Constellations: Reimagining Celestial Histories in the Early Americas

Here are the rules of the game: the library is the cosmos, its books are the stars, and we, as their readers, are celestial observers. At a distance, with instruments and conditions that are limited, our gazes travel, intermingle, pause, hesitate, and continue their trajectories, unraveling the unknown or perhaps encountering new outlines amongst the pages. The challenge is to place ourselves amongst a certain number of books, discover relationships, and create groups of objects – constellations – that speak to one another. These are the structural metaphors of the digital exhibition Constellations: Reimagining Celestial Histories in the Early Americas at the John Carter Brown Library, as we present to the public nearly 90 objects from its collections.

At first glance, the exhibition appears to have as its central theme the history of astronomy in the Americas. Or perhaps, even before that, is it not a history of the relationship of communities throughout the Americas with the heavens? Or better still, a history of the American skies? Choosing any of these as a central question – among many other possibilities – would imply distinct and not necessarily compatible propositions. Accepting incompatibilities, failing to resolve these tensions, and refusing to offer a particular response to a single dominant query is the vision that inspires Constellations and the histories that are recounted through it.

Our constellations are unexpected groupings, unstable and changing objects that testify to the distinct meanings that the heavens revealed for the Americas, from the Americas, within the Americas. We invite you to contemplate these skies with us.

To enjoy a digital immersive experience, and to see the videos and events associated with this exhibition, make sure to visit our special landing page!

Learning to Navigate the Skies

Learning to read the skies for knowing one's place on the earth or in the Universe was an integral part of the culture of mariners who crossed the Atlantic back and forth, of writers who wanted to make sense of the relation between the Old and the New World, and of educational curricula of institutions ranging from grammar schools to universities, religious colleges, and military academies. The materials displayed in this constellation give witness to the variety of ways in which astronomical knowledge was taught and learned: navigational manuals, textbooks, treatises, dissertations, maps, or even prefatory material to books on history. Some of them were published in Europe, but found their way to the early Americas, while others were locally written, or built upon the lived experiences of their authors in the New World.

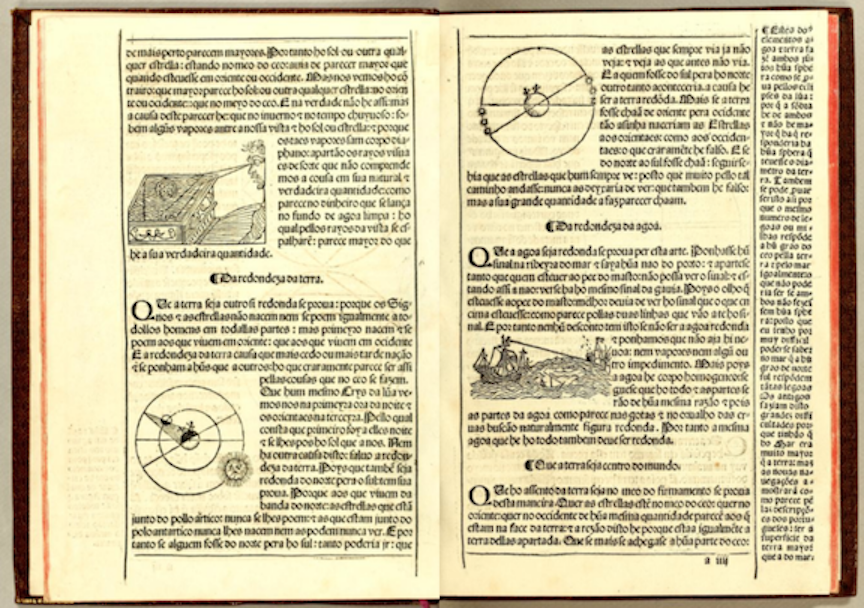

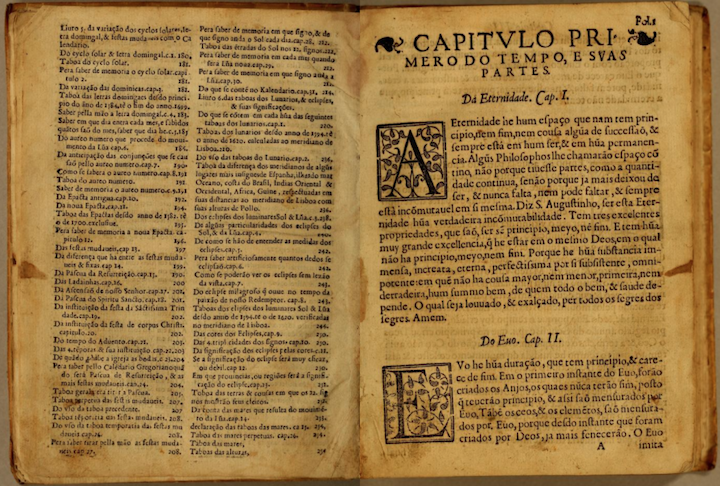

Sacrobosco's Sphere – in Portuguese

The Tratado da sphera is the first Portuguese translation of Johannes de Sacrobosco's thirteenth-century didactic treatise of the same name, and arguably the most successful introduction to astronomy of the first two centuries of printing. Pedro Nunes's translation comes with profuse commentary and includes other astronomical texts, besides two short treatises by Nunes himself on the applications of astronomy to oceanic navigation.

First things first

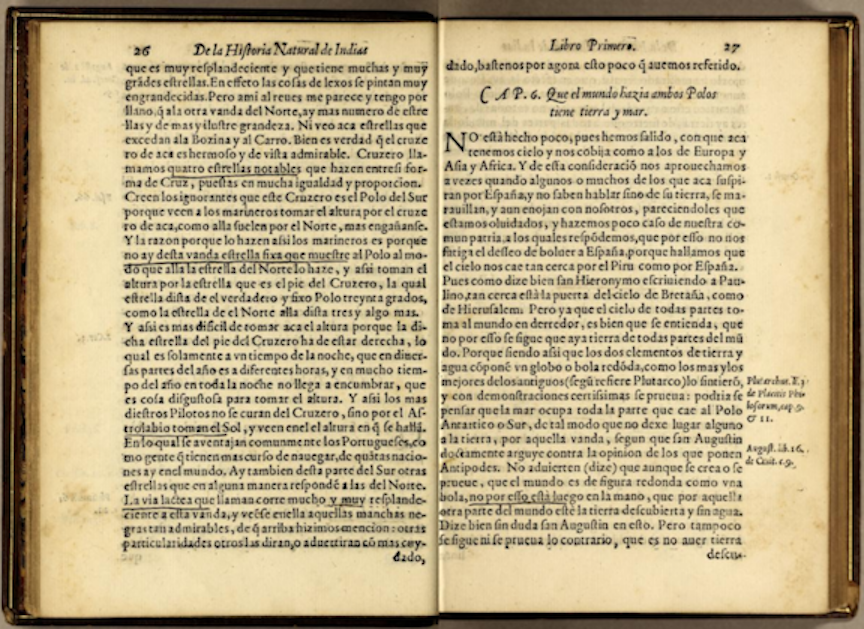

Digital version here.

One of the most influential books on the Americas ever written, Jesuit José de Acosta's Historia natural y moral de las Indias is, at the same time, chronicle, blueprint for evangelization, natural history treatise, political statement, and a traditional cosmographical work. Displayed here is a page from the book's introduction, revisiting the usual themes of treatises on the sphere before progressively coming down to earth – down to the most minute details of the natural and social worlds of the Andes.

Apian's paper instruments travel to the Americas

Drawing from the didactic tradition of Sacrobosco's De sphaera, and making use of the full range of possibilities offered by the printing press, Apian produced one of the most influential sixteenth-century introductions to astronomy and navigation. One part textbook, another manual, and including a set of "paper instruments," Apian's work was translated from Latin into at least fourteen languages before the end of the century, circulating in many relatively inexpensive editions like this one. In the early Americas, Apian's cosmographical texts were frequently read in portable and affordable formats, such as the in-quarto Spanish edition displayed here.

A little book for young students

for the use of children. Digital version here.

Barely one year after the publication of An astronomical and geographical catechism, a book that was directed specifically to children, this copy came into the possession of one Cornelia Arnold, as can be seen in the image. Cornelia, 11-years old, was likely the daughter of a wealthy Providence merchant, while the book's author was a schoolmaster in nearby Boston. With very small physical dimensions, and written in the form of short questions and answers – that were meant to be memorized by heart – the book is a poignant testimony of the place of astronomy in the education of children, particularly girls, in the early United States.

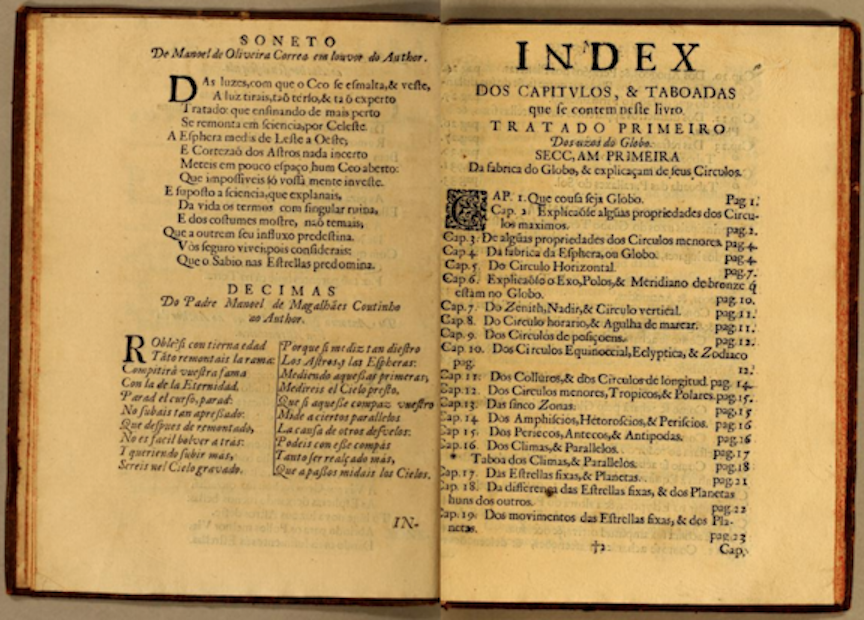

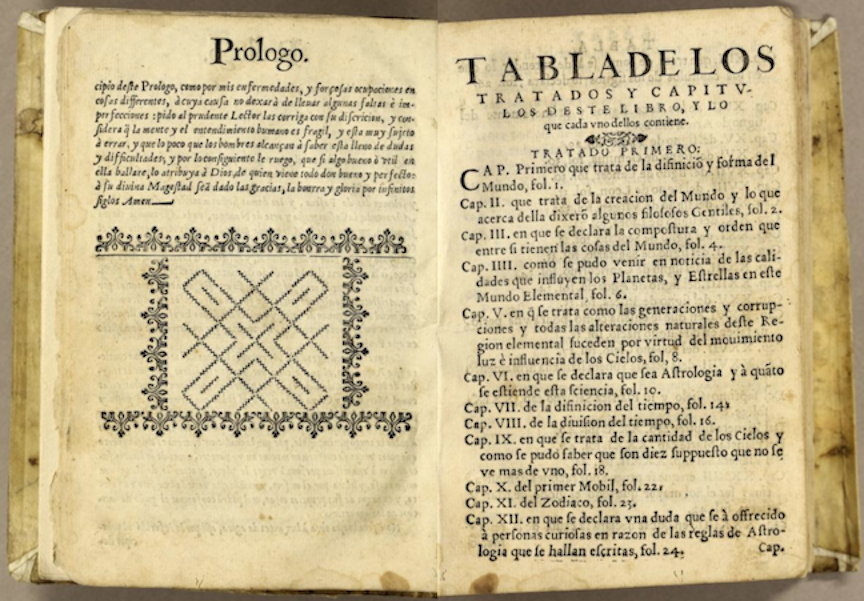

The persistence of the sphere

Carvalho da Costa was a Portuguese priest and author of many books on astronomy, geography, history, genealogy, and antiquities. A contemporary also credits him with publishing several astrological prognostics – or portents – under pseudonym. Published in the late seventeenth century, this particular book, an introduction to astronomy, is arranged according to a very traditional scheme reminiscent of Sacrobosco and others' "treatises on the sphere," testifying to the longevity of this genre in didactic settings in Europe and across the Americas.

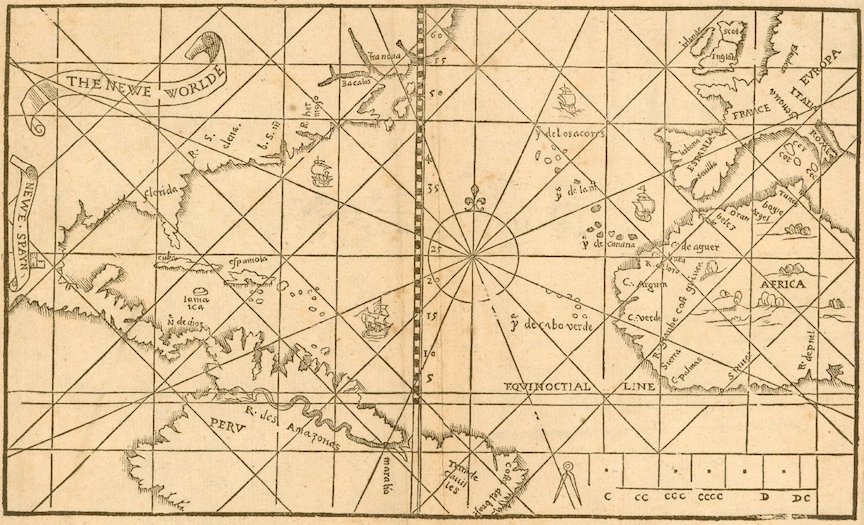

A sixteenth-century international best seller in navigational astronomy

Cortés's Breve compendio de la sphera was one of the most successful practical manuals of navigation published in the sixteenth century. The author belonged to the first generation of Spanish theoretical cosmographers to win the upper hand over practical pilots – much to the latters' chagrin. Nevertheless, the instructions for oceanic navigation contained in Cortés's text were quite useful, with plenty of practical astronomical operational sequences. The book captured the attention of British mariners soon after publication, and went through seven English editions – like this one – in the sixteenth century alone.

How to sail to the Equator?

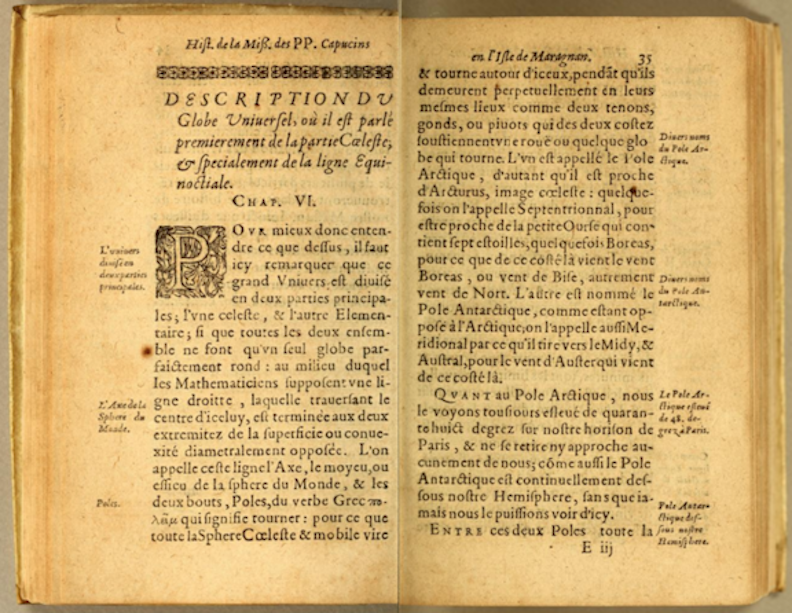

capucins en l'isle de Maragnan. Digital version here.

The Capuchin missionary d'Abbeville was a member of the short-lived French colonial enterprise in Northern Brazil, "Equinoctial France," which lasted only three years (1612-15). The Histoire was published while the colony still seemed viable. Mostly a chronicle of the missionaries' deeds, in the spirit of several other narratives of "spiritual conquest," it also includes preliminary cosmographical material, such as this description where d'Abbeville didactically discusses the nature of the Equator and how the French sailed there.

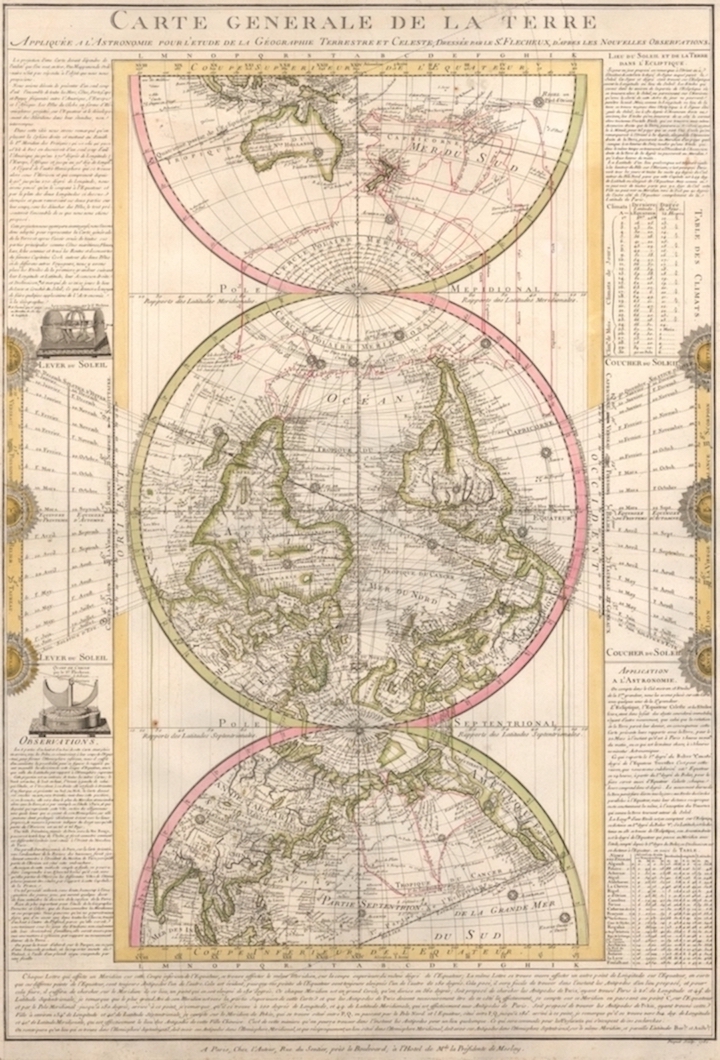

Imaging the world from the sky with astronomical instruments

a l'astronomie. Digital version here.

Flécheux’s map of the world conveys the theoretical, technical and epistemic ideals of fully describing the world by correlating the skies and the earth. This object was made for didactic purposes and the promotion of the author's inventions. The two hemispheres from a polar view, as presented here, was an innovation explained in marginal text. This pedagogic visualization was also conceived so that viewers imagined the Earth from above the celestial spheres. The depiction of the Americas includes surveys informed by exploration voyages and contemporary exchanges between colonial informants and scientific centers of information gathering. The map is framed by astronomical instruments made by Flécheux and explained in independent supplements, also held in the JCB collections.

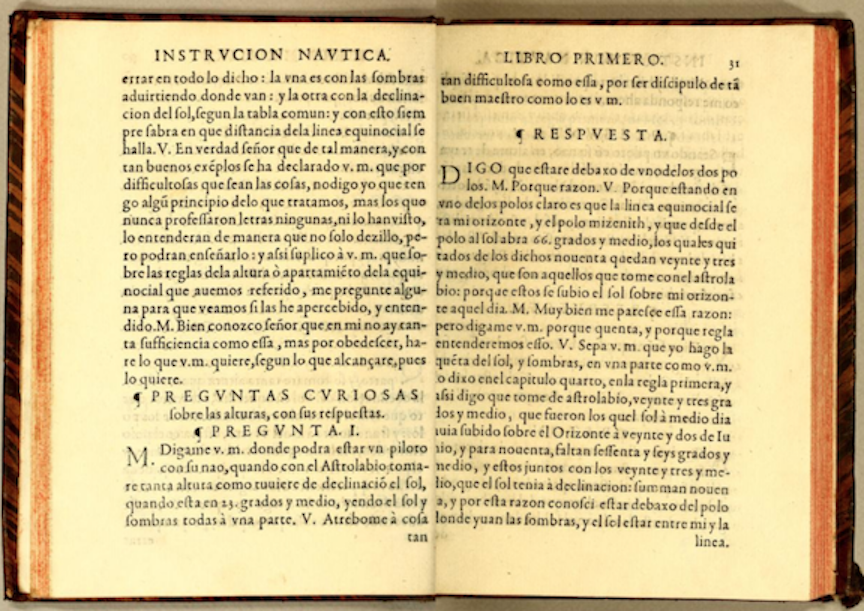

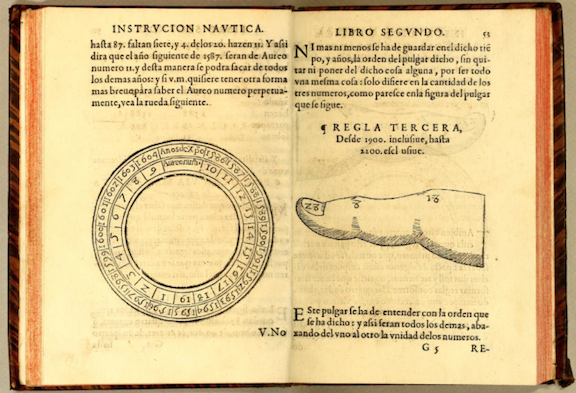

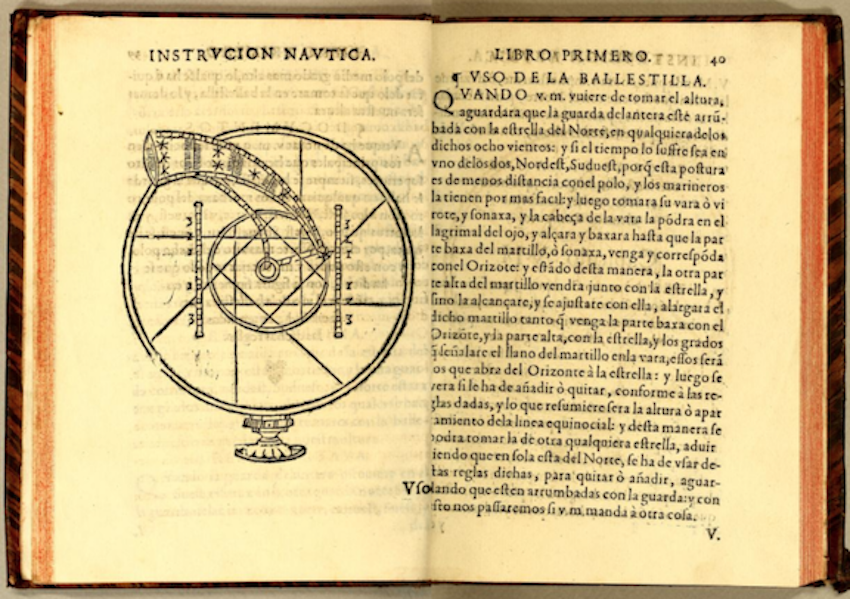

Navigational instructions for early audiences in New Spain

García de Palacio's Instrucion nauthica was the first book on practical navigation printed in the Americas. The author, a Spanish captain, challenged Francis Drake along the coasts of America, and was later named rector of the Real y Pontificia Universidad de México. Seafaring theory and practice, including naval construction, is conveyed through a dialogue between two Spaniards, Montañes and Viscayno, who discuss how to use astronomical instruments and read celestial signs at sea. The knowledge contained in this work is directed toward colonial elites who were regularly moving between New Spain and other Spanish vice-royalties in the Americas.

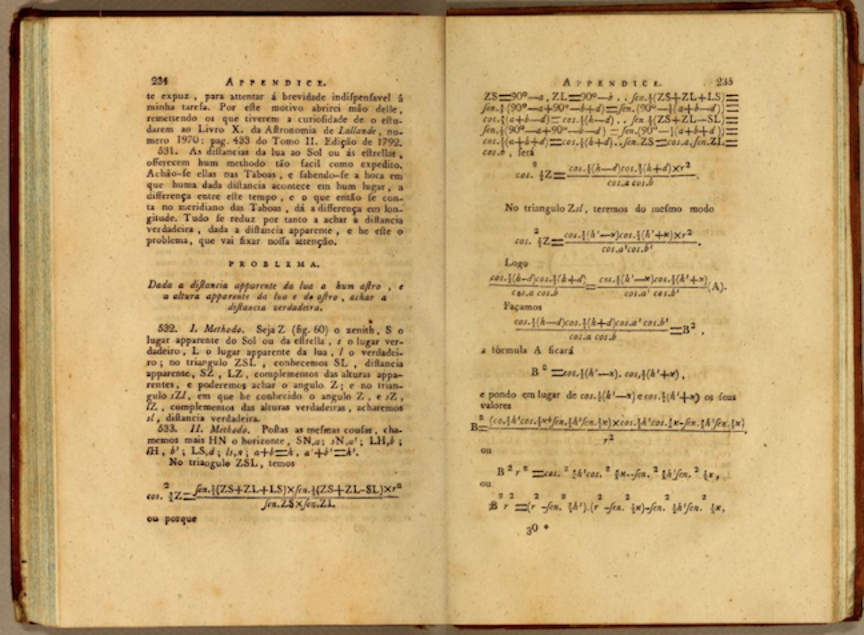

The first textbook of astronomy published in Brazil

astronomia para uso dos alumnos da Academia Real

Militar. Digital version here.

Astronomy was considered integral to the training of several grades of military officers in army and naval academies across Europe and the Americas. This is the first astronomy textbook written and printed in colonial Brazil, shortly after the arrival of the printing press in Rio de Janeiro in 1808, and it was meant to be used at the newly established military academy. It emphasizes learning through mathematical exercises, just as in the author's French and English sources.

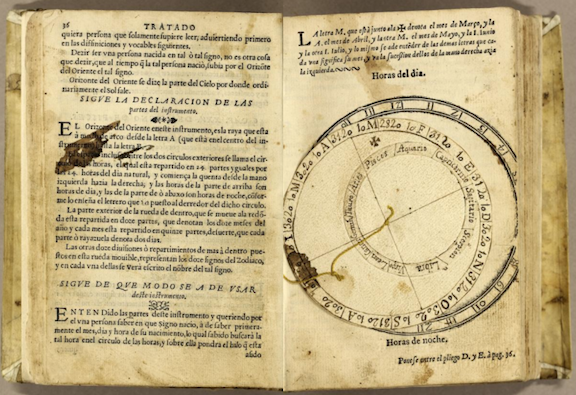

Practical advices for celestial observers in New Spain

natural desta Nueua Espana. Digital version here.

Along with García de Palacio’s navigational instructions, this work was one of the earliest books with practical advice for celestial observation printed in the Americas. Dedicated to the Viceroy of New Spain, it offers a compendium of astrological and astronomical knowledge in Spanish. Martinez challenges a European tradition in light of his American observations.

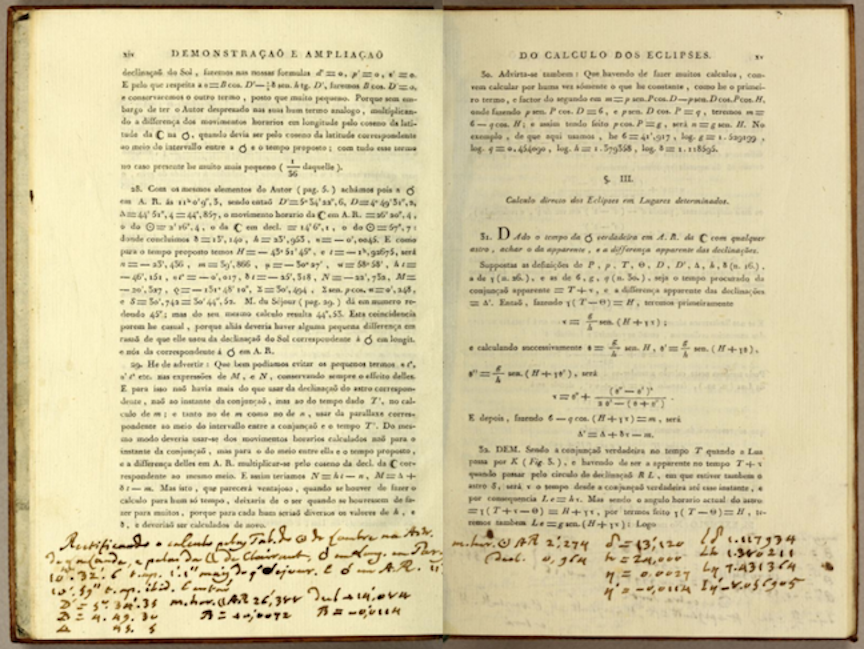

An astronomer and teacher trained in eighteenth-century Brazil

do calculo dos eclipses. Digital version here.

Monteiro da Rocha (1734-1819) was a former Jesuit priest who was trained in astronomy in Salvador da Bahia, where he wrote the oldest extant Newtonian astronomical work from colonial Brazil. After relocating to Portugal, he was one of the main architects of the reform of the University of Coimbra, creating its mathematics degree. Many Brazilian-born students went to Coimbra around the turn of the nineteenth century to study mathematics and astronomy under Monteiro da Rocha, learning calculational techniques similar to those developed in this dissertation.

Someone in New Spain studies astronomical navigation

Digital version here.

This heavily annotated copy of Zamorano's practical treatise on navigation is a testimony to the didactic value of his work for individuals across the Spanish empire: the book was zealously studied. Zamorano was the cosmographer of the Casa de la Contratación in Seville, the all-powerful institution that managed Spanish transoceanic trade. Several of these annotations, such as the ones displayed in this image, were made by a previous owner of the book, living in New Spain.

Prognostications in Print

The relationship between astronomical phenomena and time-reckoning is so prominent that it is almost unnecessary to reiterate it. Most calendars in the world are based on the periodic motions of the sun, the moon, or both; the date of religious festivals, particularly Christian ones, is as a rule connected to some celestial configuration; seasons and tides, the time to seed or to harvest, days of market or court, the time to sleep or to wake up -- astronomical rhythms invade human life in every scale, from the most minute, intimate affairs all the way up to momentous civic, religious, and political events. The desire to predict the future, to tame time, pervaded societies across the early Americas: from knowing the date of next year's Easter day to the coming solar eclipse, through the date of a notable planetary conjunction believed to interfere in human affairs or the birthday of an influential individual, this constellation suggests the many ways through which the heavens made the future of communities in the early Americas.

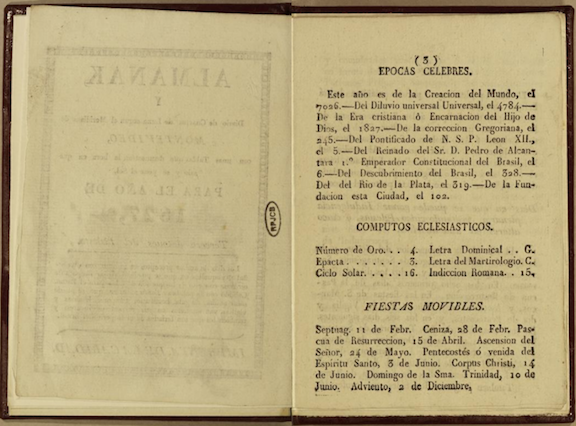

Time and nation-building in Montevideo

This "almanak" from the Río de la Plata region shows a complex interplay of political allegiances, produced as it was in the early national period when Montevideo was briefly part of the Brazilian empire. In the summary of "famous epochs," one finds references to the timing of Biblical and religious events, the foundation of the city by the Spanish, and the independence of Brazil from Portugal, among others.

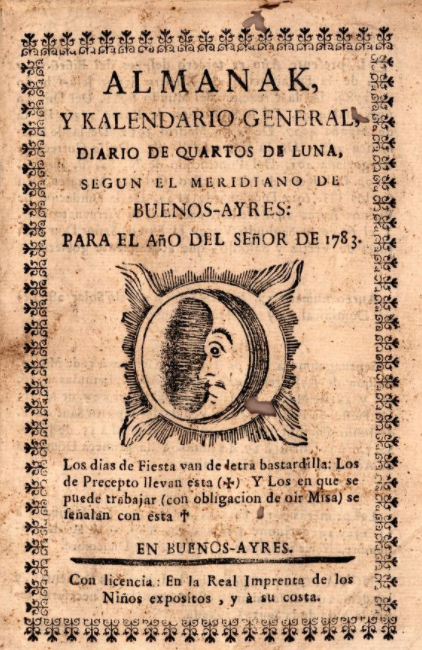

An almanac from late-colonial Buenos Aires

Digital version here.

Almanacs are the most widespread print genre related to astronomy. Across the Americas, wherever there was a printing house, chances are good that at least one almanac was published on a yearly basis – for many decades. Even though they are seemingly universal as a genre, almanacs are also a profoundly local business, tied to specific markets and political conditions, as is the case with this example from late-colonial Buenos Aires.

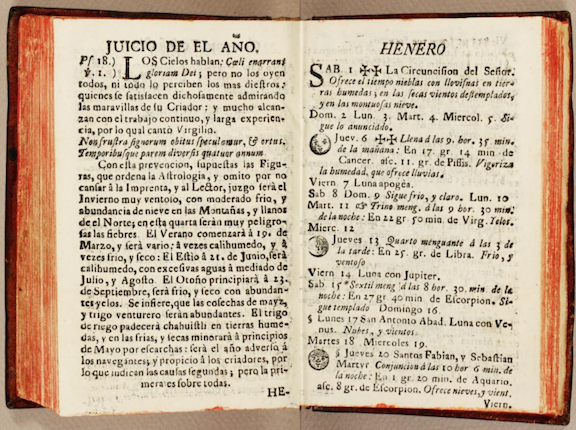

Reportorios: Inquiring into the nature of time

Digital version here.

Not to be confused with almanacs, "reportorios" were a specific genre that met with considerable success in Spain, Portugal, and their American possessions during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. They drew from astronomy, philosophy, calendrics, and, above all, astrology in order to explain the mysteries of time. André do Avelar's book was banned by the Inquisition, but this did not prevent it from being one of the three books owned by an apothecary who died in 1633 in the village of São Paulo, Brazil.

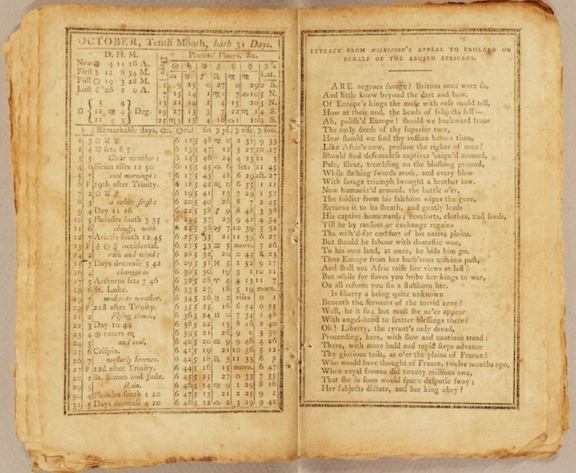

A time for freedom

Benjamin Banneker is the only known African-American author of almanacs in British North America, and he was a successful one at that. The grandson of a formerly enslaved African man and a free African-American woman, Banneker was able to place his publications in five different cities – including Philadelphia, origin of this copy – during a highly competitive period for almanacs in the late-colonial and early-republican print market. His almanacs were overtly political interventions that interspersed the usual time tables with strong antislavery quotations.

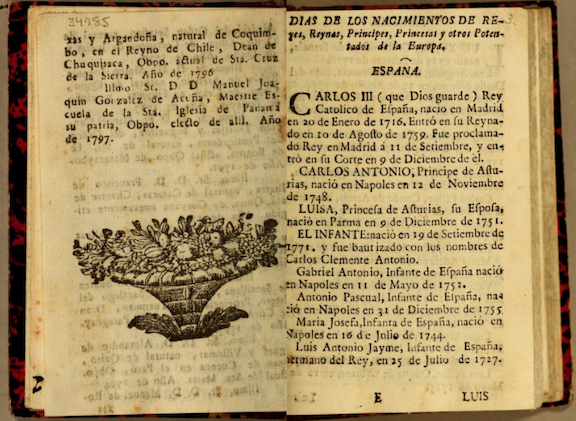

Almanacs and health in the Andean Enlightenment

Digital version here.

Cosme Bueno was trained at the University of San Marcos as a physician, and later became chair of mathematics and Cosmógrafo Mayor of the Vice-Royalty. In keeping with the requirements of his cosmographical office, which had been in existence nearly without interruption since the previous century, he oversaw the publication of the official almanac. Besides the traditional subject matter, such as can be seen to the right of this image (dates of birth of members of the royal family, for civic and astrological puroposes alike), Bueno appended to the almanacs medical and natural historical dissertations and health advice, which form a lasting testimony to the intellectual breadth of the Andean Enlightenment.

A woman author of Ephemerides in New Spain

Ephemeris calculada al Meridiano de México....Digital version here.

María de Gonzaga’s work complies with every convention of the ephemerides genre: an emblematic title page, author’s introduction, and tables with predictions. Past prognostics help establish patterns for the future. The copy in the JCB (the only known extant exemplar) is bound with 8 other lunaries, calendars, almanacs and ephemerides printed in Mexico City, Puebla, and Spain. These books of time prognostication were international genres and their publication served to create local audiences.

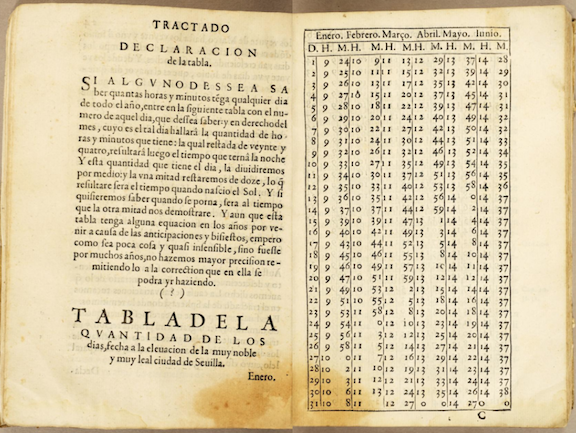

Prediction and prognostication

Digital version here.

Although reportorios shared some of the same functions of the simpler and much less expensive almanacs, they were lengthier treatises that aspired to present a more general description of the workings of time: either uniformly repetitive time, such as this table that brings the length of daylight experienced at the latitude of Seville on any given day, or the time of specific events, based on astrological prognostics. Chaves's work was broadly read across Spanish America.

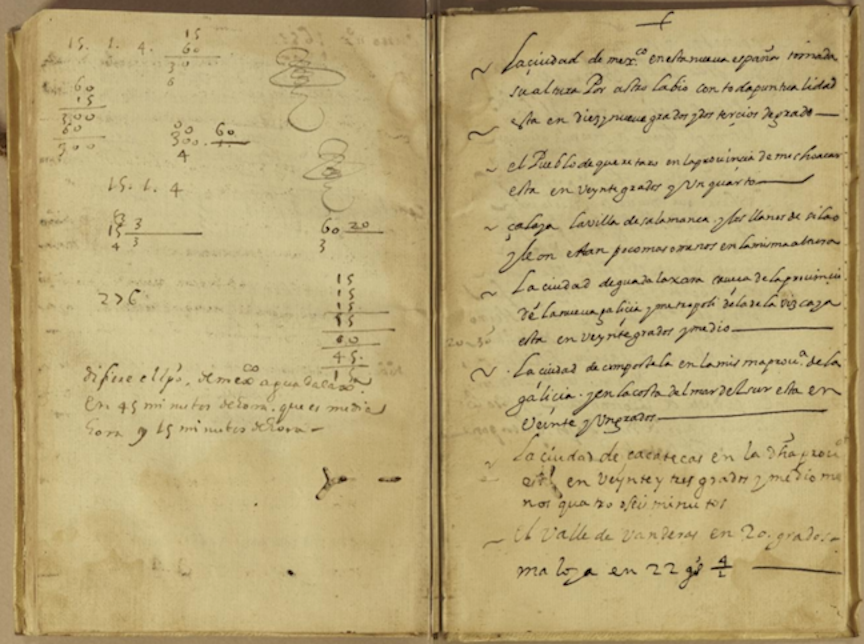

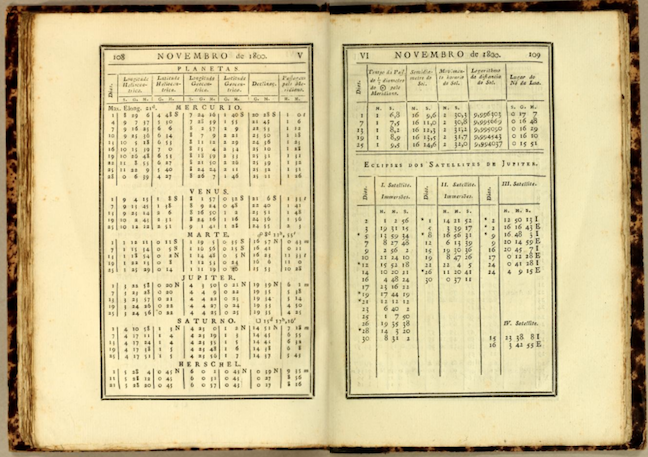

From time difference to geographical longitudes

Predicting the precise celestial coordinates of planets for each day of a coming year was a way of controlling space through controlling time: by knowing such coordinates – for instance, as they would be measured by an observer in Lisbon, as was the case in this official Portuguese ephemerides book – one could aspire to making precise longitudinal determinations for any other place in the global Portuguese empire.

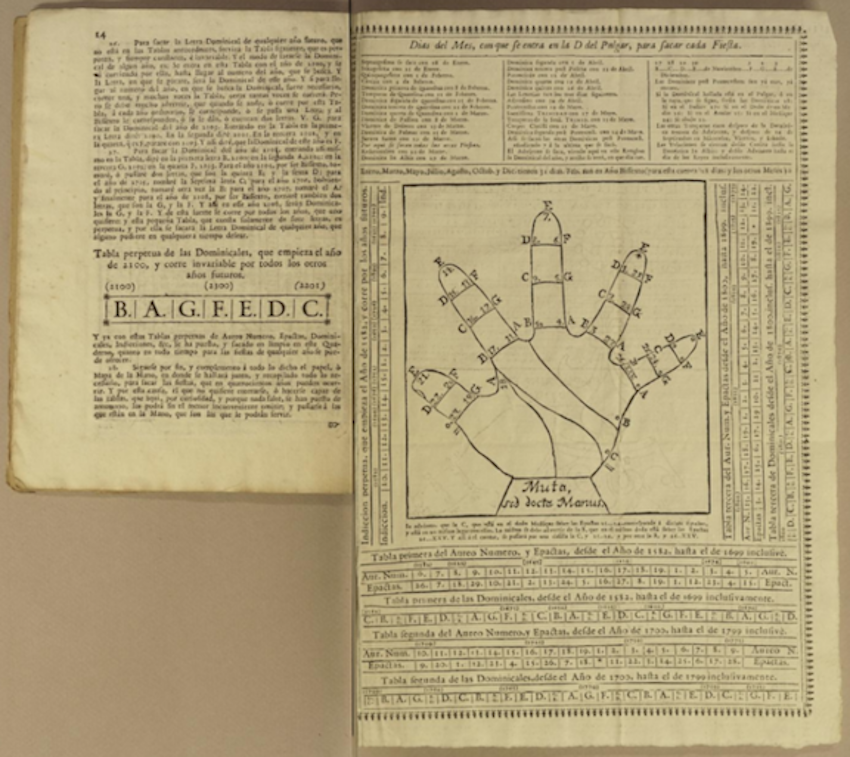

Teaching bodily gestures for calculating time in New Spain

Knowledge of the moon cycle is of paramount importance for the establishment of the liturgical calendar and navigation. Bodily techniques, such as the one described in this thumb diagram by Diego García de Palacio, were taught for the computation of Easter and the prediction of tides at sea.

Affordable instruments for casting horoscopes in the Americas

Astrology plays an important part in the literary culture of time-predicting that was present in the early Americas. In his Reportorio, Enrico Martinez explains how to calculate a person’s horoscope with instructions that require basic literacy and a paper instrument. The volvelle in this copy still moves and maintains its original thread as well.

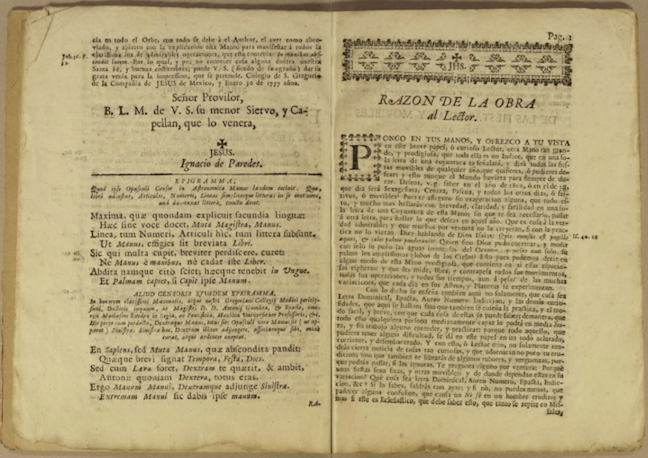

Reckoning time with one's hand

Astronomica, y harmoniosa mano. Digital version here.

Almanacs brought information about all the relevant events in the year to follow: religious and liturgical dates of significance, notable astronomical configurations, even meteorological forecasts. But early modern authors devised other ingenious schemes to help others keep track of time as well, advertising them as perpetual alternatives to some of the functions served by almanacs. This book by a Mexican priest offered detailed instruction for how to establish the date of any moveable Catholic feast through a process of finger-reckoning.

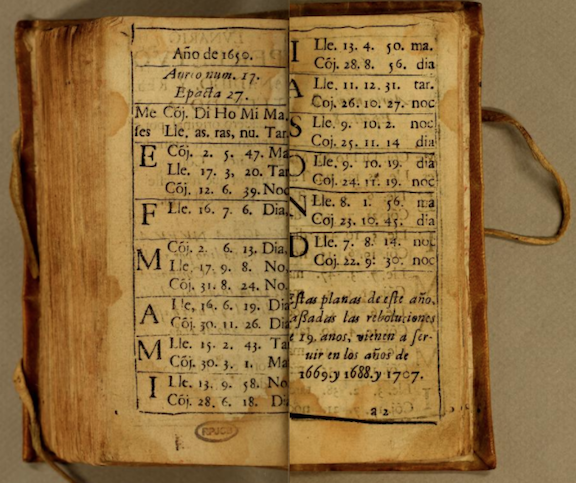

Lunar cycles, liturgical years

Quirós (1590-1645) was the second Cosmógrafo Mayor of the Vice-Royalty of Peru. Besides granting licenses to ship pilots and overseeing engineering projects, he was expected to produce astronomical tables such as this perpetual lunar calendar calculated for the meridian of Lima. The moon cycle determined the liturgical calendar and was essential knowledge for priests. The original owner of this copy had it bound together with a catechism in Quechua and Spanish published the same year.

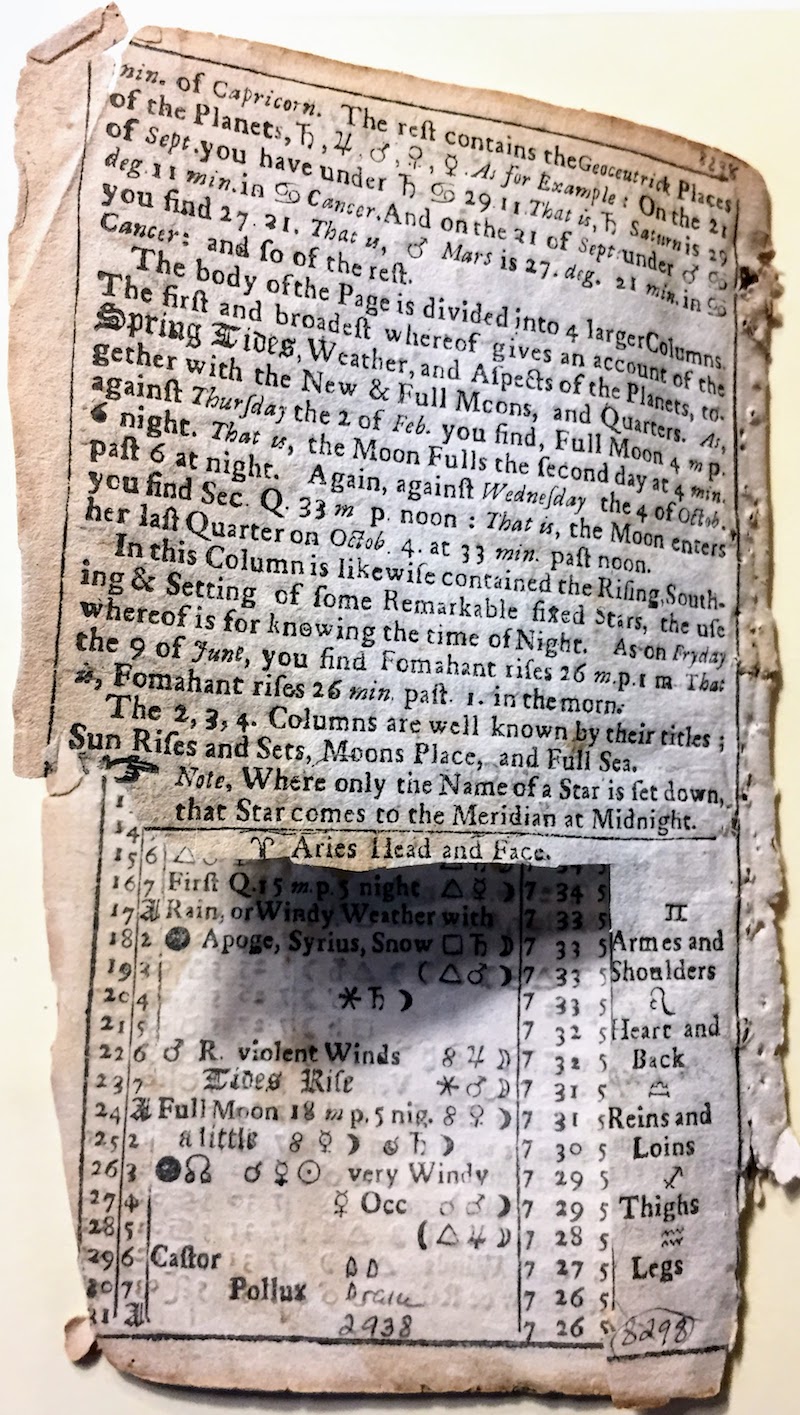

Not meant to lay quietly on a bookshelf

motions, Aspects and Eclipses, &c.

Catalogued here.

Across the early Americas, almanacs were not only owned, but used – and heavily so. Almanac makers partnered with publishers, who for decades were able to run very successful businesses since a new almanac had to be brought every year. The exemplars here come from the Boston printing house of Bartholomew Green, who published Robie's almanacs for some twenty years. They present several kinds of information for the year to come, often associating events with astronomical configurations: holy-days, markets, court sessions, seasons, and the weather forecast. Owners used almanacs to take note and keep track of life events, and occasionally cut out illustrations they found particularly useful, such as the Zodiac man here.

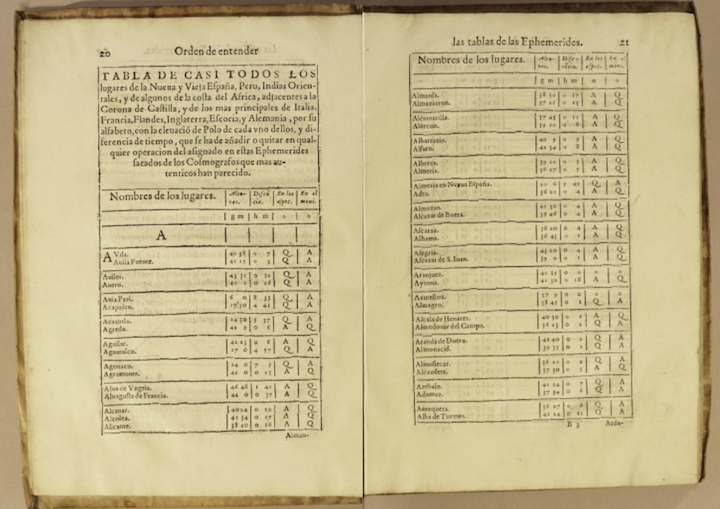

A Timetable for the Spanish empire

This elegant book, a recent acquisition for the JCB, was printed by the stationer responsible for the first edition of Cervantes' Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha, and it contains all the graphical conventions associated with predictions of astronomical events, including astrological charts dating equinoxes and solstices, lunar and solar eclipse diagrams, and elaborate tables. The book's innovation lies in its inclusion of the latitude and, more importantly, the longitude of several American cities. Here the reader would find time difference across the Americas, as calculated based on the meridian of Madrid.

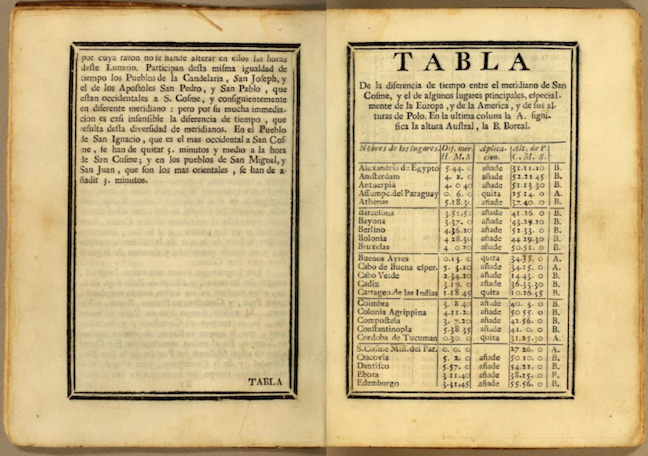

Time and space begin in Paraguay

Although printed in Lisbon, this Lunario was written in its entirety in the Jesuit reduction of San Cosme y San Damián, in present-day Paraguay, where the author, a native of neighboring Santa Fé, spent several decades. Besides a hundred-year long lunar calendar and eclipse canon, the book presented the time difference between the tiny locality of San Cosme and several large cities around the world, effectively asserting the meridian of San Cosme as the origin of longitudes.

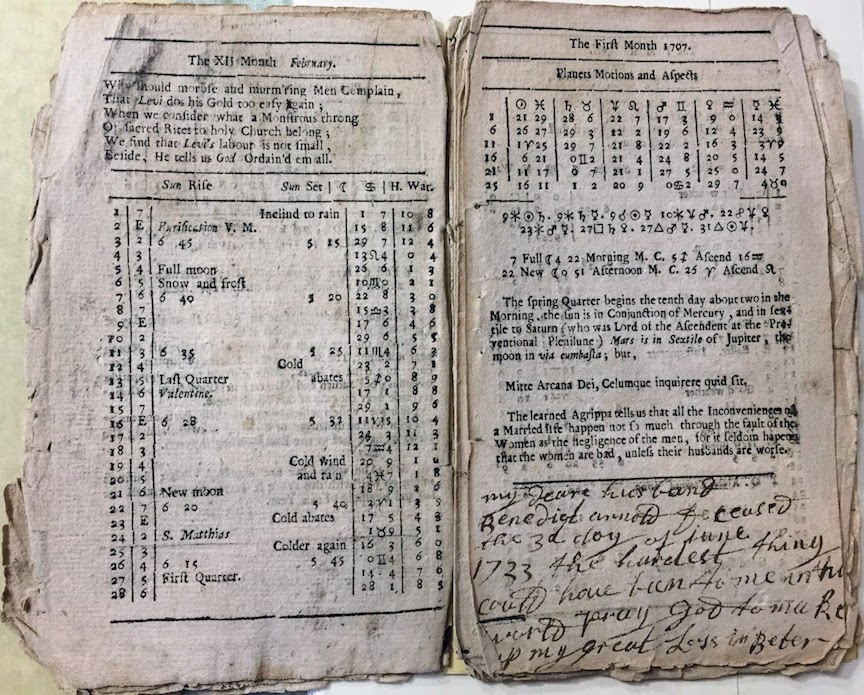

Keeping track of intimate life events

Almanacs were among the most widespread print products in British North America and the early republican United States. Working across class, gender, and racial lines, they were read, annotated, and passed among several hands each year, prior to the publication of new editions that would start the process all over again. Readers occasionally continued to take notes on important events in their lives decades after the information in the almanac had expired. This 1706 exemplar from Philadelphia contains a poignant annotation made by a woman in 1733, noting the passing of her husband.

Instrumental Pursuits

Instruments for star gazing aroused awe, desire, curiosity, obsession, distrust and speculation. These fragile objects, represented in books, engaged the body, reason, memory and imagination; and they were also related with the creation of authority and strategies of legitimation in local and global contexts. Instruments were conditioned by local resources and practices, and colonial asymmetries. Astronomical practitioners living in the Americas had very conflicting attitudes towards instruments for navigation, timekeeping, geography, earthquake and meteorological predictions, as these objects were commonly linked to personal or national pride. This is not a story of the reception of European technology in the Americas, but a collage of conflicting attitudes toward instruments as found in periodicals, pamphlets, images and maps.

“We write so that you might deign to appease our anxiety…”

literatura, y noticias públicas. Digital version here.

A letter by a reader of the erudite periodical Mercurio peruano, published in Lima, exhorts the publisher to satisfy its suscribers' "innate curiosity and natural propension to knowledge" and provide them with annual lunar tables, a dissertation about the periodicity of comets, and a table of eclipse predictions. This manifest desire to possess instruments for astronomical prognostics, read alongside historical and economic essays, was integral to erudite Peruvian sociability in the late-eighteenth century.

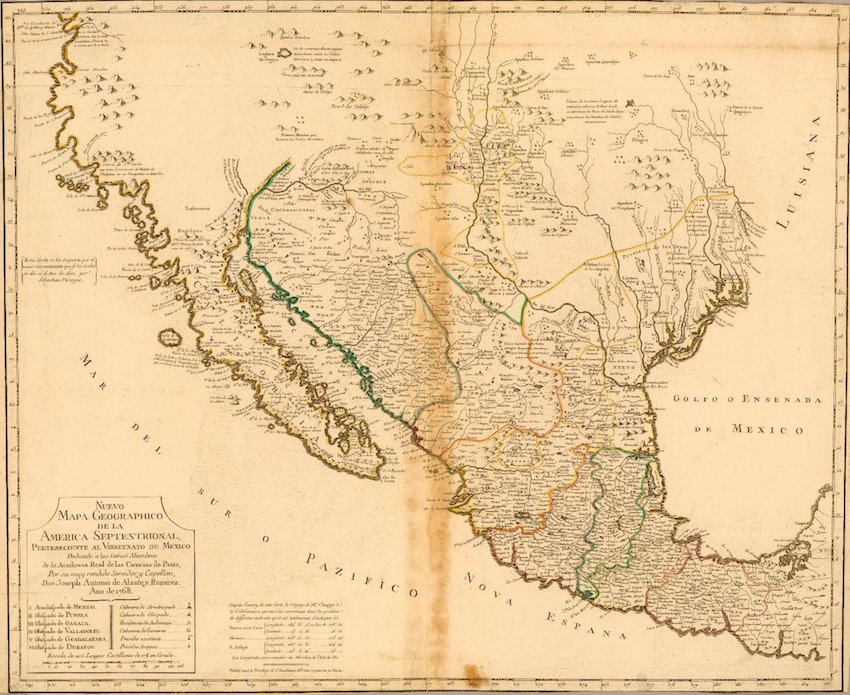

A map of Mexico as an instrument of legitimation

de la America septentrional. Digital version here.

The source of this printed map is a manuscript prepared by Mexican polymath José Antonio Alzate in Mexico City, sent to the Parisian Académie des Sciences in 1768, and edited yet again in Paris the early 1770s. Though the French edition was intended to promote l’Académie des Sciences, this map served Alzate as an instrument to legitimate his astronomical practices.

Diligence and anxiety for American science

With this pamphlet, José Antonio Alzate aimed to correct the meridian of Mexico City through the observation of a lunar eclipse. He circulated this work locally and, seeking foreign recognition, also sent it to the Académie des Sciences in Paris along with a chest of natural specimens. Although Alzate was proud of his experimental protocols, he lamented not possessing European instruments, which he deemed more authoritative than his own. Despite this overt technological anxiety, in this work – as in many others – Alzate proclaimed the dignity of intellectual and scientific endeavors taking place on American soil.

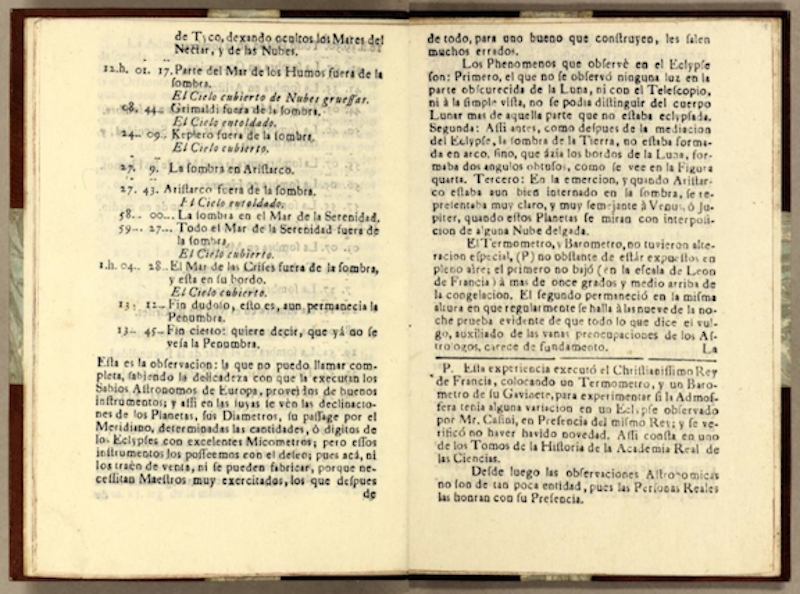

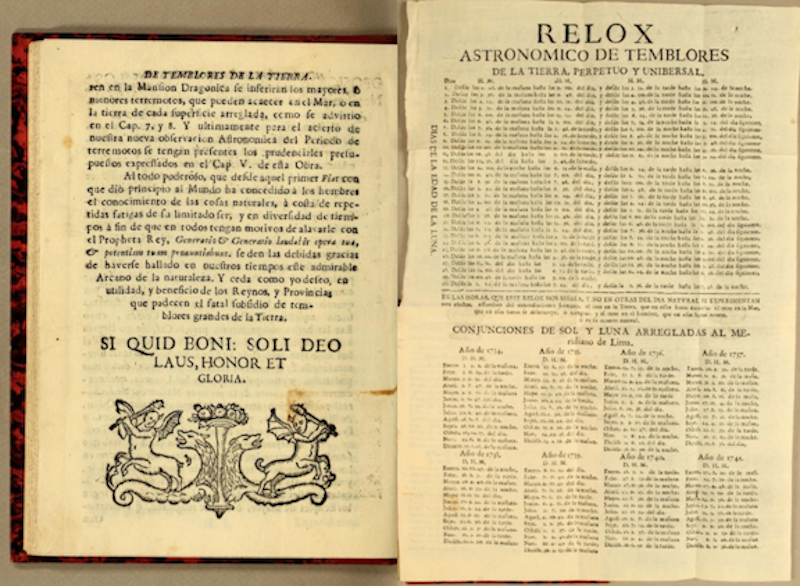

An astronomical clock for predicting earthquakes in Peru, Chile and Guatemala

tragico de los temblores grandes de la tierra. Digital version here.

The Nueva obseruacion astronomica promotes an astronomical clock for the prediction of earthquakes in Peru, Chile and Guatemala. The author – who was also the inventor of this instrument – was a Spanish military officer, tax collector in Lima, and substitute chair of mathematics at the University of San Marcos, who had experienced the catastrophes produced by these events in Peru. With this instrument he claims to have uncovered a hitherto unknown connection between the time and location of earthquakes, and the position of the moon and the stars.

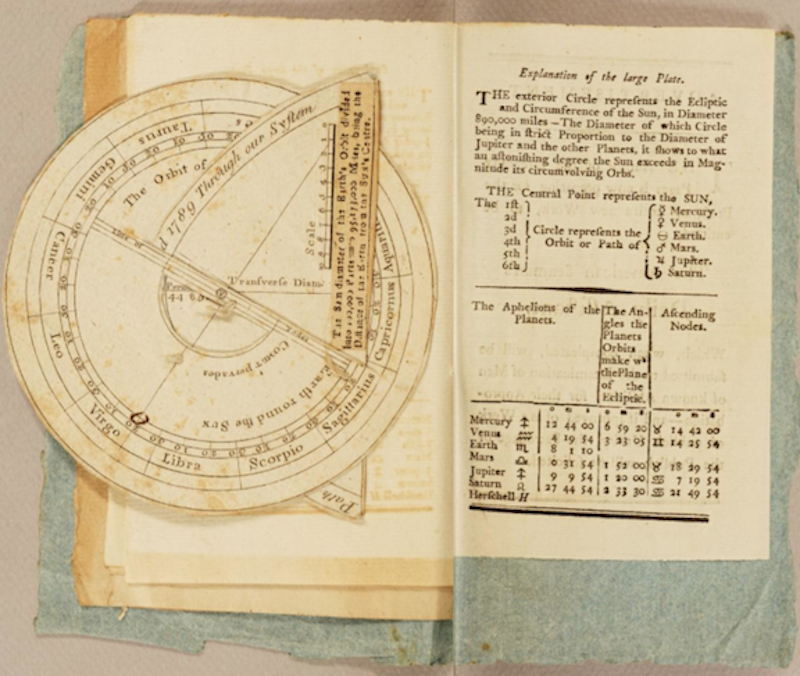

Demand for paper instruments in New England

system and of comets in general. Digital version here.

This beautiful paper instrument, similar to a volvelle, is elegantly displayed in a work on comets for a New England audience. The diagram represents a world system with the Sun at its center and is supposed to help measure the distance between the comet, the Sun, and the Earth. This publication attests to the appeal and commercial value of instrument making in late-eighteenth-century New England.

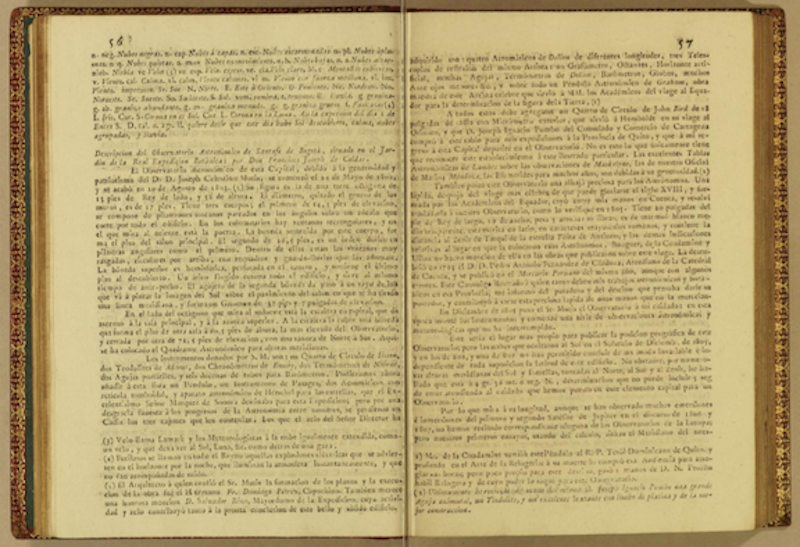

Promoting the observatory of Santa Fé de Bogotá

de Granada. Digital version here.

Late-eighteenth-century erudite periodicals were instrumental in displaying what was considered to be progress in the sciences on a national scale. In the first scientific journal of New Granada, Francisco José de Caldas proudly described the inventory of instruments held in the newly founded observatory of Santa Fé de Bogotá. However, he also lamented the impossibility of providing the longitude of the observatory because of perpetually cloudy weather.

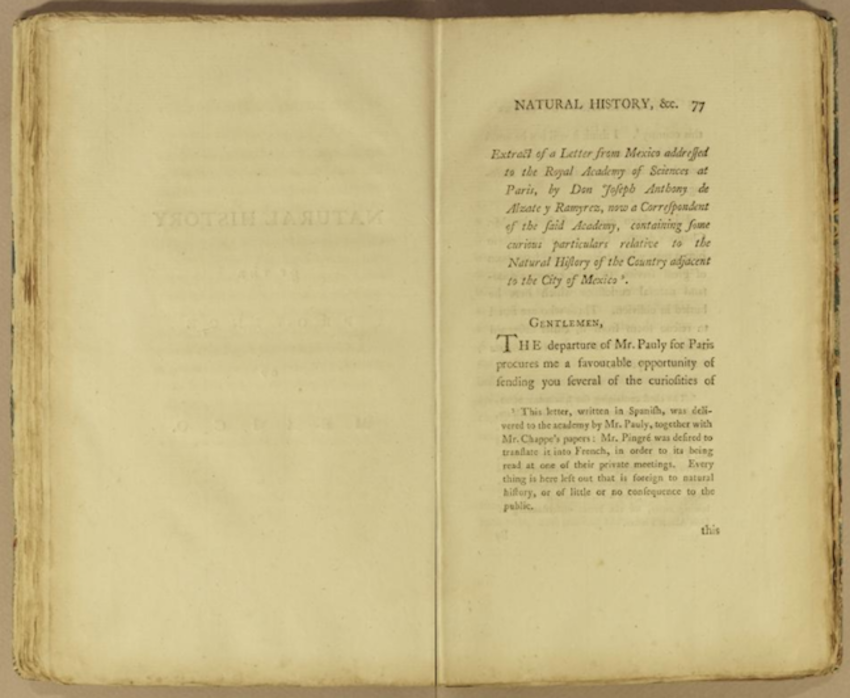

Exchanging knowledge for instruments and credit

the transit of Venus. Digital version here.

Chappe d’Auteroche’s passage through New Spain to observe the transit of Venus in California was a display of astronomical apparel. After the tragic end of the Franco-Spanish expedition Chappe had led, some of the instruments remained in Mexico before being shipped back to Paris roughly a year later. The possibility of acquiring some of these instruments appealed to technically skilled local intellectuals such as José Antonio Alzate, whose letter to the Académie des Science is included in the English translation of Chappe’s Voyage to California. The desire to exchange European instruments and scientific legitimacy for local knowledge was a key motivation in communications between colonial settings and the imperial metropolis.

Know-how through the local press

The author of this guide to navigation wanted to give his audience in late-sixteenth-century New Spain the most up-to-date knowledge on navigational instruments. Theory and practice of celestial observation are supplemented with illustrations and a glossary at the end of the book. The book is an instrument in itself, one of the earliest of this genre printed in the Americas.

Textbooks: instruments for teaching and learning astronomy

para uso dos alumnos da Academia Real Militar. Digital version here.

Publishing activities were almost entirely forbidden in colonial Brazil, until the Portuguese royal family relocated to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 to flee from Napoleon's armies. The newly installed court catered to several long-held desires of the local elites, which included establishing libraries, institutions of learning, and printing presses. This fairly advanced textbook, a veritable instrument for teaching and learning astronomy, was one of the first books ever printed in Brazil.

The challenge of seeing, observing and correcting

la materia y formacion de las auroras boreales.

Digital version here.

Antonio de Léon y Gama was a polymath criollo who wrote on meteorology, astronomy, medicine and antiquities. In this dissertation on the aurora borealis, which was observed in central and northern Mexico in 1789, he clearly states his attitude towards experimentation: “Seeing is not the same as observing, however exact the instruments may be.” Léon y Gama's critical attitude towards correcting observations made with the assistance of technology reflects an awareness of the epistemic challenges surrounding instrumentation in New Spain.

The most useful instrument of all

harmoniosa mano. Digital version here.

Establishing the date of Easter is essential for defining the rest of the liturgical year – not to mention the civil year in early modern Christian societies across the Americas (and elsewhere). But Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the March equinox by liturgical definition, which is not necessarily straightforward to compute. So what if you are trying to figure out when Easter is going to happen in, say, 1760? According to the Astronomica, y harmoniosa mano, you simply use your own fingers. As the book reminds us, the most versatile instrument we have at our disposal is literally (in) our hands.

Acquiring and dispersing an American collection of European instruments and indigenous maps

Digital version here.

Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, author of this famous discursus on the nature of comets, collected European astronomical instruments, books, and indigenous maps. He obtained these objects through Flemish merchants, European missionaries, and his own personal contacts with members of the Mexica nobility. His will made clear that his mathematical and indigenous collections were to be bequeathed to the main Jesuit college in Mexico, but they were largely dispersed before and after they entered the Jesuit library.

Displaying foreign and local technology

Venus upon the sun. Digital version here.

Displaying adequate instrumentation was a challenge for American astronomers who wanted recognition in local and foreign scientific networks. In Providence and throughout New England, the 1769 transit of Venus was a good opportunity for proving local resourcefulness. West reported that, for this event, Moses Brown procured a three-foot reflecting telescope, a new micrometer, and a helioscope from instrument-makers in London. Lacking instructions, the group of New Englanders boasted that they had learned to use these instruments through trial-and-error and had also employed their own locally made tools.

Writing Histories

Studying the heavens, counting time and writing history seem to be indissociable elements. However, connecting the periodic movement of celestial bodies with the passage of human experience implies a certain set of beliefs and practices that are not innate to all cultures. For the Europeans that came to the Americas from the end of the fifteenth century, the Christian calendar, which observed liturgical festivities within solar and lunar cycles, was not only a time keeping instrument but the basis of history itself: the time of Creation and of Salvation were the beginning and end of human action; so history could only be told according to the astrological and astronomical frameworks that supported the Christian calendar. Since Amerindian cultures did not share this mode of time telling, the great challenge of colonial intellectuals was to find meeting points between Indigenous and European modes of computing time and memory keeping. The division between history – related to the recording of objective happenings in agreement with astronomical time – and myth – related to collective symbolic narratives and to other forms of time computation – was created in missionary and scientific writing. For creole intellectuals, discovering the history of their nation meant recovering – or recreating – the “astronomical” knowledge of the Ancients.

A Public Defense of Indigenous Astronomy for a National History of Peru

literatura, y noticias públicas. Digital version here.

The publisher of this erudite Peruvian periodical states that deciphering ancient history relies on scavenging scattered fragments from destroyed paper archives and silent living sources. This article on the “General Idea of the Monuments of Ancient Peru” aims to display some of these remains in public: by describing vestiges of stone monuments in Cuzco, he argues that the ancient Incas were skilled not only in technology and arts, but also in computational astronomy for agricultural predictions. Writing the scientific history of the nation strongly relied on recovering this astronomical past.

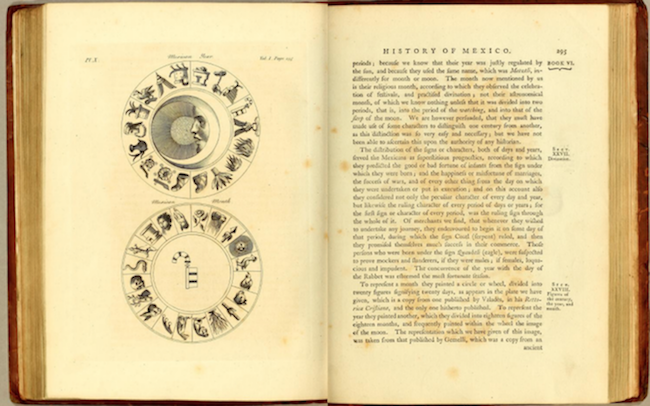

Inventing Lunar Months in Mexica Cosmology

Clavigero’s History of Mexico gives a compact narrative describing Mexica gods, cosmogonic stories, temples, and festivities. The Jesuit Clavigero states that this indigenous culture regulated time by lunar periods; with a new etymology for the word Metztli, moon, he creates an association between "moon" and "month". This reading represents a late-eighteenth-century project to assimilate Mexica notions of history and time to the idea of an "Indo-European astronomy". Drawn directly from the Italian first edition written by a Mexican Jesuit in exile, this English translation is testimony to the widespread interest in re-defining Mexican antiquities in Europe in the late eighteenth century.

The Myth of Columbus Foretelling a Lunar Eclipse

and entertaining voyages and travels. Digital version here.

The story that Columbus subdued the Arawak people of present-day Jamaica by correctly predicting the occurrence of a lunar eclipse in March 1504 was told by the admiral's first mythographer, his own son Ferdinand. This narrative, which uses astronomical prognostics as a means of domination, implied that Amerindians were not only ignorant of science but also of Christian time. Reproduced innumerable times in text and image, such as this late-eighteenth-century engraving included in Drake's collection of travel narratives, this theme also represents America’s introduction into European chronology.

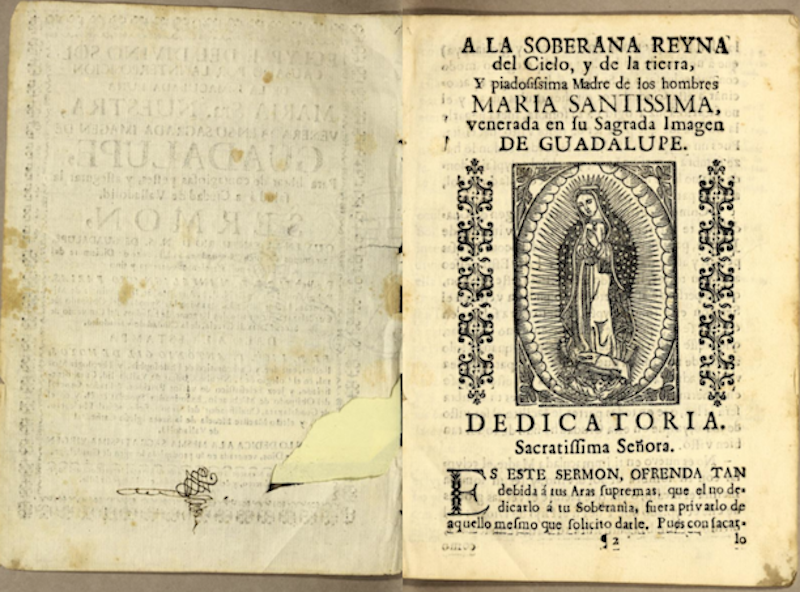

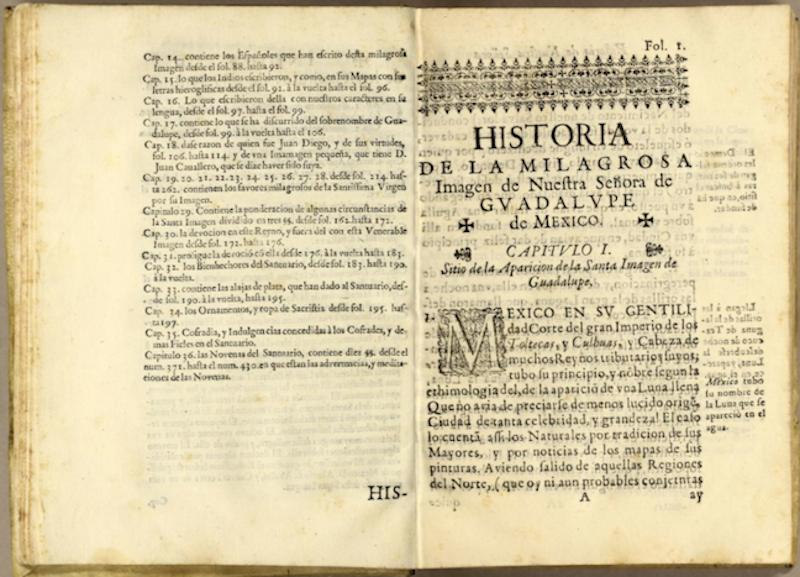

Resignifing the Foundation of Tenochtitlan

de Mexico. Digital version here.

This late-seventeenth-century history of the Virgin of Guadalupe begins with the foundation of Tenochtítlan. Florencia recalls that as the Mexica wanderers reached the lake of Tezcuco, the dark sky suddenly cleared up and a crescent moon was perfectly reflected in the water, like a celestial picture. Again according to Florencia, the image was taken as an omen and, the following day, the Mexica people found the symbol of their promised land: an island with an eagle perched on a cactus devouring a snake. This story associates the indigenous origin chronicle with the Moon, a representation of the Virgin Mary in Christian iconography. With this opening, Florencia sets out to create a Christian history of Mexico by arguing a pre-conquest presence of the Virgin of Guadalupe in that land.

Geological History vs Cosmological Time in New Granada

Humboldt argues that Amerindian stories of the cosmos were shaped by the experience of geological changes over time. In his description of the Tequendama Falls in present-day Colombia, he tells a Muysca story drawn from the 1688 General History of the Conquest of the New Kingdom of Granada by Lucas Fernández Piedrahita: a benevolent bearded old man comes with his wife to the wild Valley of Bogotá bringing clothing, a dwelling, and agriculture to the local inhabitants. His evil wife then provokes a calamitous flood. As she is punished and cast away by her husband, she becomes the moon. The old man then breaks down the mountains surrounding the flooded valley, saves its inhabitants and institutes solar rituals amongst the Muyscas. Finding common traits between this story and other narratives in Asia and Arcadia, Humboldt attempts to reconstruct a general universal theory of cosmologies that were not based on what he considered to be scientific practices.

Writing the Divide between Astronomy and Superstition

d'un voyage dans l'Amerique Méridionale. Digital version here.

In the diary of his journey down the Rio Marañón in 1743, French astronomer La Condamine narrated his encounter with a multitude of Amazonian communities he encountered along the river. Wishing to compose a story of the language and beliefs of the Omagua people, he associated the name of the tribe, meaning “full moon”, with the ritual of flattening infants’ heads with planks to resemble the full moon. La Condamine observed and reported on the importance of celestial understanding in Amazonian cultures, but did not relate them in any way to his own. While his travel writing was likened for centuries to objective note-taking, close study shows his stereotypical eighteenth-century ideas about the separation between "scientific" and other culturally dependent forms of knowledge.

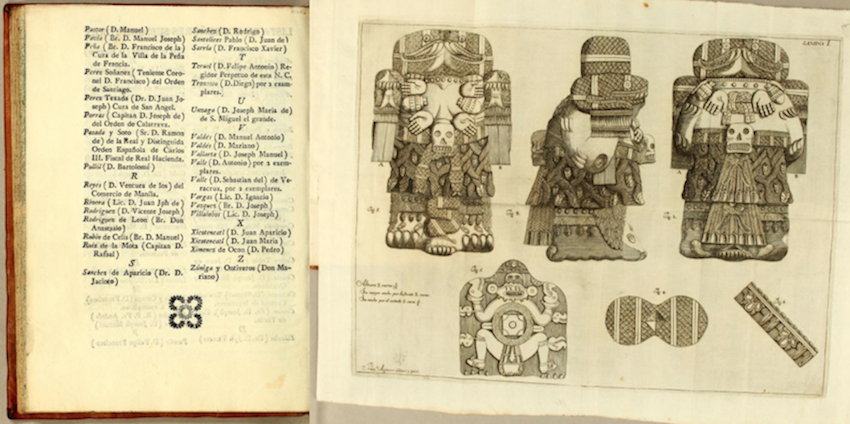

Reading Antiquities and Reinventing the Calendar

cronológica de las dos piedras. Digital version here.

In 1790, two imposing Mexica monuments unearthed during urban renovations of the central plaza of Mexico City gave way to antiquarian discussions about astronomical time in Mexica culture. The stones were read, interpreted, and explained by Antonio de León y Gama, a Mexican criollo intellectual, to be chronological and calendrical documents that proved the ancient nation's advancement in astronomical observation. This indigenous knowledge, he claimed, had degenerated in post-colonial times, as it had been silenced by the indigenous intellectuals who wanted to protect themselves against accusations of idolatry.

Exiled from Christian Time in France Antarctique

autrement dite Amerique. Digital version here.

In the dramatic narrative of his experiences in colonial Brazil, Jean de Léry lamented that the Tupinamba people were ignorant of the periods constituting Creation and Salvation. Even though they counted time by lunar observation – and, thus, shared certain elements with the Christian calendar – they appeared to Léry to live outside of Christian time. As a Protestant and an anti-colonialist, and with more than a whiff of nostalgia, Léry depicted the image of the predestined savage looking vainly at the skies.

The history of the Americas within the order of the cosmos

Nueua Espana. Digital version here.

After discussing the workings of the celestial spheres and giving lunar prognostics from 1606 to 1620, the Royal cosmographer of New Spain, Enrico Martinez, shifted his attention to the four elements (fire, air, water and earth) and turned from telling the future towards a reconstruction of the American past. His theory is that the first inhabitants of the continent came by land and not by sea. He reports having seen people physically similar to the Indigenous peoples of New Spain in a European province called Curlant (which was subject to Poland), and who who may have crossed into the Americas through the northern strait of Anian. He also surmises the possibility of a similar movement from the southern pole, then considered to be terra nullius, or a land yet unknown. Thus begins a narration of the history and decline of the Mexica Empire.

Biblical History and Astrological Disposition

de los indios occidentales del Piru. Digital version here.

Echoing theories about the geographical distribution of race after the Deluge, Rocha argues that Amerindians are decedents of Tubal, a grandson of Noah who populated Spain, and whose people traversed the Atlantic. To make his claim, amongst many arguments, he states that ancient Spaniards and Amerindians shared common traits such as idolatry, ignorance of science, and brave temperament. This dissertation and the appended letter about the comet of 1680 share a biblical and astrological framework for the writing of history.

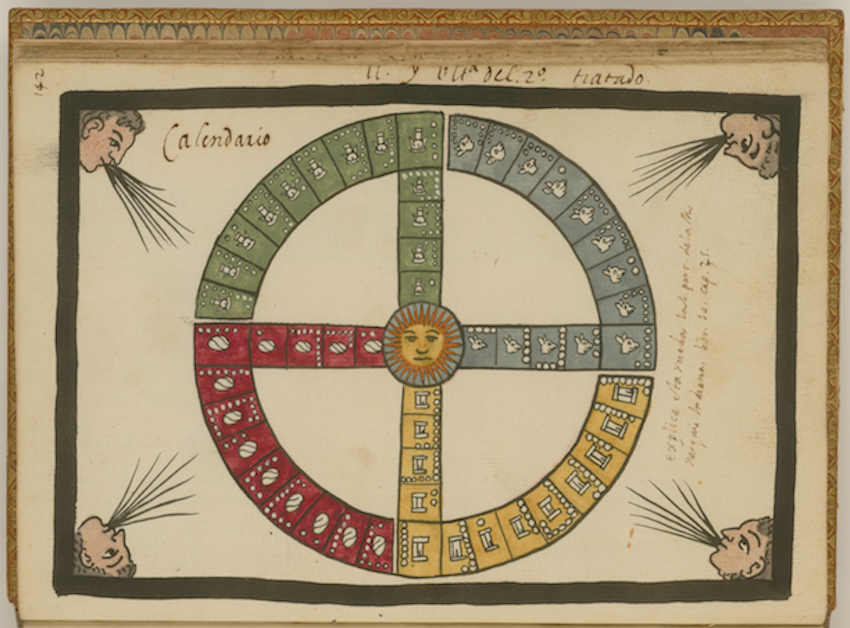

Writing a Chronicle on a Reimagined Calendar

This indigenous manuscript is an incredible artifact of time re-elaboration. The Jesuit Juan de Tovar commissioned indigenous artists to make a calendar capable of expressing Christian liturgical festivities and the Nahua cycles of twenty days, understood by Europeans as months, in a single legible space. The format of the codex resembles an almanac, with one page per month, but instead of predicting the future, this calendar is a chronicle about the past of the Mexica people. Notice here the signs of the zodiac and names of the months in Latin alongside what is clearly an indigenous pictorial language.

Instruments of Conversion

The conversion of Indigenous peoples to Christianity was the ultimate ideological justification of the European invasion and colonization of the New World. Missionary activity in the early Americas not only shaped colonial societies and territories in every conceivable way, but was also directly linked to a process of world-historical importance such as the rise of the transatlantic slave trade. In their day-to-day work, Christian missionaries across the Americas resorted to their privileged knowledge of Indigenous languages and frequently employed astronomical references in order to access Indigenous people's belief systems, as some of the materials displayed in this constellation demonstrate. Conversion was not limited, however, to gaining new souls for the Christian faith, but it also meant policing the behavior and beliefs of large populations of European ancestry, who were already among the faithful. For this end, preachers and religious authors made use of remarkable celestial phenomena to inspire reverence, or to claim that the stars revealed some kind of special divine protection for the Americas.

"They worship the sun"

Digital version here.

Inspired by their Asian experience, the Jesuits turned to fighting "idolatry" as their central hope for the conversion of Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Acosta, one the main architects of this missionary strategy, dedicated several pages of his influential book to a description of what he saw as idolatrous practices of the Andean peoples, who were particularly prone to missionary intervention. Many of these practices had a cosmological nature, entangling earth and skies, and Acosta hoped that missionaries could take advantage of their own astronomical knowledge to counter these "idolatrous" engagements.

How to ask if a comet is a bad omen in Aymara

This grammar and phrase-book of the Aymara language, printed by the Jesuit missionaries at Juli, on the shores of Lake Titicaca, contains numerous examples of phrases that missionaries could use in order to identify Indigenous peoples' idolatrous practices, including their beliefs about the stars. On this page, a missionary could learn how to inquire as to whether an Aymara-speaker believed that a comet was a bad omen.

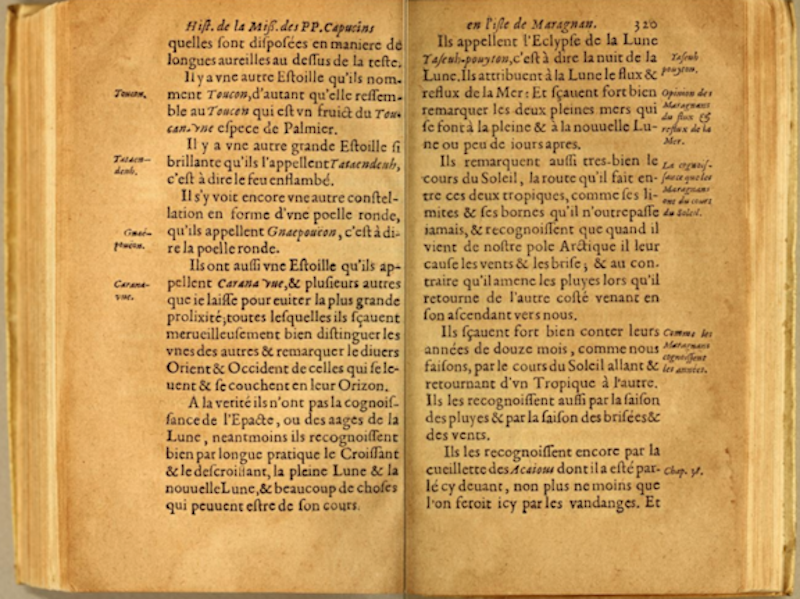

A French missionary describes the celestial knowledge of the Tupinamba

capucins en l'isle de Maragnan. Digital version here.

During their brief colonial experiment in Northern Brazil, the French made an alliance with the Tupinamba people, who were interested in repelling the Portuguese. Colonial settlement took its legitimacy and justifying force from missionary activity, in this case led by Capuchin friars like d'Abbeville. His book, a chronicle of the "spiritual conquest" of the Tupinamba, contains references to their sky-lore. This page contains a discussion of Tupinamba constellations and star names, their knowledge of lunar eclipses, the relation between tides and the moon, and the annual motion of the sun around the celestial sphere.

The moon, mother of God, protects the faithful from the plague

This sermon brings together astrology and religious emblematics. The moon, mother of God, represents the shadow covering the Sun during a solar eclipse. By doing so, she protects the inhabitants of Valladolid (Mexico) – who observe the eclipse from a privileged location – from Christ's divine justice and therefore frees the Spanish city from the plague of Matlazahuac. Farías emphasizes that regions north and south of Valladolid, inhabited by “Chichimecas”, were not granted the same protection.

Etymology of place-names in the service of faith

Digital version here.

This history of the appearances of the Virgin of Guadalupe was written by a criollo Jesuit born in Florida who played a key role in late-seventeenth-century Jesuit politics, both in Europe and in the West Indies. At the beginning of his work, Francisco de Florencia gives his etymology of Mexico. Associating Metztli – moon in Nahua – to Metzico, he resignifies elements of the Mexica foundation narrative as premonitions of the presence of the Virgin of Guadalupe in the same territory.

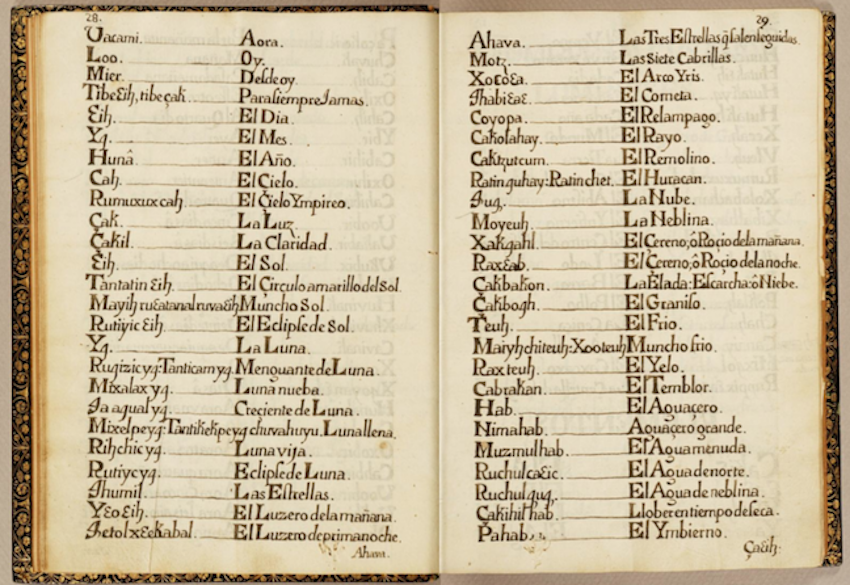

A missionary vocabulary from central Guatemala

cakchiquel. : Año D. 1704. Digital version here.

Guzmán was vicar of the Indigenous parish of Santa María de Jesús in Sacatepéquez, present-day Guatemala. This vocabulary of the Mayan Kaqchikel language, which Guzmán finished compiling in late 1704, is thematically arranged for ease of use by other missionaries. The pages shown here come from a section dealing with celestial bodies, time, weather, and the elements, the knowledge of which was deemed useful for the work of conversion.

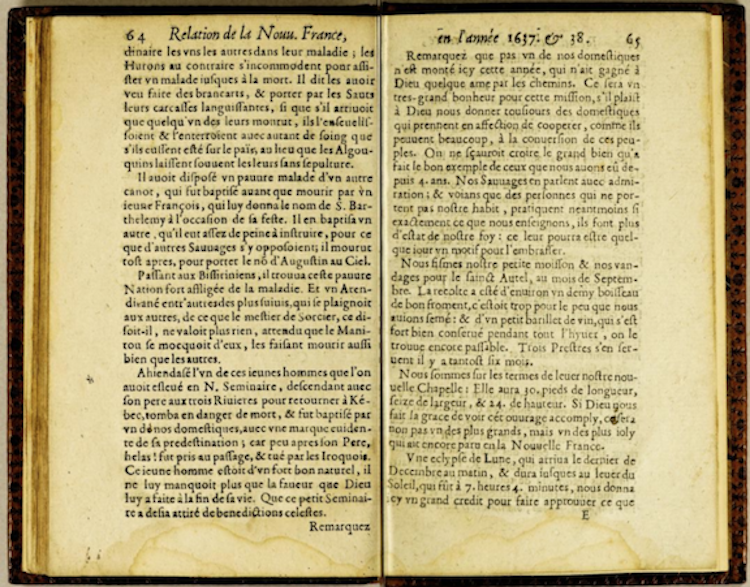

A Jesuit claims that astronomical knowledge facilitates conversion

pays des Hurons és années 1637. & 1638. Digital version here.

The prediction of an eclipse as a means for inspiring awe in non-European peoples is a familiar topic in early modern missionary literature, among other genres. In this example, a Jesuit tells his superiors how one such successful prediction earned him the respect and facilitated the conversion of some Huron communities in present-day Canada. Upon reading such narratives, many college-trained European youths thought that astronomical knowledge could open the doors to a missionary life in the Americas or Asia.

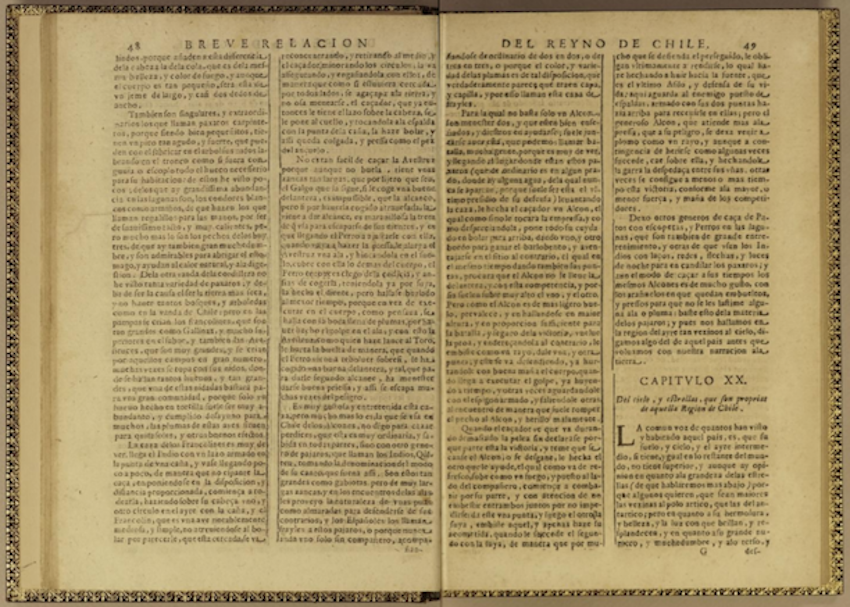

The cross for the southern skies of Chile

de Chile. Digital version here.

Ovalle, a Jesuit born in Chile, included a textual and visual description of the southern skies in this providential history of his native territory. He wrote the book during his commission as a Provincial in Rome, and published Spanish and Italian editions the same year in order to promote the Chilean mission. Among the southern constellations, Ovalle highlights the shape of the cross in order to claim the American skies for Catholicism.

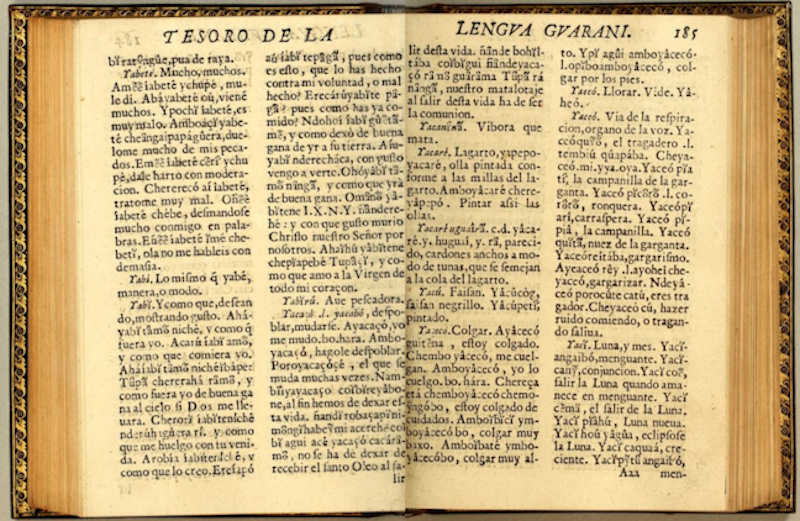

"I will come back in two moons"

Digital version here.

The Peruvian Ruiz de Montoya was a founder of the very important mission of the Guayrá, on the present-day border between Paraguay and Brazil. As did many Jesuit missionaries, he placed great value on mastering the languages spoken by the people he intended to convert - in this case, Guaraní. On the lower right of this double-paged spread, one can see the beginning of the entry for yacy, "moon," which contains several phrases that would have been useful to missionaries, such as the Guaraní for "I will come back in two moons [i.e. two months]."

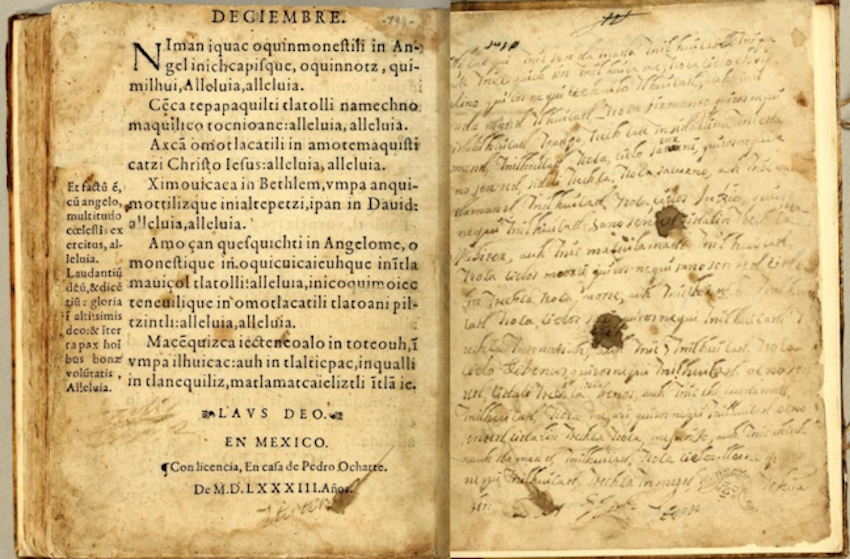

A Nahua student tries to make sense of Christianity through cosmology

Digital version here.

This book is a towering monument of indigenous Nahua scholarship, for Sahagún is only one of a number of authors of this collection of psalms in Nahuatl. In reality, the work included the participation of a large number of Indigenous intellectuals. But what does it have to do with astronomy? That connection appears in a most poignant way on the very last folio: the manuscript annotations, in Nahuatl, recount the order of the celestial bodies – from the firmament down to the moon – and explain that the heavens are made of crystalline spheres. In other words, this Nahua learner realized that in order to make sense of Christian religion, he had to understand Christian cosmology.

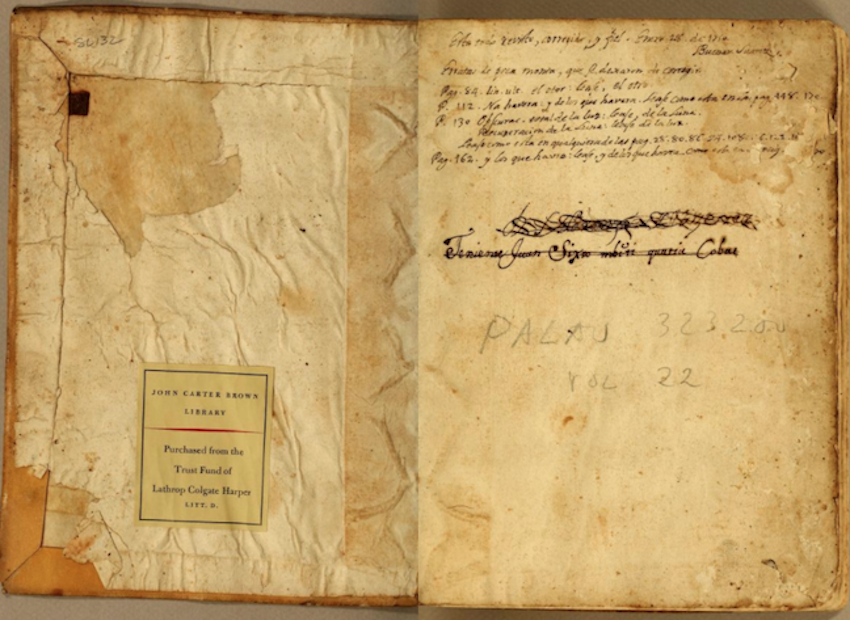

A Guaraní official and a Jesuit astronomer

Suárez, a Jesuit priest born and educated in Argentina, spent most of his life as a missionary in the Jesuit reductions, where he wrote this Lunario. This particular copy is a moving testament to the social structure in what would become the largest Jesuit mission in history (which was wiped out during the Guaraní Wars of the mid-eighteenth century). The book belonged first to Suárez and then to Juan Sixto Mbiti, the Guaraní deputy corregidor of the village of San Lorenzo Mártir, in present-day Brazil.

Translating Nahua into Christian time

Finding the connections between the Christian liturgical calendar and indigenous systems of time computation, the latter of which were not necessarily astronomically based, was one of the main concerns of missionary intellectuals. The appendix to the Jesuit Juan de Tovar's codex, made by an indigenous hand, is considered the most successful attempt at this translation enterprise in the sixteenth century. Tovar replaces native Nahua signs with Christian Dominical letters.

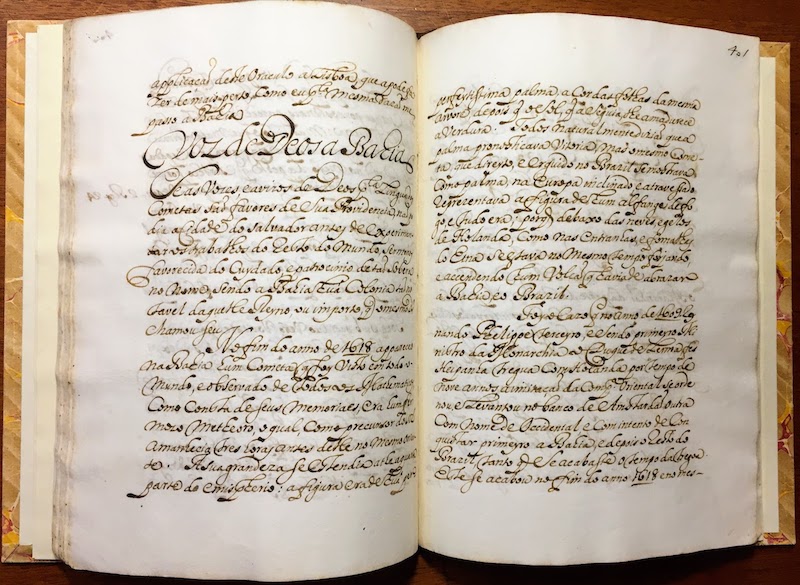

"Look, oh Bahia, at the skies"

Conversion can be understood not only as adopting a new faith, but also as the permanent renewal of an already professed faith. Self-examination and the admission of being a sinner are two of the main instruments for accomplishing this ideal, as is the sacrament of confession (among Catholics). In this sermon, António Vieira takes advantage of the appearance of a comet in the skies of Salvador to admonish the faithful: "Look, oh Bahia, at the skies, and at yourself, and see if inside your houses, and outside of them (...) there exist concealed or public sins (...) of which you will find plenty and grievous."

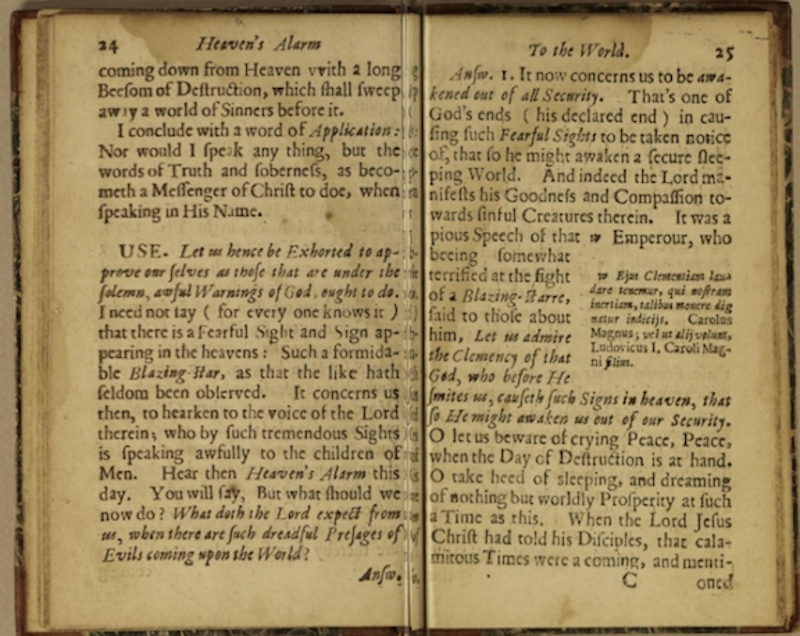

"What doth the Lord expect from us"

Christian clergymen across the early Americas, on both sides of the Catholic-Protestant divide, seldom lost an opportunity to use the appearance of comets, as well as other relatively rare, wondrous celestial phenomena, to teach moral lessons to their congregations. In a world suffused with evil and temptation, the faithful had to be permanently vigilant of their own ways, and God reminded them to do just that by sending signs. This is one of two sermons preached by Increase Mather in Boston, in the early 1680s, taking advantage of two comets that were sighted within a short interval of one another.

Related Events

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

There are no events to display currently. Please check back soon.

Credits

Digitization of items for this exhibition has been generously supported by the R. David Parsons Fund for Digital Exploration. Programming support was received from Robert N. Gordon (in memoriam) and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Curators: Nydia Pineda (University of California, San Diego) and Thomás Haddad (Universidade de São Paulo)

Specialist Consultants:

Laura Bland (University of Houston) - Seventeenth century comet tracts

Guillaume Candela (Center for the Study of the Early Modern World, Brown University) - Tupí-Guaraní language materials

Ana Díaz (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) - Nahuatl language materials

Virginia Iommi (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile) - Celestial images

Antonio Neme Castillo (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) - Data visualization and analysis

Andrés Vélez Posada (Universidad EAFIT, Colombia) - Early modern cosmography

Artistic Contributor and Consultant:

Ale de la Puente (Sistema Nacional de Creadores, México)

Website Administration:

Tara Kingsley

Video Production:

Sabrina Almandoz

Hugo Magaña

Lalo Santoyo