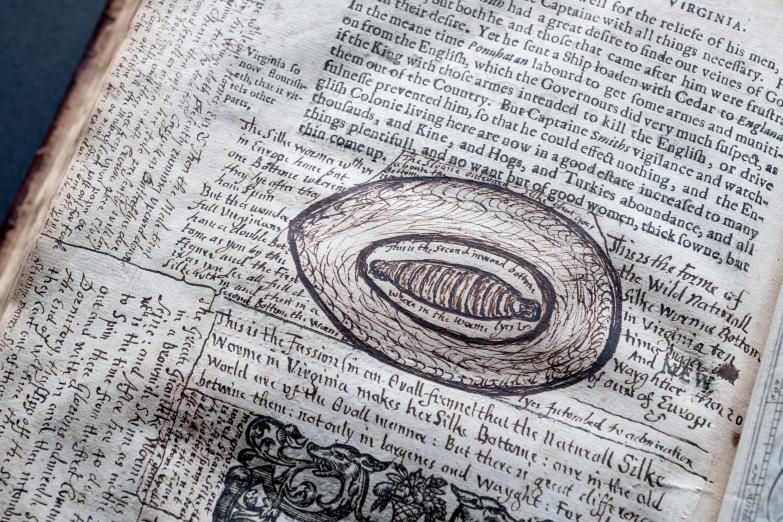

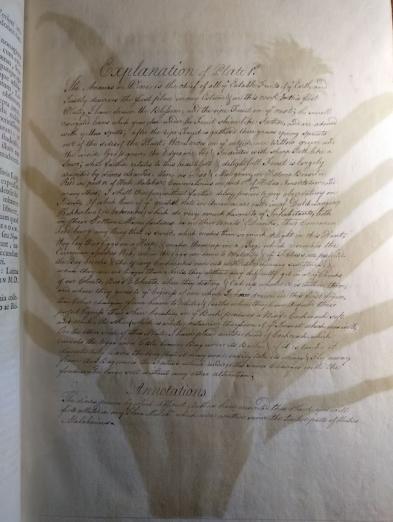

The JCB also has an annotated copy of Gerhard Mercator’s Atlas previously owned by the Ferrar family. Crammed into the margins of the atlas are a large number of handwritten notes and drawings on silkworms that scholars have attributed to either Virginia and John Ferrar or to John Ferrar exclusively. The annotations highlight the value of this atlas as a material object functioning as a space for learning, reflection, and possibly female participation in seventeenth-century scholarly debates on the natural world.

Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) was a German-born naturalist and scientific illustrator. Merian held a lifelong fascination for insects. From the age of thirteen, she collected and bred caterpillars, studying their behavior and transformation into moths and butterflies. In 1699, she travelled to the Dutch colony of Suriname with her daughter to further her entomological research. For two years Merian travelled, collected, studied, and sketched, until ill health forced her to return to Europe.

See this image here.

She published the results of her research in the Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705), which contained 60 copperplates and accompanying descriptions of the insects and plants of Surinam. Many of the insects she described were new to Europeans, and she was the first naturalist to depict insects and their host plants together in one composition, making this one of the earliest tropical ecology studies. She is still admired today for her scientific contributions and the exceptional artistic quality of her work.

The 1705 edition of the Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium was published in both Latin and in Dutch. It was reprinted in 1719, two years after Merian’s death. The JCB holds three copies of the 1719 edition, two in Latin and one in Dutch. This edition contains 12 additional engraved plates. Merian’s illustrations of butterflies and moths were unique for capturing the different stages of their metamorphosis – caterpillar, cocoon, butterfly or moth – in a single image. Even after 300 years, the eye for detail (look at how the caterpillar has been chewing on the leaves!) and the vibrancy of the colours are breath-taking. See this image here.

Until the nineteenth century, illustrations were usually printed in black and then colored by hand. For the 1705 edition of the Metamorphosis, Merian and her two daughters colored many of the plates themselves. In later editions this work was done by colorists. The quality of the coloring varied greatly. Buyers could also decide to leave the illustrations uncolored.

The three copies in the JCB showcase the uniqueness of each copy. Copy 1 is uncolored, and in copies 2 and 3 the coloring and shading are subtly different. Copy 3 is also a mirror image of the other two copies. This is because Merian pioneered a printing technique called counterproofing. In a counterproof, the outlines of the image are softer and there are no platemarks on the page, which makes it look more like an original watercolour.

From left to right: Merian, Maria Sibylla. Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. Latin edition (1719) c.2; Latin edition (1719) c.1; and Dutch edition (1719).

One of the JCB’s Latin copies of the Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium has many extensive handwritten annotations. The annotations are full English translations of the Latin text accompanying each plate. It is unclear who made these translations or when they were added, but it provides insights into how readers in the past interacted with Merian’s books and how they were used as tools in the study of insects.

The Flora and Fauna of the Caribbean

In the late eighteenth century it was not uncommon for elite and middle-class British women to accompany male relatives, often plantation owners or Royal Navy officers, on journeys to the British colonies in the West Indies. Curious to learn more about their new surroundings, some women set about studying, collecting, and recording the native flora and fauna of islands such as St Kitts, Jamaica, and Antigua. The JCB holds the natural history works of Maria Riddell (1772-1808) and Lydia Byam (baptized 4 September 1772 - ?), two eighteenth-century women who contributed to European botanical and zoological knowledge of the West Indies.

Maria Riddell

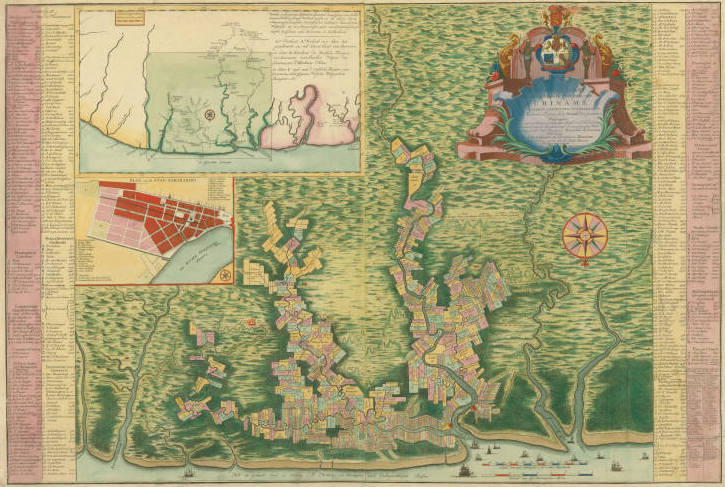

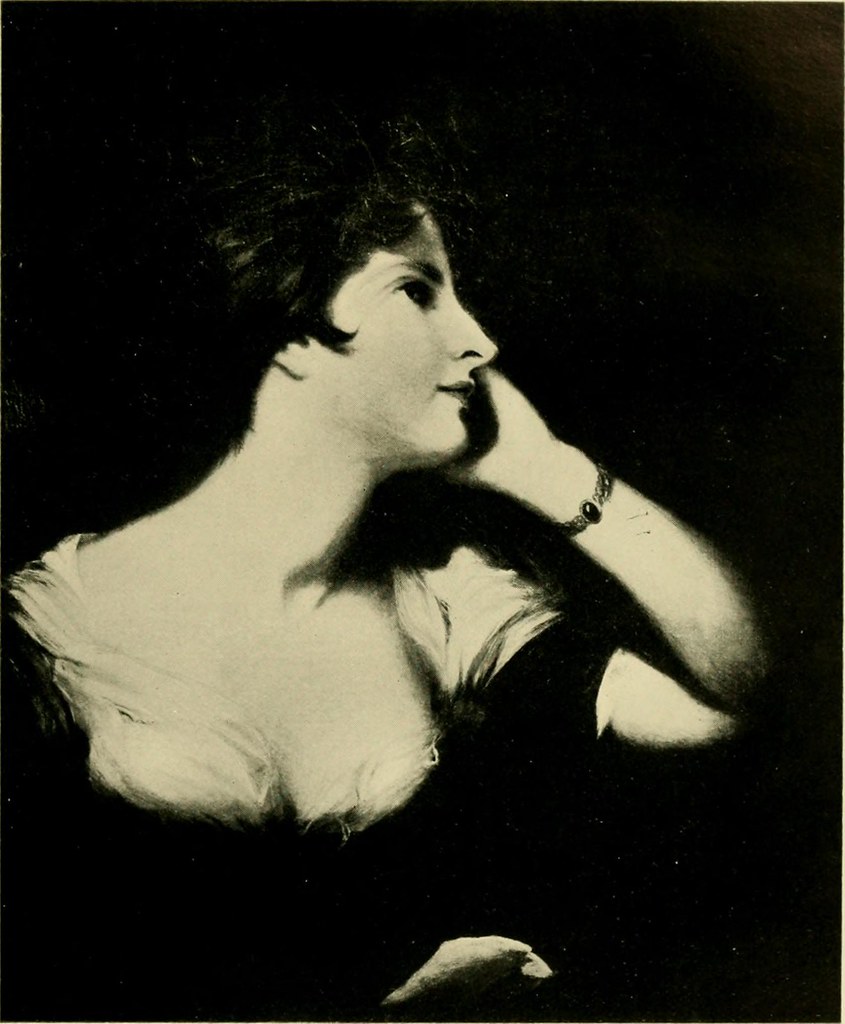

Maria Riddell (née Woodley, 1772-1808) was a British poet. Her father was a West-Indian plantation owner and governor of the Leeward Islands. In 1788 she travelled there with her parents, and in 1790, at the age of seventeen, she got married on St Kitts to Walter Riddell, lieutenant and plantation owner on Antigua. As a result of her travels Riddell published Voyages to the Madeira and Leeward Caribbean Isles: with sketches of the natural history of these islands (1792). Part travel journal, part natural history, the book gives a detailed and lively account of the flora and fauna of the Caribbean. Riddell was one of the first women to publish on the natural history of this region, and her account was lauded for its scientific detail and accuracy.

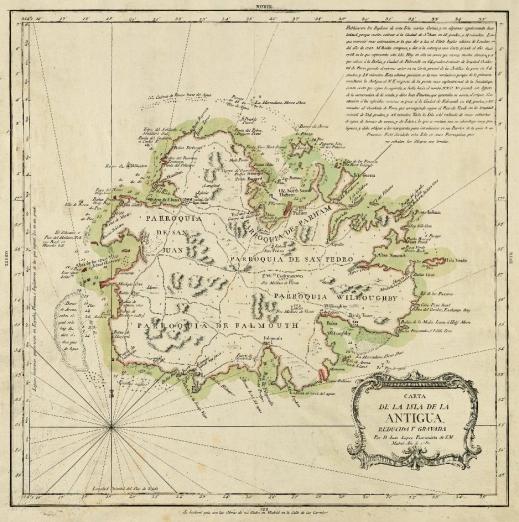

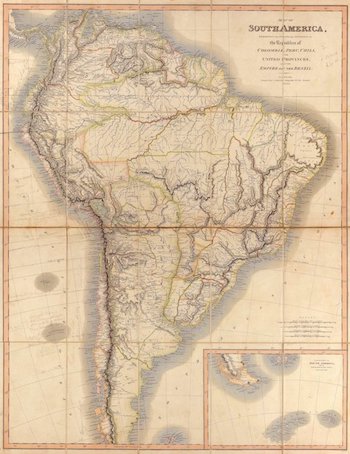

In a section titled ‘Sketch of the Natural History of Antigua’, Riddell provides a scientific description of the plants on that island. She used the classification system of Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus to identify and categorize her findings. Listed in alphabetical order, entries contain extensive information on the appearance, flavour, and usefulness of a wide variety of plants. She probably gained a lot of botanical information from discussions with local inhabitants. With the publication of her book this local knowledge was mediated to European audiences. See this map here.

The ‘Sketch of the Natural History of Antigua’ also includes a scientific description of the different kinds of animals she encountered there. Since zoology was largely considered to be a male domain in this period, Riddell was challenging traditional gender roles with the publication of her work. She based her zoological descriptions not on Linnaeus’ classification system, as was customary at the time, but on that of naturalist and fellow countryman Thomas Pennant.

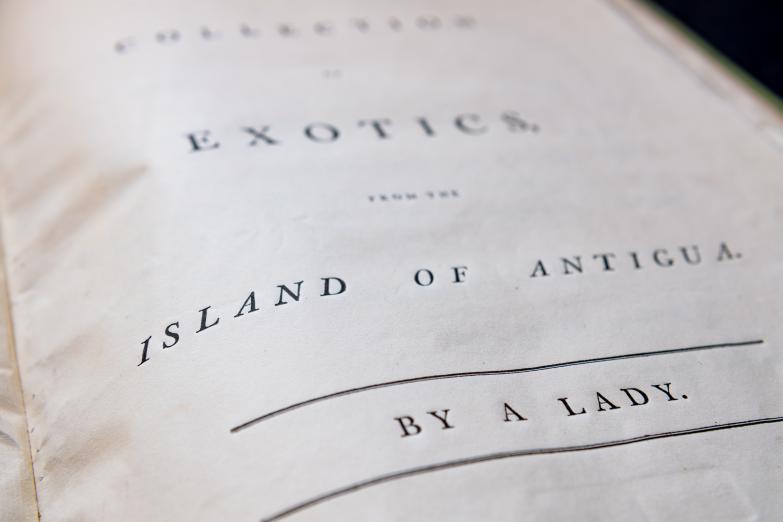

Lydia Byam (baptized in Antigua on 4 September 1772 - ?) produced two illustrated works on the flora of the West Indies: A collection of exotics, from the island of Antigua. / By a lady (1797?) and A collection of fruits from the West Indies: drawn and coloured from nature, and, with permission, most humbly dedicated to the Princess Elizabeth (1800). Little is known about Byam’s life, except that she was a member of the prominent slave-owning Byam family, who had a large sugar plantation on Antigua. Byam's works provide a rare and colourful insight into the natural history of the West Indies as seen through an eighteenth-century woman’s eyes.

A collection of exotics, from the island of Antigua was printed in London around 1797. Byam’s name does not appear in print; instead, the author is indicated as ‘By a Lady’. The work has been ascribed to Byam because the initials ‘L.B.’ were written in pencil on the title page of a copy held by another collection. The book consists of four pages of short botanical descriptions, followed by accompanying plates of hand-colored engravings. See this image here.

In 1800 Byam published A collection of fruits from the West Indies: drawn and coloured from nature, and, with permission, most humbly dedicated to the Princess Elizabeth. This work consists of nine hand-colored engraved plates depicting different fruits ‘drawn from nature’ and growing in the West Indies, such as the rose apple, avocado pear, cashew, and granadilla. Each plate has a caption identifying the plant. See this image here.

There are striking similarities between Byam’s and Riddell’s descriptions of Antiguan plants (replicated below). One possible reason for this is that they both used the Linnaean scheme for naming plants. Another explanation may be that Byam drew inspiration from Riddell’s work, which had been published only a few years previously. Could the two women have known each other? Riddell does record a visit to a Byam family on Antigua in her Voyages, but there is no mention of a Lydia Byam, and there is no other evidence to suggest that they crossed paths. Nonetheless, it is intriguing to imagine these two women as forming part of a larger female network of scientific exchange.

In Riddell (1792):

'The canella alba, or wild cinnamon, flourishes here with astonishing luxuriance. The leaf has a strong, spicy, aromatic taste; and the berries are delightfully fragrant' (pp. 86-87).

In Byam (c. 1797):

Canela alba; or, wild cinnamon.

The leaf of this luxuriant shrub, has a strong aromatic taste, and the flowers extremely fragrant (description to plate VII).

Sketches of Latin America

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, British merchants, diplomats, soldiers, and explorers travelled to Latin America in ever greater numbers. They travelled for different reasons: to fight in the independence armies of Simón Bolívar, to seek out mining or other commercial opportunities, or to explore the flora and fauna of places such as Chile, Brazil, Peru, and Mexico. Women would occasionally accompany male relatives on these long and often arduous travels. Unfortunately, very few women left written records of their travels, and even fewer published their accounts. The works that do exist, however, demonstrate that some British women engaged in botanical activities in Latin America. At the JCB we can find the works of two such women: Maria Graham (1785-1842) and Emily Elizabeth Ward (1798- 1882).

Maria Graham

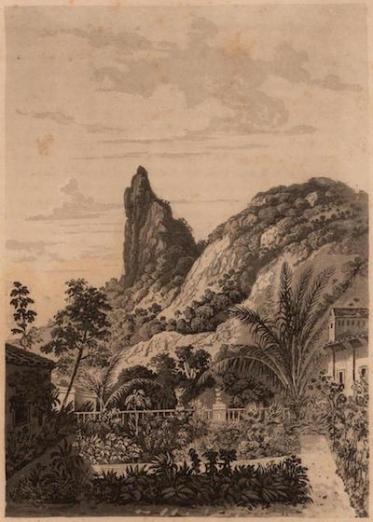

Maria Graham (née Dundas, later Lady Callcott, 1785-1842) was a British traveller and author. Graham travelled to South America in 1821 with her husband Thomas Graham, a Royal Navy captain whose job it was to protect British mercantile interests along the South American coast. In April 1822 Thomas Graham died en route to Chile. Although offered the opportunity to return home, Graham decided to stay in South America. She travelled extensively in Chile and Brazil for the better part of two years and continued her study of South American history, politics, and natural history. Botany forms a significant part of her resulting Journal of a Voyage to Brazil and Journal of a Residence in Chile, both published with her own drawings in 1824.

In 1821 Graham and her husband visited Teneriffe on their way from England to Brazil. Graham was keen to see the famous Dragon Tree at Oratava. Previous generations of naturalists had marvelled at its exceptional size and age. When Graham beholds the tree in 1821, however, it had recently lost half its crown. Describing the tree as ‘a noble ruin’, she writes:

‘In July, 1819, one half of its enormous crown fell: the wound is plaistered up, the date of the misfortune marked on it, and as much care is taken of the venerable vegetable as will ensure it for at least another century’.

Graham commemorated the tree in an illustration that she made on the spot and which she had later engraved and published alongside her written description.

On a second trip to Brazil in 1824 – Graham had been asked to become governess to the eldest daughter of Emperor Dom Pedro I and Empress Maria Leopoldina of Brazil – Graham corresponded with botanist William Jackson Hooker at Kew Gardens in London, sending him dried plant specimens, seeds, and botanical drawings. In 1827 Hooker named a plant genus after her in recognition of the seeds she had collected in Chile. He later named the Escallonia Callcottiae (from Callcott, the name of her second husband) after her. See this image here.

Emily Elizabeth Ward

Emily Elizabeth Ward (née Swinburne, 1798-1882) grew up in Capheaton Hall, an English country house in the north of England. She learned drawing and painting from Irish painter William Mulready. In 1824 she married English diplomat Sir Henry George Ward. The couple sailed for Mexico in January 1825 after Ward had become chargé d’affaires in that country. They would stay in Mexico until 1827, meeting officials and inspecting mines around the country. Upon their return to England Henry Ward published his travel journal Mexico in 1827 (1828). Emily Ward provided the illustrations for the journal. These visuals reveal her keen interest in the natural world and her knowledge of Mexican plants and trees.

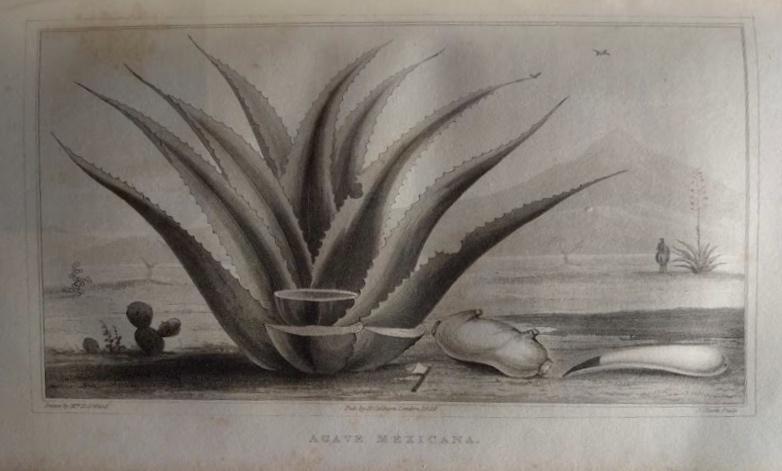

In this illustration Emily Ward depicts a plant called the Agave Americana, also known as maguey or American aloe. On the page facing the plate Henry Ward provides a written description of this plant and its usefulness, focusing specifically on its being the main ingredient for ‘the favourite beverage of the lower classes in the central part of the Table-land, a spirituous liquor called Octli, or Pulque’. According to Ward, ‘the natives ascribe to Pulque as many good qualities as whiskey is said to possess in Scotland’. This entry exemplifies the collaborative nature of Emily and George Ward’s botanical observations.

Natural History in Translation

Ward and Graham belonged to a select group of early nineteenth-century British women who travelled to Latin America and got to study the natural world with their own eyes. However, there were also women who contributed to natural history writing of the Americas without ever crossing the Atlantic. Helen Maria Williams (1759-1827) and Sara Coleridge (1802-1852), for example, translated influential travel narratives by European male travellers into English. In this period, translation was often seen as an inferior and derivative ‘feminine’ literary activity. But for Williams and Coleridge translation provided a way to access specialized botanical knowledge and participate in scientific discourse. In addition, their high-quality translations made the knowledge of Latin American flora and fauna contained in these works available in English for the first time.

Helen Maria Williams

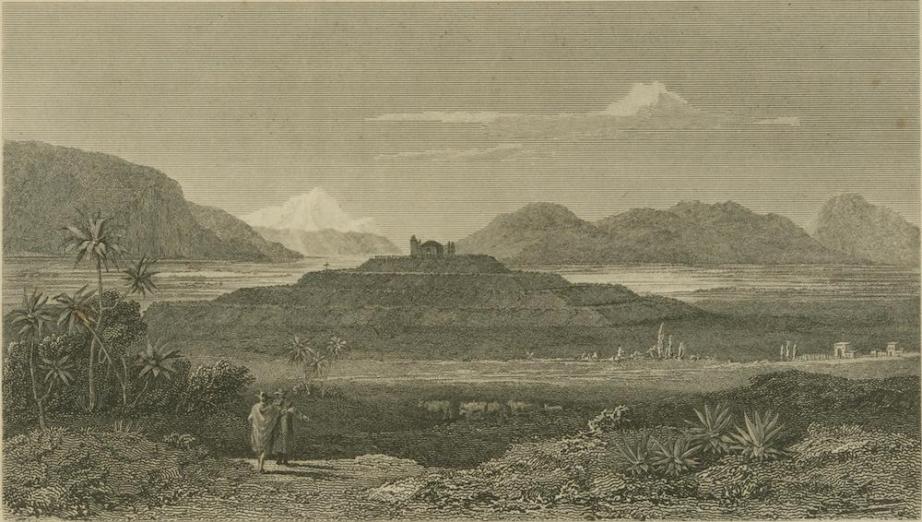

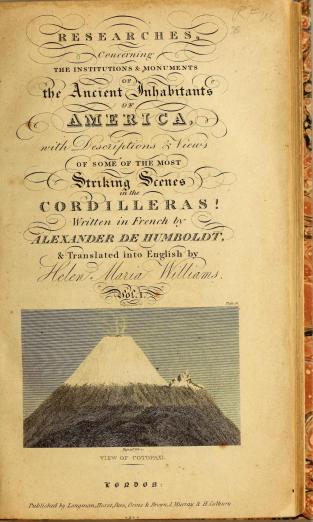

Helen Maria Williams (1759-1827) was a British writer. She went to France in 1790, where she would live for thirty years. In the years following the French Revolution she reported on current affairs in France in an eight-volume eyewitness account titled Letters from France (1790-96). In 1810 Williams started working on an English edition of two works on Spanish America by the famous Prussian explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. These works were published as Researches Concerning the Institutions and Monuments of the Ancient Inhabitants of America (1814) and the seven-volume Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent (1814-29). With her translations Williams aimed to make the texts particularly accessible to women and non-specialist audiences. See this image here.

This is the title page for the 1814 edition of Alexander von Humboldt’s Researches Concerning the Institutions and Monuments of the Ancient Inhabitants of America. Humboldt explored Spanish America with French botanist Aimé Bonpland between 1799 and 1804, collecting botanical and geological specimens, taking meteorological measurements, and climbing active volcanoes. Originally published in French, Williams provided the first English translation of this pioneering two-volume work. Although the title of the book suggests a focus on antiquities, Humboldt also included many observations on the flora and fauna of Mexico and Peru. Williams skilfully translated plant and animal names into English, demonstrating an expert understanding of the field. See this book here.

Sara Coleridge

Sara Coleridge (1802-1852) was a writer, editor, and translator. She was the daughter of the British Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Between 1818 and 1822, Sara Coleridge worked on an English translation of Martin Dobrizhoffer’s Historia de Abiponibus, originally published in Latin in 1785. Dobrizhoffer was a Jesuit from Graz, Styria (now Austria) who had spent eighteen years living among the indigenous Abipone and Guarani peoples in Paraguay. In 1822, Coleridge published the first English translation of this three-volume work under the title An Account of the Abipones, an equestrian people of Paraguay.

Sara Coleridge (1802-1852) was a writer, editor, and translator. She was the daughter of the British Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Between 1818 and 1822, Sara Coleridge worked on an English translation of Martin Dobrizhoffer’s Historia de Abiponibus, originally published in Latin in 1785. Dobrizhoffer was a Jesuit from Graz, Styria (now Austria) who had spent eighteen years living among the indigenous Abipone and Guarani peoples in Paraguay. In 1822, Coleridge published the first English translation of this three-volume work under the title An Account of the Abipones, an equestrian people of Paraguay.

Dobrizhoffer devoted a large part of volume 1 of An Account of the Abipones to describing the zoology and botany of Paraguay. Coleridge painstakingly and accurately translated numerous plant and animal names from the original Latin into English. See this book here.

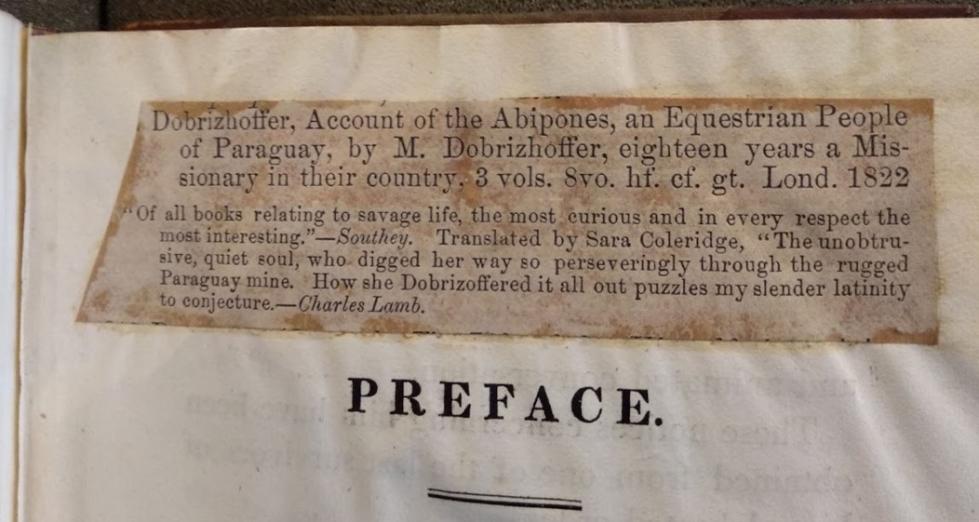

The JCB’s copy of the book contains a collection of ephemera that highlight Coleridge’s achievements as the translator of this work. A newspaper or journal fragment pasted into the book includes a quote by essayist Charles Lamb praising Coleridge’s translation skills:

‘Translated by Sara Coleridge, the unobtrusive, quiet soul, who digged her way so perseveringly through the rugged Paraguay mine. How she Dobrizoffered it all out puzzles my slender latinity to conjecture’.

An interleaved handwritten note includes a copied quote from Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who also speaks highly of her work. He writes that ‘my dear daughter’s translation of this book is, in my judgment, unsurpassed for pure mother-English, by anything I have read for a long time’.

Related Events

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

Credits

This exhibition was curated by Lilian Tabois (PhD candidate, English and Related Literature, University of York).