Early Mexican Imprints at the JCB

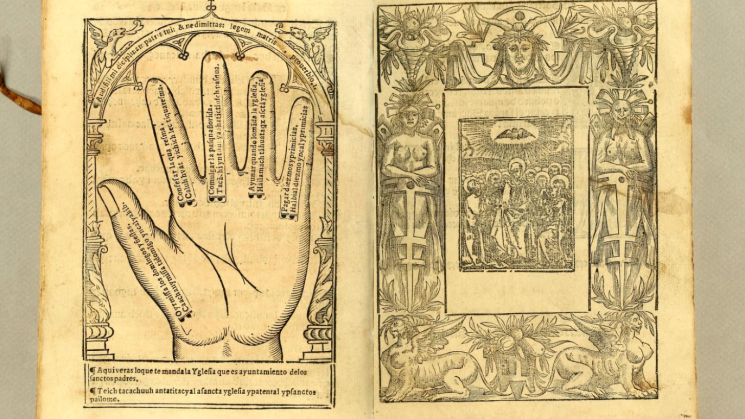

The JCB collection boasts an extraordinarily rich subset: the earliest products of the printing press in the Americas. These 16th-century Mexican imprints offer a window into a tumultuous era, revealing violent political and religious transformations, complex epistemic exchanges, diverse linguistic landscapes, the educational aspirations of elites, and emerging legal frameworks.

Last summer, I spent two weeks studying the 66 early Mexican imprints preserved in the JCB. Published from 1544 to 1600, these works represent the cradle period of the printing press in New Spain. They make up a multilingual collection written in two European languages, Spanish and Latin, and five Amerindian languages: Náhuatl, Purépecha, Zapotec, Huastec or Tének, and Tzotzil.

Religious titles comprise the majority of this corpus (42 titles). These books were crucial aids in spreading Christianity and replacing the Indigenous world vision and religious beliefs. They range from primers and short catechetical works for beginners to more sophisticated presentations of Christian doctrine, including sermons, confession manuals, and chants. These materials were intended to incorporate both the doctrinal and liturgical practices of the new religion.

While religious works dominated, the collection also includes a diverse range of secular texts. A significant subgroup consists of textbooks for higher education, printed to introduce students of the Royal University and other schools to subjects like Latin, Logic, Physics, Cosmography, and Theology. Other subjects include medical treatises and legal compilations. The collection's diversity is further demonstrated by works on specialized topics such as naval engineering, military strategy, and even a decree announcing a new sales tax. These non-religious texts offer valuable insights into the educational priorities and administrative concerns of colonial New Spain.

The printing press played a crucial role in codifying Indigenous languages, a process that served both missionary and administrative purposes. The JCB’s collection of sixteenth-century linguistic works are aids in the study of three widely spoken languages: Náhuatl, the lingua franca of New Spain in the 16th century; Purépecha (also known as Tarasco), the language of the kingdom of Michoacán; and Zapotec, spoken in the region of Oaxaca. Fray Maturino Gilberti, a Franciscan expert in the language of Michoacán, offered the grammatical rules “through which Spaniards can easily learn the language of the Indians and the Indians the language of the Spaniards.”

Imagining these books as tangible objects—handled and cherished by real people—reveals much about the relationship between readers and texts in 16th-century New Spain. Were they intended to be read aloud, shared with Indigenous communities, studied in depth, or incorporated into rituals? Marginal annotations offer glimpses into individual readers’ thoughts, while fire brands and ex libris stamps trace ownership histories. Questions abound: How did Indigenous people contribute to book production? What anxieties and priorities of civil and religious authorities emerge from preliminary pages? Our collection of early Mexican imprints is more than a repository of texts—it is a catalyst for ongoing inquiry into the complex cultural landscape of colonial Mexico.

January 15, 2023. Updated September 12, 2024

*I have added a blog entry devoted to early Peruvian imprints in the JCB collection.