A healthy conversion: John Eliot, Robert Boyle, and the Algonquians

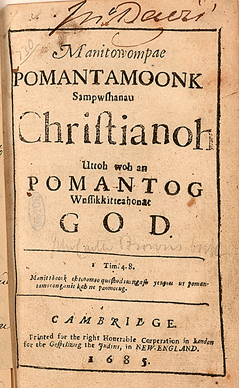

In 1685, John Eliot published an Algonquian translation of a popular English religious text, Lewis Bayly’s The Practice of Piety (London, 1613). This translation illuminates Eliot’s reliance upon medical knowledge to convert southern New England Algonquians. The Practice of Piety was a well-known, practical guide to Christian living; it was republished over seventy-five times in almost as many years. Bayly devotes a lengthy section to the “Practice of Piety in glorifying God in the time of Sickness, and when thou art called to die in the Lord” (p. 322). Containing prayers for healing, advice for settling one’s estate before death, and meditations for the sick, these chapters describe illness as a physical and spiritual condition. Patients “poisoned with the settling of Sin” (p. 336) were urged to recognize that their sickness was a “medicine,” sent by God to cure their souls (p. 347). Only through repentance were people healed of both soul and body.

In 1685, John Eliot published an Algonquian translation of a popular English religious text, Lewis Bayly’s The Practice of Piety (London, 1613). This translation illuminates Eliot’s reliance upon medical knowledge to convert southern New England Algonquians. The Practice of Piety was a well-known, practical guide to Christian living; it was republished over seventy-five times in almost as many years. Bayly devotes a lengthy section to the “Practice of Piety in glorifying God in the time of Sickness, and when thou art called to die in the Lord” (p. 322). Containing prayers for healing, advice for settling one’s estate before death, and meditations for the sick, these chapters describe illness as a physical and spiritual condition. Patients “poisoned with the settling of Sin” (p. 336) were urged to recognize that their sickness was a “medicine,” sent by God to cure their souls (p. 347). Only through repentance were people healed of both soul and body.

Eliot applies conceptions of illness as a spiritual affliction to his missionary work among the Algonquians. He hoped to replace the Algonquians’ “pawwawing” with Christian “medicine”–pious living that, he promised, would cure both their physical and spiritual illnesses. When I found Manitowompaeat the JCB, I realized just how extensive Eliot’s efforts to make “healthy” living part of his message were; his translation of spiritual-medical advice into Native languages supported his arguments against shamanism. In addition, the JCB’s copy of Manitowompae includes Eliot’s handwritten letter to Robert Boyle, the Royal Scientist, natural philosopher, and, from 1662 to 1689, governor of the Company for Propagation of the Gospel in New England. In the letter, Eliot writes that “our Indian work yet liveth,” telling Boyle that his Algonquian Bible and the Practice of Piety had just been published. Eliot’s letter and his translation of the Practice of Piety into Algonquian demonstrate the interplay between scientific networks and knowledge and colonists’ literary efforts to propagate the gospel in New England.

Kelly Wisecup, October 2008