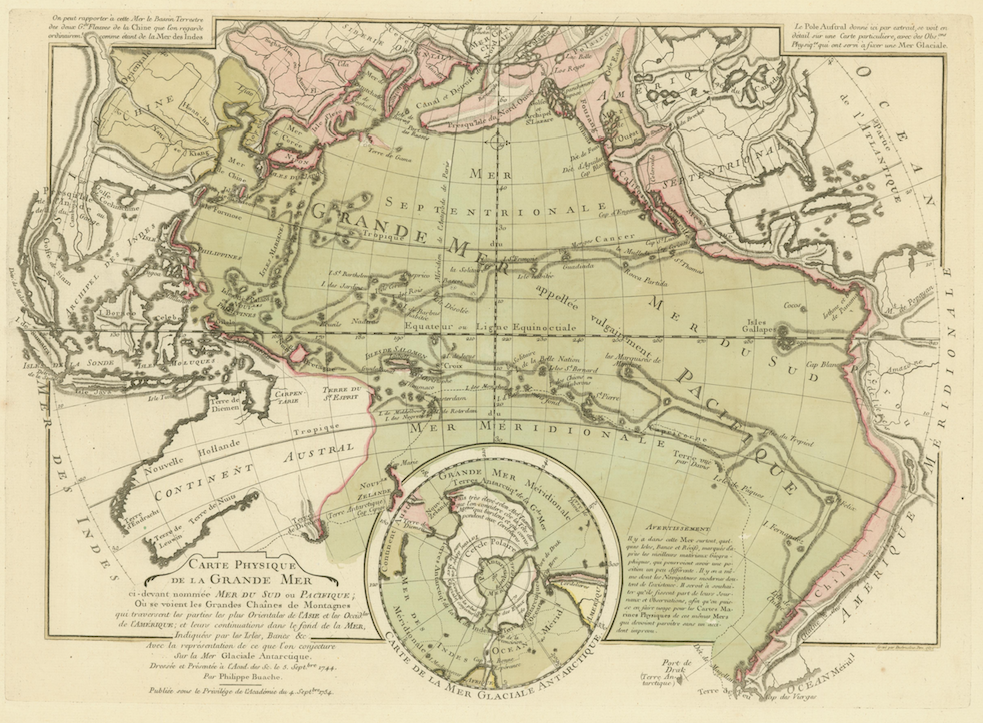

Philippe Buache, “Carte Physique de la Grande Mer ci-devant nommée Mer du Sud ou Pacifique…” from Cartes et tables de la géographie physique ou naturelle: présentées au roi le 15 mai 1757, Paris: 1770

Philippe Buache was a member of the Delisle-Buache succession of French cartographers that straddled the eighteenth century, and, as of 1729, was the premier géographe du roi, following in the footsteps of his father-in-law Guillaume Delisle. While his cartographic output didn’t rival that of Delisle’s, Buache can be credited with producing extraordinarily creative and innovative maps based on theories of geology, geography and bathymetry – the mapping of the depth of water in oceans, rivers and channels – that he developed over the course of his career.

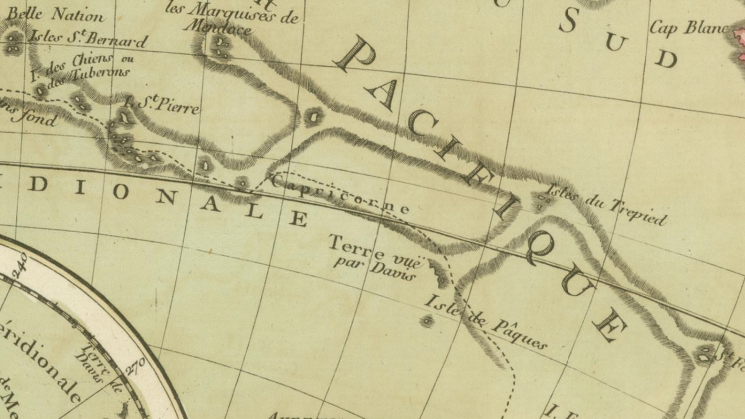

This month’s map, Buache’s “Carte Physique de la Grande Mer ci-devant nommée Mer du Sud ou Pacifique…” was published in what can be considered the first thematic atlas, entitled Cartes et tables de la géographie physique ou naturelle: présentées au roi le 15 mai 1757, of which the JCB owns a 1770 edition. This map, of the Pacific Ocean, is the first attempt to map the bottom of any ocean, and it is a one is a series of similar maps that Buache created over a space of several decades; indeed, he first experimented with cartographically depicting the depth of water with lines, now called isobaths, in a manuscript map of the floor of the English Channel that he presented to the Académie des sciences in 1737 (the map was published 1752).

In the “Carte Physique de la Grande Mer…,” Buache drew on his idea that the geological features evident on the landforms of continents, such as mountain ranges and valleys, existed in a relationship with similar features under the ocean, and he used the soundings that mariners had begun marking on charts in the mid-sixteenth century as both evidence and a source of data. Amongst other features, this map therefore shows the connections between two mountain chains, now known as the Andes in South America and the Rockies in North America, and geological formations in the Pacific Ocean. (Note, too, the fantastical ‘Mer de l’Ouest’ in western Canada, a feature that dogged Buache’s mapmaking.) By extension, Buache shows on this map, continents were connected to islands located at great distances from them. The reliability of his data ultimately undercut his ability to convince his contemporaries of the larger arguments he was making. Nevertheless, Buache’s ability to imagine anew the oceans and surrounding landforms, and to cartographically inscribe them in an altered set of relationships marks a pivotal shift in the histories of cartography and Enlightenment science.

Explore the map:

You can close the 'media information' panel and zoom in to see the map in full.